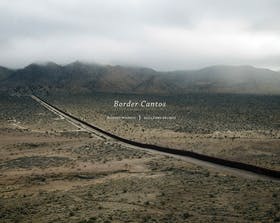

The nearly 2,000-mile border between the United States and Mexico is as unpredictable as the relationship between the two countries it divides. High walls in the desert funnel would-be migrants to Border Patrol outposts, while militarized barriers splice border towns in two. To fully wall off the border, as Donald Trump is proposing, would require about 1,300 additional miles of fencing, at an estimated cost of $25 billion.

If this scarred landscape could speak to us, what would it say? This question is at the heart of the artistic collaboration between American photographer Richard Misrach and Mexican composer Guillermo Galindo in Border Cantos, published earlier this year by Aperture. Their images, music, and sculptures give voice to the millions of border-crossers for whom the journey signifies the difference between money and poverty, safety and death.

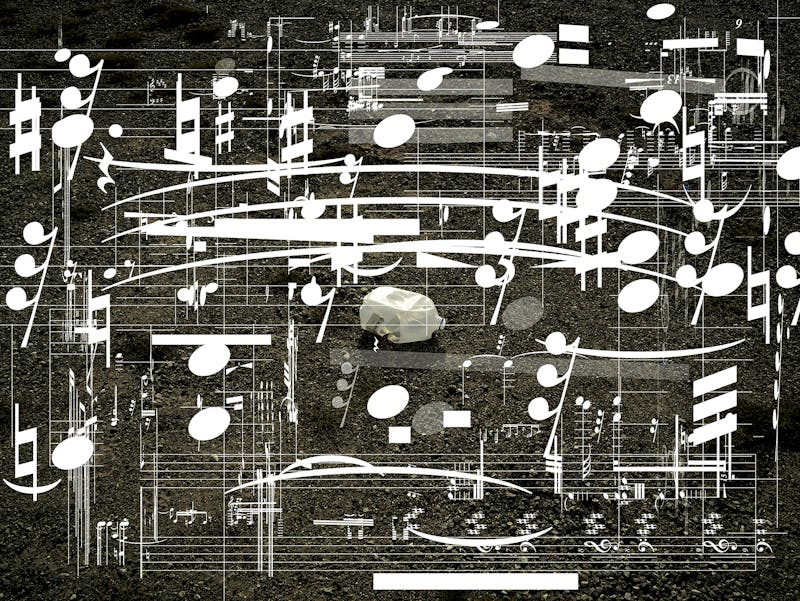

Misrach has been photographing the border wall since 2004. On each of his visits, he collected objects including discarded backpacks, bone-dry water bottles, and inner tubes used to cross the Rio Grande. He began shipping the artifacts on to Galindo, who used them to build instruments and compose music featuring his inventions. (Galindo’s musical compositions and Misrach’s photographs are currently on exhibit at the San Jose Museum of Art.)

Misrach found this jug in Arizona, and Galindo filled it with gravel to make it a shaker. He would often request specific items from Misrach that could evoke specific types of sound—the harsh clink of shotgun shells or the crinkle of a discarded gum wrapper. “I saw the landscape as a big orchestra,” Galindo said of his own experience visiting the border. “The sound that every object produces is attached to its existence in the world.”

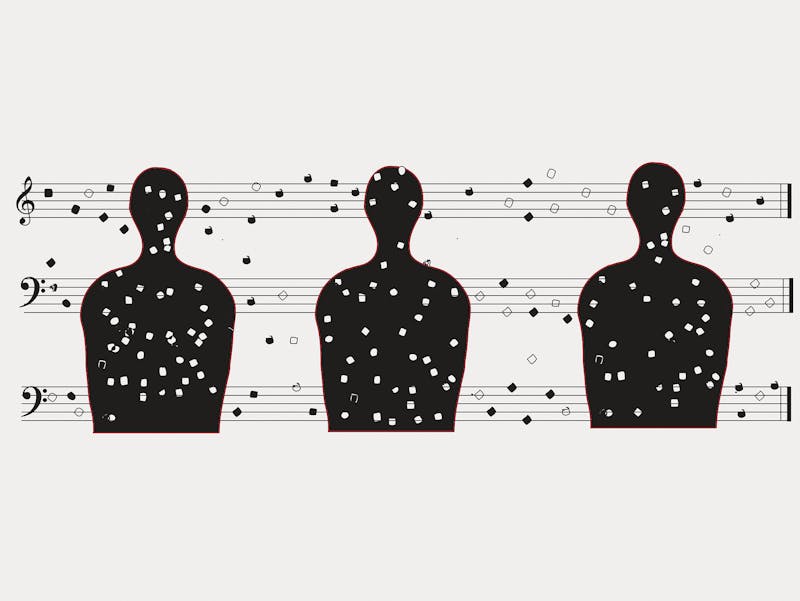

This metal piñata, made from a soccer ball found on the U.S. side of the border, is inspired by a West African instrument called a shekeré. A traditional shekeré is made of a gourd, and covered in a net of beads or seashells. For his version, Galindo created a “bittersweet aesthetic” using spent shotgun shell casings found at a Border Patrol shooting range.

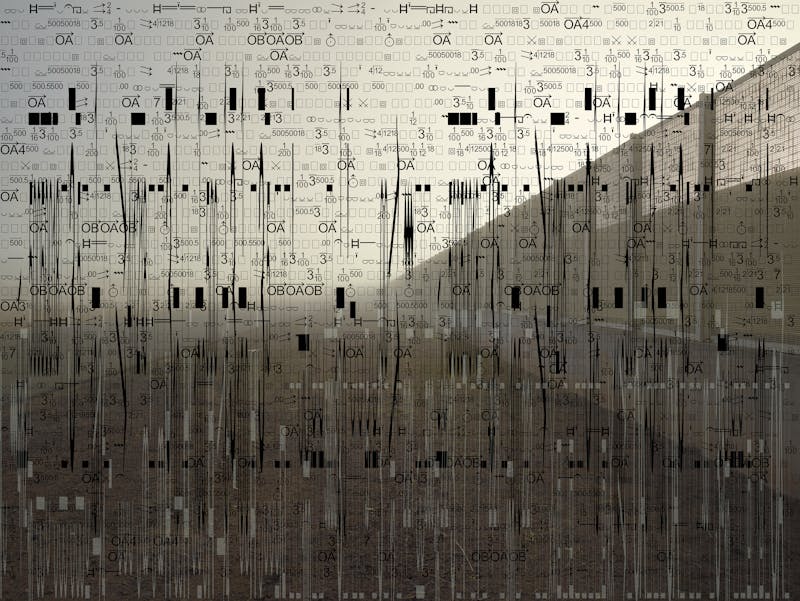

“I’ve been photographing for 40 years,” Misrach said of his foray into multimedia collaboration, “and normally I shut out everything except the visual. But suddenly with Guillermo, I could hear everything around me. When I photographed the shotgun shells, I grabbed some.” Misrach and Galindo first met in San Francisco, after Misrach attended a pop-up magazine performance featuring Galindo’s compositions. “We’re not only bridging the notion of the two cultures, but also our two mediums,” Misrach said. “It’s a nice metaphor for what should be happening with the border.”

To track migrants, Border Patrol agents use an old Native American tracking technique called “sign cutting” or “cutting for sign.” They drag tires behind trucks to smooth out the dirt and desert sand, making it easy to see footprints or other signs of life.

The border fence runs past a private residence in Texas. Unlike most Bush-era construction, which took place on federal lands, Trump’s proposal would forcibly displace thousands of homeowners.

Human faces are noticeably absent from Misrach’s photographs of the borderlands. Of the landscapes, he said “I use [their] beauty as a strategy. I use it the way Jon Stewart uses humor—to get people to see things in a new way.”

Tonk, the name of this plastic trumpet fashioned out of a Border Patrol flashlight, refers to the derogatory name some Border agents call migrants: “Tonk” is the sound a flashlight makes when hitting someone’s skull. When making his instruments, Galindo noted that the sounds related to immigration enforcement tend to producer harsher sounds, due to their tougher materials, while the immigrants’ items are much quieter. “It’s very interesting how everything follows some kind of logic in the end.”

Between 1998 and 2012, the average number of deaths per year along the border was 373. Most die of heat exposure. As enforcement grows, people are pushed into more remote areas, in an attempt to avoid agents.

Misrach first photographed this isolated segment of the wall near Los Indios, Texas, in 2012. Returning three years later, he expected to find additional construction, but the only change he saw was the patch of green grass growing around it. Because the land was purchased under eminent domain, Misrach estimates that this single piece of fencing cost more than half a million dollars to build.

Richard Misrach’s photographs are Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, Pace/MacGill Gallery, and Marc Selwyn Fine Art.