In February, Iranians went to the polls for yet another election. These affairs are never dull, and neither was this parliamentary race. More than 10,000 candidates filed paperwork to compete for 290 seats, but, of these, some 5,000 were rejected before Iranian voters even had the chance to do so. The disqualifications came at the hands of the Guardian Council, one of the bodies of the Islamic Republic’s byzantine political system, and most of those unable to run hailed from a political camp known popularly as the reformists. Reformism had coalesced as a political outlook in the 1990s aimed at liberalizing Iran’s harsh social strictures, remedying class divisions and ending the country’s international isolation. Despite the disqualifications ahead of this winter’s election, many reformist-minded Iranians cast their vote with moderates, centrists and even a few conservatives aligned with the aims of Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani.

Rouhani, whose government brokered the nuclear deal with world powers last summer, is distinctly not a reformist; he hails from the circle around a beardless cleric and former centrist president named Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. But this is the game in Iran: the reformist faction has, for some three decades now, sought out openings wherever it could find them and accepted allies in any form, not least because the country’s most powerful political force, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has had it out for them from the start. The latest parliamentary contest, then, was a reformist victory of sorts, not in the election of their own politicians, but in taking what they could get in the narrow bounds allowed by the nezam—system—within which they, better than anyone, know they must operate.

Though she barely arrives at Rouhani’s 2013 election in her epilogue, this delicate push-and-pull is similar to many situations described in Laura Secor’s new book on the Iranian reform movement, Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran. Secor, a magazine writer with intense experience and interest in Iran, reviews the history—namely, the origins of and tensions between the Islamic left and Islamic right—but the volume does so much more. The facts, of course, are all there: The book presents profiles and sometimes surprisingly intertwining narratives of a cast of characters who, though they have yet failed to win the soul of the country, formed the beating heart and main arteries of the Islamic left and later the reform movement. Over the top of these stories, however, Secor layers on a rich intellectual history.

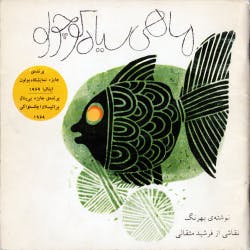

The journey could have begun at the turn of the century, when Iranian leftists started to organize in earnest and intellectuals began to coalesce around the aim of imposing a constitution that would restrain the absolute monarchy. But that would have been quite the tome, and Secor instead locates as a starting point the 1968 publication of a children’s book called The Little Black Fish, by a leftist author named Samad Behrangi. In the book, a little black fish finds its way from the stream to the sea and once there, in a dark conclusion, sacrifices itself so that another fish may survive an attack by a bird. Back up river, the narrator, an old grandmother fish, tells the bedtime story to a school of fish, leaving another fish—this one, what else for the man of the left, a little red fish—restlessly awake dreaming about the freedoms of the sea. Behrangi, in a poetic turn almost too good to be true, couldn’t swim and, the same year Little Black Fish came out, drowned in the powerful current of a remote river.

From there, we’re off. One of Behrangi’s friends, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, fashioned the young author’s life and death into a folk tale of its own, an inspirational parable for leftists struggling under daunting odds against the monarchy. Al-e Ahmad also made a foundational contribution to the revolutionary impulses stirring among leftists and Islamists alike: An essay he wrote in 1962 called Westoxification implored Iranians to cast off the corruptions of Western influences—especially those being foisted upon Iranians by the autocratic and aspirationally modernizing shah. Another thinker, the lay religious radical Ali Shariati, laid leftist notions of class struggle upon a framework of Shiite Islam, Iran’s dominant sect. With his innate charisma, Shariati would rally scores upon scores of students into militant opposition to the shah’s regime.

Not unlike other ideas that gave rise to the 1979 Islamic Revolution—not least among them the revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s theologically groundbreaking formulation of velayat-e faqih, or rule by Islamic jurisprudence—notions like Westoxification and Shariati’s sort of liberation theology would be at various times seized upon by the hardest of hard-line revolutionaries or rejected by them, carried out to extremes or suppressed by force, but always debated among the more liberal and left strains of the Revolution’s victors.

The proliferation of these intellectualized disputes is where Secor is at her best, deftly weaving a narrative that encompasses the top-level machinations and history of the Islamic Republic, but also including what might be considered the middle-management of reform. There are profiles of editors of intellectual journals, journalists, activists, aides to the political names we should all know well by now and, in a few fascinating cases, the opponents of these strains of thought Secor clearly admires. The narratives are accompanied by concise exegeses on the ideas themselves. The academic Abdolkarim Soroush, for instance, excited a generation of Islamic Republicans by harnessing Karl Popper—a relative unknown among Iranian philosophy departments—against godless Marxism, but eventually evangelizing along the lines of Popper’s call for open societies. Secor describes the theories of urban development—or in the case of the capital Tehran’s chaotic post-revolutionary boom, the lack thereof—and places them in their context as the sites of battles over politics: Reformist intellectuals sought to use municipal governance to sow seeds of, as one intellectual put it, “political development” at a low level that could be reaped by a national movement

These debates and the theories laid out therein seem in retrospect almost absurdly abstract, for the Islamic Left and later the reformist movement never achieved enough power to thoroughly impose these ideas as any sort of lasting policy. And yet the very notion of debate itself would be essential to reformist aims: for these children of the Revolution, the system they had helped erect was strong enough to withstand the internal scrutiny of a free-thinking academia and press. The hard-liners in charge, however, demurred over and over again. The import of the ideas reformists fought for would be perversely proved in the price paid in blood by those who dared to imagine them possible. This was ever the tale of the Islamic Republic: the idealism of the Islamic Left against the empowered, brute force of the Right.

If the Islamic Left—those revolutionary mollahs, intellectuals and politicians who became the reform movement—had wanted to know what was in store for them, they might have glanced further to their own left. At the time of the revolution, a Shariati-inspired group of lay radicals espoused a militant blend of Marxism and Islamism. The Mojahedin-e Khalq (Holy Warriors of the People) organized lower- and middle-class university students into fighters and, despite the Shah’s crackdown, maintained enough force to be a factor in fighting at the vanguard of the Islamic Revolution. But the alliance with Khomeini was tenuous, at best, and the Mojahedin suffered from its own eccentricities; by that time, the Mojahedin had coalesced around a charismatic leader named Massoud Rajavi, who would later lead the group into being little more than an armed cult of personality. When it became clear that Khomeini had no intention of sharing too much power with these lay, Marx-inspired radicals, Rajavi bristled, and Khomeini cracked down with violent force, sending many of the group’s members to prison, to exile or to their graves.

Secor’s history of post-revolutionary Iran points to this pattern again and again: The Islamic Left and later its inheritors in the reform movement gain some cachet and press at the outer boundaries of what is permissible to the hard-line leadership, only to have their progress and hopes dashed by force. Then the circle of acceptable discourse shrinks to exclude them. Khomeini had kept the religious Left and Right at odds, playing them off each other but never definitively picking a side, all the better as the Left helped shepherd the new country through a difficult period of isolation and a devastating, long war with Iraq. But when Ali Khamenei came to power in the late-1980s, he sided unequivocally with the right against all comers. Driven into the political wilderness, the Left holed up in academia and journalism. Then in the mid-1990s, reformism leapt out of the pages of journals and newspapers into the political scene: A smiling and unlikely cleric named Mohammad Khatami swept into the presidency and with him a group of sometimes aloof intellectuals into parliament.

Even this unified elected government, however, faced resistance from more powerful corners, exposing a pattern that holds as true today as it did then: Khamenei and his claque controlled the unelected structures of government, such as the army of the Revolutionary Guards, other security forces like the Basij militia and the judiciary. Small gains were made: Newspapers sprung up like the sprouts all Iranians grow at their New Year’s tables; the excesses of the state, such as a series of murders of intellectuals and dissenters by those closely linked to the seat of power, came under unprecedented scrutiny; “civil society,” by now a buzzword for a network of NGOs and community groups focused on progress, blossomed; and Khatami’s reassuring face signaled a willingness to end Iran’s international isolation.

Yet the power of reactionaries was too great; Khatami proved ineffectual, sometimes for timidity, though perhaps a knowing one. His reforms were not lasting, but the hope for a better life visited upon huge swaths of Iranian society held, even as the progress made vanished. With the hard-line right-wing president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who, not without some irony, emerged from Tehran’s city council and mayor’s office, skies darkened over reformist circles. Newspapers and journals closed; academics with any modicum of a reformist bent came under pressure; and the government cast a wary eye upon civil society groups.

The storm finally came with the June 2009 presidential election. The thunderclaps were the gunshots of security forces that left dead dozens of protesters disputing Ahmadinejad’s victory over an early Islamic Left stalwart named Mir Hossein Mousavi, who had abandoned politics for two decades and emerged as the leader of a reformist campaign that would come to be called the Green Movement. Blood spilled from overcrowded prisons, rife with torture and rape, deaths in custody of ordinary protesters and organizers alike. Mousavi and other reformist leaders of the protest would after not too long be placed under house arrest—if they were lucky—without charge. Khatami, a two-term president, eventually became persona non grata; newspapers were forbidden to print his photograph or even his name.

Secor renders the ecstatic rise and bloody fall of the Green Movement through the eyes of a poet and journalist turned anti-stoning and women’s rights activist, Asieh Amini, tracing with her the hopes in Mousavi and their brutal crushing. Amini’s friends disappeared from the streets and before too long it became evident that she, too, was at risk. She fled with her daughter and, later, husband to Norway.

Thus the circle shrank yet again, and yet again, no matter how small it became, Iranians found a way to have their debates. Soon enough, Rouhani would emerge—not a reformist, but with reformists’ blessing, and facing the same problems they did. Hard-liners in the security forces and judiciary continue to run amok. The human rights of Iranians are still violated, often with impunity. And yet Rouhani was able do the unthinkable: strike a deal with, among other much-demonized Western powers, the United States.

Like many of his compatriots, Rouhani and his ruling cohort, particularly his reformist-aligned foreign minister, Javad Zarif, seem to understand America better than most Americans—and especially our politicians—seem to understand Iran. Rouhani’s entreaties to diplomacy were met in Washington with receptiveness from one end of Pennsylvania Avenue and unmitigated hostility from the other. Yet the seemingly implacable forces of reaction in both Tehran and D.C. were held at bay long enough to make a deal that should give ordinary citizens of both countries a moment to breathe easy—at least for now.

Americans, for their part, might take this moment to enjoy Secor’s book to gain a better understanding of Iran’s rich recent history. In it, they will find this lesson: the circle may tighten around intellectual life in Iran, around political progress, and around the complicated heroes who hold down, often unsuccessfully, those barricades—but the ideas that animate these figures and their impulses, the debates behind them, will live on underground, behind closed doors, until it’s time to bloom again. Secor’s story has almost nothing do with the United States—it is a refreshingly Iranian tale—but for us there is this implicit warning: Do not trample this soil and foreclose that next Spring.