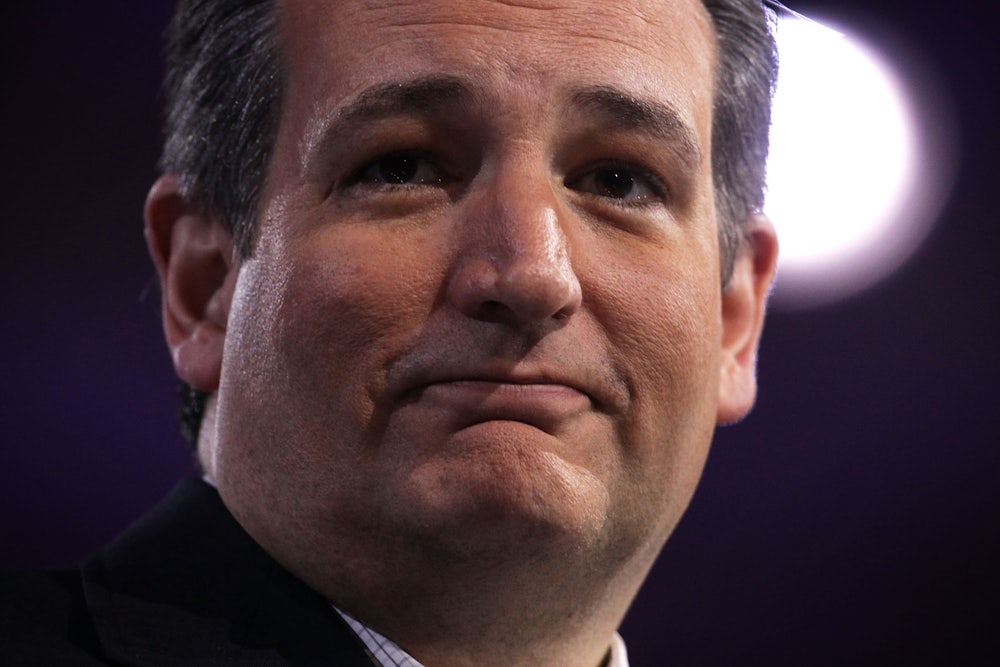

From his Princeton undergraduate days to his current presidential run, Ted Cruz has notoriously been a difficult man to like. We have ample testimony that he’s abrasively arrogant, nakedly self-aggrandizing, suspiciously oily, and generally repellent. Many of Cruz’s Republican colleagues in the Senate bear a special grudge against him, because of the way he riled up the Tea Party base by painting them as sellouts and compromisers. Cruz’s role in engineering the 2013 government shutdown has not been forgotten by still-bitter peers.

But in the most bizarre GOP primary since at least 1964, many Republicans are discovering a strange emotion: grudging respect toward Cruz as the last remaining hope to stop Donald Trump. The Texas senator has become the default savior of the Republican establishment, earning their support by a process of elimination that has left him the only barely tolerable option. The question now, for Cruz and the party, is how many of these half-hearted supporters he can rally. Cruz is now in the process of crafting an incoherent coalition—one half made up of right-wing zealots who adore him, the other by disheartened establishment Republicans who only support him because the alternative is so wretched. It’s hard to see how a candidate can keep these two disparate factions together.

With Cruz leading in the Wisconsin polls, not to mention being Trump’s only remaining rival to have won one more than one contest—in contrast to John Kasich, whose victory in Ohio was strictly a home-state affair—the Texas senator is the only Republican candidate left for those who regard Trump as an unmitigated disaster. For the GOP’s #neverTrump brigade, the hope is that Wisconsin will reshape the race and be the pivotal moment the tide turns against Trump.

In January, before he pulled the plug on his own presidential campaign, Senator Lindsey Graham spoke for many Republicans when he said the choice between Cruz and Donald Trump was “like being shot or poisoned. What does it really matter?” Yet by the end of March, Graham had come around to accepting Cruz as the more palatable evil. “He’s not completely crazy,” Graham noted on The Daily Show, explaining why he joined the “Ted train.” Returning to his older metaphor, Graham added, “Donald is like being shot in the head. You might find an antidote to poisoning, I don’t know, but maybe there’s time.”

The backhandedness of Graham’s endorsement illustrates the key problem Cruz will face even if he wins in Wisconsin. Hardline conservatives are Cruz’s core base. But to move beyond his current status in second place and secure the nomination, he needs to attract many more people like Graham, who have a history of animosity toward him. In effect, Cruz’s path to victory means combining two completely opposed constituencies. And they just happen to be constituencies that he’s worked hard to set in opposition against each other.

If Cruz is able to pull off this seemingly impossible balancing act, it’ll be thanks to a quality he rarely gets enough credit for, his wholesale cynicism. Cruz is so surrounded by animosity that it is rarely noted that there are two contradictory accounts given as to why, beyond his personality, he is so odious.

Many liberals and moderate conservatives see Cruz as a fanatic, a true believer who is willing to enact extreme policies like the government shutdown in order to advance his dogmatic vision. This was the Cruz portrayed by Jeffrey Toobin in a 2014 New Yorker profile titled “The Absolutist.”

Yet some Republicans who share Cruz’s professed conservative politics don’t see him as an ideologue at all. They view him as a cynic who craftily adopted their worldview out of self-interest, to win over the faction he needs to win the Republican presidential nomination. Writing in The New York Times, Ross Douthat offered this analysis of Cruz as he shifted from being a Bush loyalist to head of the right-wing counter-establishment:

Then once installed as a leader of the counterestablishment, he walked a line that looks ... far more calculated than most conviction politicians. While his fellow Tea Party senators, from Paul to Rubio to Utah’s Mike Lee, built detailed policy portfolios that fit their interests and inclinations, Cruz never seemed to take a step on any contentious issue without gaming it out 17 moves ahead.

His push for the Obamacare shutdown, and the bill of goods he sold the party’s base, was a particularly remarkable exercise in self-serving political cynicism. But on many fronts—Edward Snowden, trade policy, immigration, the fate of Middle Eastern Christians—Cruz has proceeded with several fingers in the wind; every time the conservative mood has shifted even a little, he’s shifted quickly too.

This is an unflattering portrait, to say the least, but it offers a glimmer of hope for Cruz’s reluctant new allies such as Lindsey Graham. For if it turns out that Cruz is really more of a cynic than a zealot, then he might indeed be capable of moderating and working with them once he gets the nomination. It might be in Cruz’s best interest to drop a few hints to the establishment that he’s not the purist ideologue that some have made him out to be, that he’s more Tallyrand than Robespierre, more crafty Stalin than true-believing Trotsky. This would mean encouraging others to have an even lower opinion of his morals, but a higher opinion of his pragmatism. Such an overture to the establishment might overcome any lingering doubts the Lindsey Grahams types have and make them truly eager to join the “Ted train.”

In turning to Cruz as their last-ditch savior, the Grahams of the world need to find whatever virtue they can in him. Perhaps Cruz’s saving grace will be that he really is, as Trump says, Lyin’ Ted.