American Idol was “born” exactly nine months after 9/11. The timing was significant, because since its premiere on June 11, 2002, the show has become an integral part of the country’s coping strategy—a kind of guidebook for our difficult entry into the twenty-first century.

By carefully curating a distinctly American mixtape of music, personal narratives and cultural doctrine, “American Idol” has painted a portrait of who we think we are, especially in the aftermath of tragedy, war and economic turmoil.

As the show concludes after 15 seasons, it’s worth looking at how the past and present collided to create a cultural phenomenon—and how we’re seeing shades of the show’s influence in today’s chaotic presidential race.

All our myths bundled into one

American Idol’s premise—the idea that an ordinary person might be recognized as extraordinary—is firmly rooted in a national myth of meritocracy.

This national narrative includes the dime-novel, rags-to-riches fairy tales of Horatio Alger, which were intended to uplift Americans struggling to get by after the Civil War. Then there was the American Dream catchphrase—first coined in 1931 by James Truslow Adams in his book The Epic of America—that promoted an ideal of economic mobility during the hopeless years of the Depression.

Indeed, decades before host Ryan Seacrest handed out his first golden ticket to the first golden-throated farm girl waiting tables while waiting to be “discovered,” we’d been going to Hollywood in our dreams and on screen.

The show has shown us archetypes of immigrant narratives, like when season three contestant Leah Labelle spoke of her Bulgarian family’s defection to North America during Communist rule. It has demonstrated how to rely on faith in the face of hardship, exemplified by Fantasia Barrino’s victory song, “I Believe,” performed with a gospel choir. Meanwhile, it served as a stage for patriotic passion, broadcasting two performances of Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.” when the United States entered Iraq in 2003. Meanwhile, the many “Idol Gives Back” specials remind us of American philanthropic values.

The show has celebrated failure as both a necessary stumbling block and a launchpad to fame. Many singers needed to audition year after year before they earned their chance to compete. For others, such as William Hung, their televised rejection brought fame and opportunity anyway.

“American Idol” has also served as a course in American music history, featuring discrete genres like Southern soul and Southern rock, together with newer, blurrier categories like pop-country and pop-punk.

Making the old new again

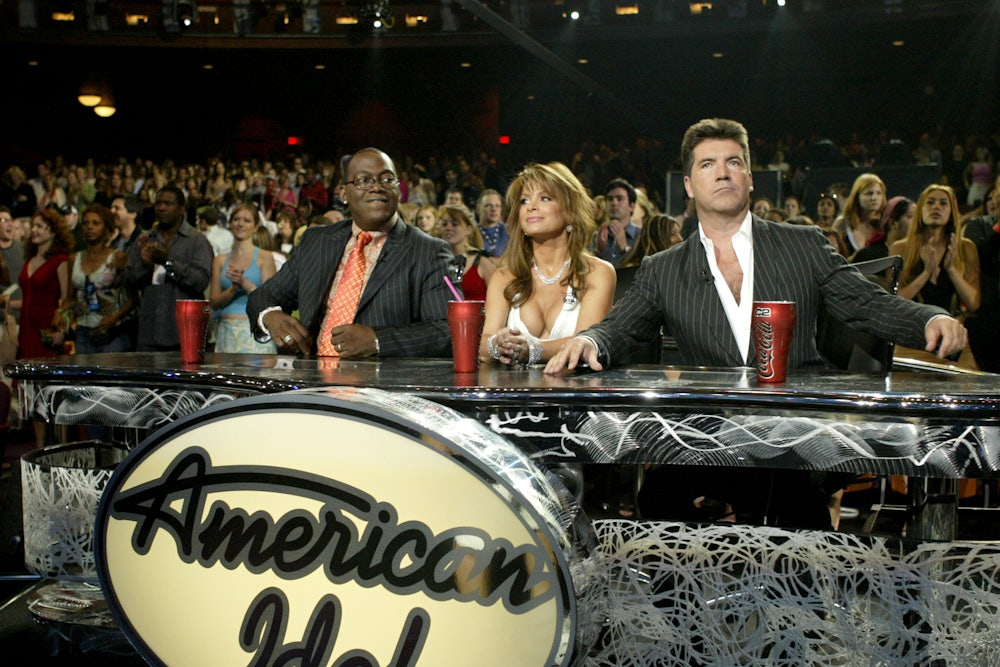

In one sense, American Idol’s format was nothing new. In fact, British entertainment executives Simon Fuller and Simon Cowell—who shepherded in a twenty-first century version of the “British Invasion”—fashioned their juggernaut show as a new take on old business models.

There is something distinctly American about contestants standing in a Ford-sponsored spotlight, judges sipping from Coca-Cola glasses, and viewers sitting in front of television screens texting their votes on AT&T phones. The show’s conspicuous commercialization recalls the earliest days of television, when programs were owned and produced by advertisers. And Idol, like that early programming, was intended to be “appointment television,” bringing families together at the same time every week.

Idol’s production model is also a throwback. It’s structured like Berry Gordy’s Motown —a one-stop fame factory that offers stars a package of coaching, polishing, a band, album production and promotion.

The format also draws from amateur regional and national radio competitions of the early twentieth century. (Frank Sinatra got his start winning one on Major Bowe’s Amateur Hour in 1935, with the Hoboken Four.) Another influence is the half-ridiculous and totally political Eurovision Song Contest, the hugely popular and mercilessly mocked annual televised event that pits nation against nation in (almost) friendly singing competition.

A vote that counts?

Eurovision, which originated in 1955 as a test of transnational network capabilities and postwar international relations, introduced telephone voting a few years before Idol premiered.

And like Eurovision, the impact of American Idol extends far beyond our annual crowning of a new pop star. The show’s rise has taken place at a time when the boundaries between entertainment, politics and business have become increasingly blurred.

Season after season, American Idol fans have placed votes for their favorite contestants—options which, somewhat like our presidential candidates, have been carefully cultivated by a panel of industry experts looking for a sure bet.

The initial success of Idol heralded not only an era of similar television programming, but also a new era in which we’re given the opportunity to “vote,” whether it’s for dum-dum pop flavors or the world’s most influential people.

Considering these trends, it’s not so farfetched to suggest that the wild popularity of shows like American Idol played some role in setting the blinding chrome stage and slightly “pitchy” tone for this year’s election.

It isn’t just that Donald Trump presided over The Apprentice, a reality competition that rode in on American Idol’s coattails.

His persona also seems to meet the same sadistic public need satisfied by original Idol judge Simon Cowell: The executive heir, the imperious arbiter of taste who owes his fortune at least as much to his superiority complex as to any financial acumen. At the same time, personas like Cowell and Trump deign to give an ordinary, hardworking American a chance.

That conceit, though, is mitigated cleverly by both moguls: They capitalize on what Cowell has identified as a universal desire to feel important.

The crux of their personal appeal is that they understand that everyone wants to matter, and we are willing—as TV viewers or as citizens—to risk an awful lot just to feel like we do. We each want to imagine our own sky-high potential, and laugh in relief when we see others who will never get off the ground. We want to be judge and jury, but also be judged and juried.

Idol gives Americans permission to judge each other, to feel like our opinion makes a difference. Trump’s unfiltered rhetoric has done something similar, giving his supporters implicit and sometimes explicit permission to mock, dismiss, exclude and even attack others based on racial and ethnic identity, religion or ability.

And so now, as Idol makes its final journey from Studio 36 to the Dolby Theatre, we deliberate over whose victory will herald the last “Seacrest—out.”

Whatever happens, and whichever way our presidential election goes, the U.S. is on the brink of something new, a major cultural shift. Wherever we’re going, Idol has served its purpose, and we don’t need it in the same desperate way anymore.

I think, though, that we’ll always be searching for the next big thing. And we’ll always be glad we had a moment like this.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.