In Karl Ove Knausgaard’s novel A Time for Everything, the narrator says that if we are to understand his character, a sixteenth-century Italian named Antinous, it won’t come from charting the inner landscape of his life. “Antinous was, first and foremost, of his time, and to understand who he was, that is what must be mapped.” Our tendency to interpret all external events by the way they shape the dark crevasses of the psyche is a modern one, he asserts, a paradigm ushered in by Freud, and it would be a fatal mistake to presume that people back then were anything like us, that their thoughts and feelings were shaded by a common consciousness, since “our world is only one of many possible worlds.”

This approach to literature might seem antithetical to Knausgaard’s more famous project, his six-volume autobiographical novel My Struggle, the fifth installment of which has now been translated into English. My Struggle is best known for its obsessive devotion to one life, the intimate rendering of the quotidian events that mold it, and the tacit proposal that the universe, in its entirety, is but what passes through the prism of a single being. Toward the end of Book Three, which is devoted to his childhood, Knausgaard awakes in a hospital after a fainting spell to the sound of Roxy Music playing in the distance. The song’s lyrics—“More than this / There is nothing”—combine with the “pale, bluish summer night” to produce in him a feeling of elation. The lyrics are, in the most direct sense, about life’s finitude, suffused here with the euphoria that accompanies convalescence. But in another sense they spell out a dominant theme in Knausgaard’s work—that there is nothing more than this sky, this song, this moment, this awareness of ourselves in the world.

The idea that the world is confined to our senses, that it dies when we die, has a long history, finding its fullest expression in Knausgaard’s principal inspiration, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. In it, the character Bergotte, dying before Vermeer’s 1662 painting View of Delft, regrets that his writing was unable to match the vivid intensity of the painting’s “little patch of yellow wall,” a scene that speaks to Proust’s own emphasis on meticulously recreating subjective experience so that it remains forever fixed beyond the earthly ravages of time. But even Proust did much more than embellish his patch of wall, weaving historical elements such as the Dreyfus affair and the intricate hierarchies of the Faubourg Saint-Germain into his novel about perception and memory.

In contrast, across the first four books of My Struggle, contemporary Norway has been notably absent. There’s an opaque comment about immigration here, a reference to the country’s oil economy there, scattered between hundreds and hundreds of pages devoted to 1980s indie rock, drunken mishaps, sexual yearnings, an emotionally abusive father, the finer details of parenting, and, above all, the great struggle to make art. Knausgaard’s resistance to a grand novelistic architecture, and his refusal to be tyrannized by topicality, are partly what make his book so attractive. But a diary, no matter how compelling, is not a novel; and a life, no matter how rich, is not autonomous from the backdrop against which it is set. It is in Book Five that Knausgaard’s epoch finally heaves into view, providing his granular foregrounding with its context. It is here that we get a fuller sense of this one of many possible worlds.

That My Struggle is actually a commentary on contemporary life in the West, a sweeping novel of ideas in the tradition of Thomas Mann and Fyodor Dostoevsky, is foreshadowed in the title, which links the modest travails of one man on the northern periphery of the European continent to the preeminent historical figure of the twentieth century. But its ambition has always been belied by what amounts to Knausgaard’s philosophy about literature, which is that whatever truth the novelist has to convey comes not from ideas, but from emotions. “The heart is never wrong,” he writes in Book Five. Everything stems from what he has felt, what he has experienced in its utmost immediacy, as if to say there is greater truth nestled in the black folds of jealousy than in the work of Karl Marx or Immanuel Kant. There are certainly no flamboyantly verbose characters, à la Mann’s The Magic Mountain or Dostoevsky’s Demons, who stand for schools of thought and political theories. If we are to have ideas, they will have to flow through the radically narrow perspective that Knausgaard has established, floating alongside the rest of life’s flotsam: all those cigarettes smoked, all those feelings hurt, all those books read.

In this respect, Book Five is like the ones that preceded it, the next chapter in a more or less chronological progression that began with Book Three (boyhood) and continued with Book Four (adolescence). It tracks, over some 600 pages, his time in the university town of Bergen, from 1988 to 2002, a period that begins with him entering a prestigious writing program as a precocious 19-year-old. But the straight track to a glittering career is not to be his, and the trajectory of his young adulthood, like those of most twenty-somethings, is more like an aimless loop than an arrow’s flight. Over the course of 14 years, he hangs out with his brother and goes to many parties, clubs, and bars. He gets into his first serious romantic relationship, then cheats on his girlfriend during one of an endless series of alcoholic binges. He tries and fails to write poetry, tries and fails to write fiction, and plays in a band. He ekes out a living by stringing together various gigs, at an institution for the disabled, a radio station, an oil rig. He meets a woman who will become his wife, goes on more binges in which he steals bikes and cuts his face, writes some book reviews, cheats on his wife, and ends their marriage. Amidst all this, he also, somehow, writes and publishes his first novel.

This may make it sound like Book Five ends on a triumphant note. It certainly contains one of the truest depictions of how a novelist comes into being, how he emerges, alongside his creation, from a shapelessness that is empty of everything but the desire to write. But Book Five is easily the saddest volume thus far of My Struggle, and his literary debut is not enough to redeem the misery that stalks him at every turn. If the novel is a kind of salvation, pulling him out of a spiral of self-destruction, it is also a curse, since his monkish devotion to the book is one of the reasons his marriage falls apart.

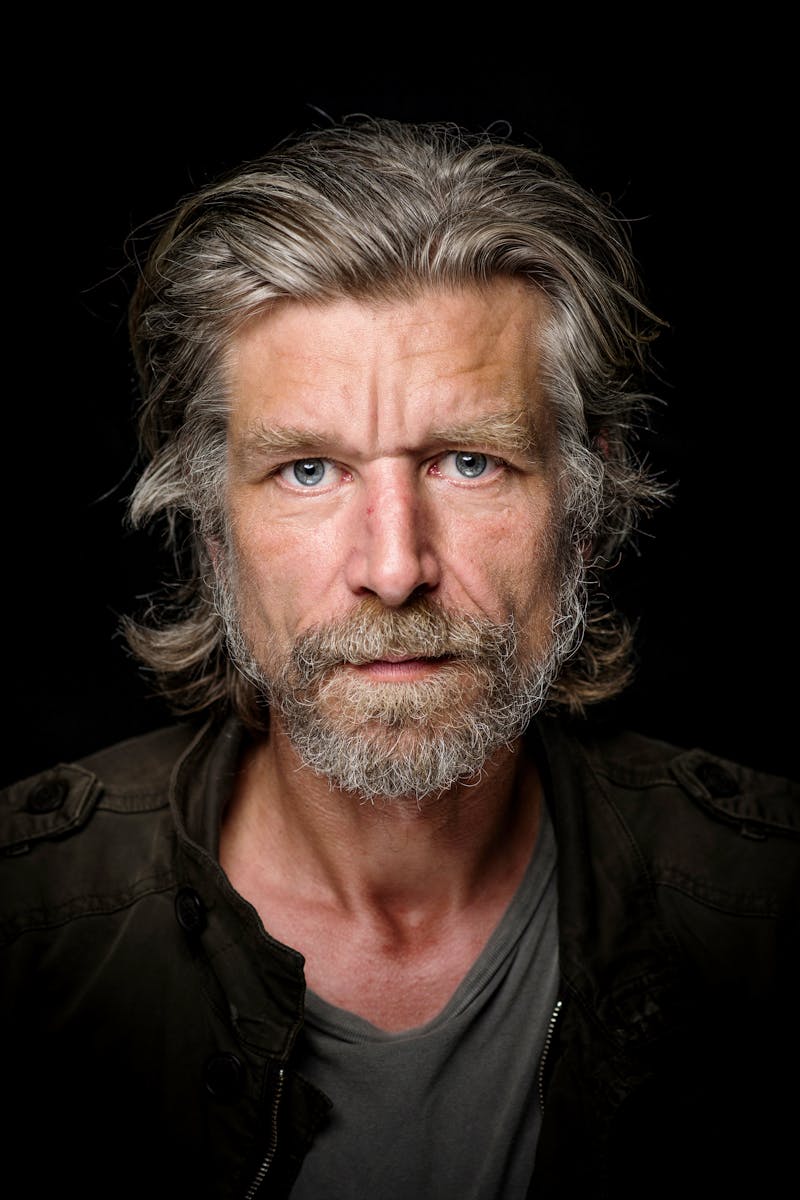

Why is Karl Ove Knausgaard so damn sad? In many ways, this is the question that animates My Struggle. “I was 40 years old when I started to write this book,” he told Charlie Rose in 2015. “I had three beautiful children, I had a beautiful wife, I had, you know, a house, it was like the Talking Heads song, I had all this, but I wasn’t happy.” The proximate cause of his unhappiness is his inability to write. In Book One, it is “the ambition to write something exceptional one day” that gnaws at him, that turns time into a nemesis, and that makes his life at home, filled with distracting chores and obligations, an existential threat. In Book Five, from the perspective of a young man who has written virtually nothing and is unsure of his powers, the case is more dire: “Writing was a defeat, it was a humiliation, it was coming face to face with yourself and seeing you weren’t good enough.”

But the desperate need to write is but a proxy war for a bigger battle, one that pits Knausgaard against the ancient antagonists: death and its spawn, absurdity. If life is but a cosmic joke, and our ambitions are made vain by the great oblivion that awaits us, then art is everything life isn’t: coherent, meaningful, timeless. More than that, the creative act is a rare source of dignity, in that it is a dogged defiance of fate that is simultaneously aware of the futility of that defiance. As Camus once wrote, “Perhaps the great work of art has less importance in itself than in the ordeal it demands of a man and the opportunity it provides him of overcoming his phantoms and approaching a little closer to his naked reality.” This is an apt description of Knausgaard’s project, where reality is very much presented in its naked absurdity, as a series of events that all tumble together in an immense outpouring, equal under an indifferent sky: a tea kettle boiling on the stove, words scrawled across the page, planes flying into the Twin Towers.

For much of Book Five, however, Knausgaard is without the ballast of his art. He has the vocation, but the blank page is a wall. And so his awful fate engulfs him: “I got dressed and went downstairs, death, out of the door, death, up the hill, death, through the underpass, death, down the road, death, along the fjord, death, and into the park which wrapped itself around me with its living yet sleeping darkness.” This passage occurs shortly before his first act of adultery, which is in keeping with how the book presents sex and alcohol as means of transcendent escape, blissful bursts of torrid flight that invariably result in Knausgaard falling back down to earth. Naturally, for a novel steeped in realism, the crash manifests itself as a hangover, which in Knausgaard’s hands constitutes a private hell of lacerating regret and shame, the modern everyman’s version of the punishment that follows Raskolnikov’s crime in Dostoevsky’s novel.

There is something, too, of Raskolnikov’s restless desire to soar above the gray mass of humanity in the young Knausgaard’s bouts of deranged drunkenness. “I was going to be a writer, a star, a beacon for others,” he writes early on, only to be confronted by a failure so devastating that he is left grasping for the “feeling of triumph” produced by alcohol. At one point, a drunk Knausgaard, swollen with self-importance, thinks to himself, “Jesus, man, I was somebody, I could see something no one else could see, I could see into the depths of the world.” Knausgaard at his most triumphant is, like all drunks, both pathetic and frightening, transgressing laws and the basic rules of decency to prove that he is above them. He slips into unlocked cars and tries to jumpstart them. He picks fights with his brother’s friends for no reason. He stalks women he’d like to sleep with, throwing stones at their windows in the dead of night. And in a reprise of a disturbing incident in Book Two, he slashes his face up with the shard of a broken beer glass, to the horror of the woman who will become his wife. It is here, in this violation against the self, that transgression and transcendence combine to produce a hideous deformation of art’s promise to pull us out of ourselves. It is reminiscent of what Knausgaard’s countryman Stig Sæterbakken, himself a suicide, once wrote in a revealing essay: “It’s the prayer we direct toward any great work of art: God, take this pain away, which is me.”

In the summer of 2012, a psychiatrist named Ulrik Fredrik Malt testified at the trial of Anders Behring Breivik, who a year earlier had killed 77 people—most of them teenagers—by detonating a bomb in Oslo and going on a shooting spree on the island of Utøya. As recounted in One of Us, journalist Åsne Seierstad’s 2015 account of the massacre, Malt said of Breivik, “His personality and extreme right-wing ideology are combined in an effort to get out of his own prison. He ends up ruining not only his own life but that of many others.” It is not hard to make the connection between the extremist—with his taste for violence, his penchant for self-aggrandizement, his will to power, and his desire to be borne aloft on a triumphant swell of emotion—and Knausgaard’s demon within. The poisonous seed in each of them flourishes in the same airless environment, one that is moted by failure and hopelessness. It is also not hard to see the link between Knausgaard and Adolf Hitler, who famously started his adult life with aspirations to be a great artist.

What is difficult to determine—the question that lies at the heart of Book Five—is the correlation between modern Norway and the kind of social and economic ferment that led to Hitler’s rise. Nearly the entirety of My Struggle is set in what amounts to paradise on earth. Ever since the discovery of vast reservoirs of oil in the North Sea in 1969, Norway has been flush with cash, which in turn has been wisely invested in creating one of the strongest welfare states in the world. As so many American liberals are fond of pointing out, poverty is virtually non-existent in the Nordic countries. Norway’s state-driven approach to capitalism has ensured that everyone’s basic needs—and much, much more, from generous child care to education—are essentially taken care of. Seierstad notes that at the height of the financial crisis, thanks to a robust response from the government, Norway’s unemployment rate rose no higher than a little over 3 percent. This is a country that, by all outward appearances, is competent, confident, and thriving. As then-Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland declared in 1994, bolstered by the success of the Olympic Games in Lillehammer, “It’s typically Norwegian to be good at things.”

And yet Knausgaard can plausibly liken himself to a character from the fevered writings of Dostoevsky, “the impoverished young student in the metropolis.” It is as if the fundamental spiritual illness of the modern era—a ubiquitous anomie brought on by the collapse of communal identity and the death of religion—has not abated at all over the many decades, even in a country where social democracy has been completely successful. This, in itself, is an indictment of the grand project that was meant to fill the void in Western Europe left behind by God and the continent’s cataclysmic experiments in nationalism. Knausgaard appears to be saying that, for all its material benefits, social democracy is a sterile force. It cannot imbue the lives of its citizens with purpose, nor can it foster a community of feeling.

We see the failures of this society everywhere in Book Five. Of the commuters on a bus: “They were going to work, I could see it in their eyes, they had that vacant wage-earner look.” Of his alcoholic father, whose deterioration reflects a post-war progression from stoic propriety to hippie-inflected liberation to ruinous torpor: “[H]e stood up in front of me in the semi-darkness, the fat bearded drunken man who was my father and had once been the very symbol of correctness—well dressed, slim and good-looking, a young respected teacher and politician.” Of the institution for the disabled where he works, which smells like an old school that he once described as a “social democratic fortress”: “I recognized the smell … a mixture of green soap and a faint odor reminiscent of cellars and sewage, something dark and damp and subterranean in all the assiduously maintained hygiene.” These failures become apparent in even seemingly innocuous passages, once the reader becomes attuned to the change in atmosphere. Book Four, for example, which is basically about Knausgaard’s epic quest to get laid, ends with him “pump[ing] away” at a girl in a tent at the Roskilde Music Festival as she vomits from drinking too much booze. What was once a fitting ending to a comic romp is now a depressing symbol of the emptiness of Western life.

It is an emptiness that our nature seems to abhor. As Mann writes in Doctor Faustus, his allegorical novel about the Third Reich that is conspicuously cited twice by Knausgaard in My Struggle: “Amidst disintegration, the search for the rudiments of new ordering forces is universal …” Knausgaard himself takes an almost mystical approach to these demonic ordering forces. During a fishing expedition on a fjord, shortly after he has reprimanded himself for exhibiting a Nietzschean contempt for his disabled charges at the institution, he writes this of an enormous fish he has caught, in a rare foray into high figurative mode: “It was as though it came from another era than ours, up and up it came from the depths of time, a beast, a monster, an ur force, yet there was something so clear and simple about it.”

Even a few years ago, this concern with the enduring appeal of fascism may have seemed like a stretch, a writer’s attempt to add historical weight to his novel by appropriating the leaden gravity of the Nazi era. But with right-wing revivals sprouting all across Europe, not to mention the rise of Donald Trump here in the United States, Knausgaard’s book is a reminder that if we are to understand this movement’s appeal, if we are to grasp the nature of this bewildering other, we should begin by looking inwards. As Knausgaard has written elsewhere of Breivik, who is supposedly discussed at length in Book Six: “Everything in Anders Behring Breivik’s history up until the horrific deed can be more or less found in every life story; he was and is one of us.”

Knausgaard, for his part, finds a tenuous salvation in repurposing old forms. Like Augustine, another of his literary predecessors, Knausgaard’s approach is to confess, even if he has no God to receive his confession. His reward, instead of heaven, is an intimation of the divine, which reveals itself when the artist is at his most god-like, deep in the fiery furnace of creation. On one level, this is art as religious experience, in which the artist feels as if the godhead is working through him; on another level, this is Freud’s sublimation at work, the transfiguration of dark thoughts and dark impulses into refinement and beauty. Freud considered this process a triumph of civilization, and in this respect, the salvation that Knausgaard is working toward is not only his own. It has always seemed audacious for Knausgaard to name his novel after Hitler’s autobiography-cum-manifesto, but Book Five is proof that we didn’t realize the extent of his ambitions. It turns out that his Min Kamp is meant to be Mein Kampf’s fraternal twin, and proof that the evil of their shared birthright can be overcome.