The great central valleys of California have produced almost as much literature as fruits and vegetables: Mark Twain, Frank Norris, Steinbeck, Saroyan, and a hundred off-shoots grew amidst the beets and grapes and cotton and spinach. From it emerges a rough provincial epic: the struggle of poor settlers against an uncompromising land and the equally uncompromising businesses and bosses who exploit them.

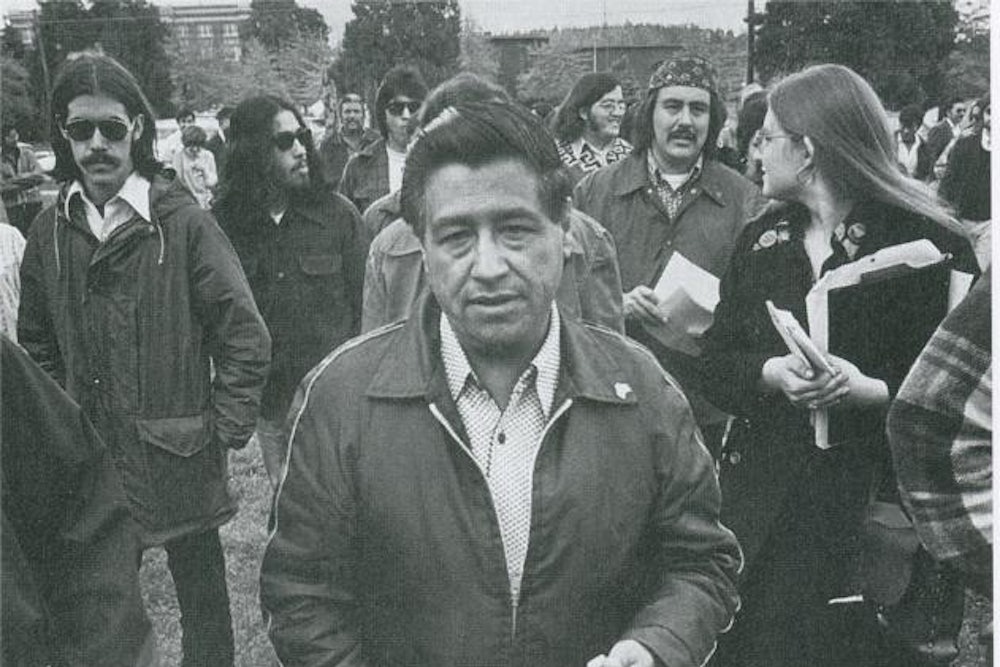

The epic hero of these times is Cesar Chavez, a short, dark, mild Mexican-American who is building a strike of grape-pickers in the San Joaquin Valley into a new kind of labor war. It is a long time since the valley saw such battles; Chavez says the strike is the biggest organizing effort in California agriculture since the Modesto “cotton wars” of the late 1930s. Whether Chavez will succeed where everyone else failed is still problematic. The strike is in its fifth month, and the grape harvest on the 35 ranches affected was more bountiful, if less profitable, than ever before. But Chavez’s idea is not primarily to win small benefits or even long contracts. He is out to develop a community of farm workers, and his methods are more like a civil rights worker’s in Mississippi or a ghetto organizer’s in Chicago than a union leader’s. He is not in the valley for a season of agitating. He came to stay.

Chavez was born in Arizona. His family came to California during the depression, and he grew up in the valley town of Delano, now the epicenter of the 400-square-mile strike zone. For a time he worked among Mexican-Americans on the staff of Saul Alinsky’s Community Service Organization. Three years ago he and two other workers left CSO to form the independent National Farm Workers Association. Wages and working conditions were the obvious first concerns of organizing; farm workers in Delano, for instance, have a median family income of about $2,000 a year—and often 10 children to support (the California median is $6,726). State standards (toilets and drinking water in the fields, rest periods) for farm work are largely ignored. Worst of all, the workers have no right to organize, no guarantee of a minimum wage and no protection under federal labor laws.

Chavez tried small strikes against individual growers up and down the valley, but his principal effort was in Delano, where he had lived and worked, and where his wife was raised. Last spring he applied for a Poverty Program grant to train community organizers in money management, literacy teaching, family education—the skills required to bring the grape-pickers in from the fringes of life in their own town.

The proposal was going through the Washington maze when, on September 8, AFL-CIO farm labor organizers called a strike in Delano. Big labor’s history of organizing California’s “agribusiness” had not been noticeably successful. In 1959, the labor federation formed an Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) and sent an agent up and down the valleys in search of members. The main effort centered in the Imperial Valley of Southern California. A long, bitter strike of lettuce-pickers finally collapsed, in early 1961, when two unions fell into a jurisdictional dispute over the membership of the workers. Labor leadership in Washington let the effort fail.

For the most part, the Mexican-Americans did not trust the “Anglo” labor organizers; they suspected the agents were luring workers into agricultural unions for no better reason than to collect dues and help the industrial unions—which frequently discriminated against the Latins. And so when the AWOC members walked out of the Delano fields, there were few Mexican-Americans among them. Most of the AWOC strikers were Filipinos.

Chavez had thought his community was ill-prepared for a strike, and he was reluctant to risk failure. But in a few days he saw that it would be far worse to break the strike by ignoring it, and his Farm Workers Association formed a joint strike committee with the AFL-CIO leadership. The alliance has held up well, but the character of the strike has been almost completely molded by Chavez. He invited workers of the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee into Delano to help organize and to help picket. He adopted a credo of nonviolence, and proclaimed it to the community and the growers (it was, in different ways, irritating to both). He encouraged clergymen to help the strike, and he went to Stanford and Berkeley to get student support. His constituency was developing in the same groups that had been backing the civil rights movement: students, preachers and middle-class liberals. What was amazing was that they had forgotten about labor organizing for 25 years or more, and were now coming back.

End of the Bracero Program

In two weeks, the growers’ work force was reduced by over half. Then the scabs started coming—first from other valley towns, and when they joined the picket lines or refused to work, from out-of-state. Growers bused in workers from Texas and old Mexico. Some hired “wetbacks.” The bracero program (importation of cheap Mexican labor under federal auspices) had officially ended ten months earlier, and the resulting shortage of farm workers made a strike seem feasible. But Labor Secretary Willard Wirtz caved in halfway through the season. He allowed the importation of 20,000 Mexicans, and the sudden surplus encouraged the growers to hold out.

Chavez and the AWOC leaders were asking for a minimum wage of $1.40 an hour, and an incentive rate of 23 cents per basket (a good worker picks about four baskets an hour). The average wage in the valley was $1.20 an hour and 10 cents per basket. The strikers also demanded enforcement of the “standard” working conditions. But more than that, they wanted recognition as a union. The growers flatly refused. All but three of the ranchers refused even to open the registered letters Chavez sent asking for negotiations on the eve of the strike. The growers treated the strikers as if they were members of the Viet Cong: ignore them and they will go away.

The strikers did not disappear, and although the imported workers were getting much of the harvest in, the growers felt beleaguered. Teams of roving pickets started at four in the morning and followed work crews. As the day began, the pickets stood at the roadside and shouted “Huelgal” (“Strike!”) to those in the fields. At first, relatives were shouting to relatives; then most of the Delano workers were in the road shouting to bused-in strikebreakers. The growers went to court and got a temporary restraining order forbidding the pickets to shout, and the growers moved scabs to the middle of fields to avoid contact with the pickets. Some growers went down the margin of their fields with spraying machines, shooting insecticide and fertilizer at the pickets. More commonly, foremen would race along the roadside in tractors, swirling up dust to choke the strikers. Some put farm machinery between the workers and the pickets, or followed the pickets with machine motors racketing at full throttle to drown out their calls.

The Mechanics of Picketing

Where the pickets could be seen and heard, they were remarkably successful (the imported workers had not been told they were going to be strikebreakers), but the mechanics of picketing 35 ranches was staggering. “It’s like striking an industrial plant that has a thousand entrance gates and is 400 square miles large. And if that isn’t bad enough, you don’t know each morning where the plant will be, or where the gates are, or whether it will be open or closed, or what wages will be offered that day,” a SNCC worker in Delano said.

Police and sheriff’s deputies were usually on the growers’ side. A minister was arrested for reading Jack London’s definition of a scab (“a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a water-logged brain, and a combination backbone made of jelly and glue. Where others have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles.”). Soon afterward, 44 pickets were arrested. Dolores Huerta, the Farm Workers Association vice president, was arrested twice in a week; the second time, she and a group of strikers were charged with trespassing and released on a total payment of $12,144 in bail. The few growers arrested for violence were let go on their own recognizance. Chavez and a Catholic priest were arrested for “violating air space” of a grower. They had flown in the priest’s plane to make contact with pickets sequestered in mid-field. Larry Itliong, the leading Filipino organizer for AWOC, was arrested on very dubious charges of “malicious mischief.”

The growers managed to bring in all but about 500 of the 30,000 acres of grapes, but their profits were cut. The unskilled laborers spoiled tons of grapes that the trained Delano workers could have packed carefully. Labor importation costs were huge; distribution was hindered by picket lines around trucks and on the San Francisco docks (Harry Bridges’ longshoremen’s union refused to load the President Wilson with Delano grapes bound for the Orient). Teamsters were, at least theoretically, helpful; the truck drivers were pledged to honor the picket lines, but AWOC strikers claim that truckers merely stepped from their cabs at the lines and let growers’ representatives drive them across for loading. But Teamsters cooperated at the produce markets.

In the middle of the strike, the Office of Economic Opportunity granted Chavez $267,000 for his community organization project. The growers were furious; they saw the money as a way to continue the strike. But Chavez was not very happy either. He knew it would be difficult to keep the strike and organizing separate, as the OEO had to demand. More than that, he could not spare the few trained organizers he had working on the strike to begin directing the community program. Finally, he asked the OEO to keep the money in abeyance until the strike was over. Sargent Shriver happily agreed. Pressure was already mounting against the funding-most prominently from Rep. Harlan Hagen, a more or less liberal Democrat from the Delano district. Hagen’s liberalism did not extend to unionization in his home county. He flew to Washington and berated OEO officials. Delano city councilmen (none of the five are Latin or Filipino, although half the town’s population of 13,000 is non-Anglo) first voted themselves a $9,000 raise as the official poverty board, and then requested that Chavez’s OEO grant be turned over to them.

Despite the pressure, the OEO is holding firm, but indications are that Shriver is looking for a way out. There is talk of giving the money to another agency in Delano “friendly” to Chavez, if one can be found, or more likely, formed.

The strike itself is continuing through the pruning season. Operations in the vineyards during the winter and spring months call for fewer but more highly skilled workers, and Chavez and AWOC hope that the strikebreakers will not be able to do it. Consumer boycotts of Delano grapes and wine have spread in California, and civil rights and religious groups are hoping to make them nationwide. (The major producer is Schenley, which makes Cresta Blanca and Roma wines from Delano grapes.) A group of eleven Protestant, Catholic and Jewish clergymen went to Delano last month and issued a strong statement for the strikers: “Those who labor on our California farms deserve the same active support that . . . Christians and Jews have given to the basic demands for justice for Negroes in the South.” (The Catholic was criticized by his superiors for the action.)

After the AFL-CIO convention in San Francisco in early December, Walter Reuther flew to Delano as a gesture of encouragement for the strikers. The labor federation gave a $10,000 present to the joint strike committee, and the United Auto Workers and the Industrial Unions Department (both Reuther’s) ante up other funds. It seems the least they can do. For years, the big unions have sold out agricultural labor; union lobbyists habitually tack on benefits for unorganized farm workers to new state and national legislation, and then compromise them away to obtain advantages for the organized industrial workers.

Farm labor remains the last unorganized bloc of American workers. No one has any reliable methods yet for organizing the migrant workers, but Chavez’s model is at least promising for the laborers already settled in towns. He disdains the traditional method of industrial unionizing:

“The danger is that we will become like the building trades,” he said in an interview with the SNCC newspaper, The Movement. “Our situation is similar—being the bargaining agent with many separate companies and contractors. We don’t want to model ourselves on industrial unions; that would be bad. We want to get involved in politics, in voter registration, not just contract negotiation. Under the industrial union model, the grower would become the organizer. He would enforce the closed shop system; he would check off the union dues. One guy-the business agent-would become king. Then you get favoritism, corruption. The trouble is that no institution can remain fluid. We have to find some cross between being a movement and being a union. The membership must maintain control; the power must not be centered in a few.”

Chavez thinks that industrial unions lost their opportunity to keep fluid, to remain progressive, when they concentrated all their efforts on winning a contract and then quit. His Farm Workers Association is build ing cooperative institutions—a credit union, co-op stores and gas stations, a funeral insurance club, and services to help Spanish-speaking semiliterates get what’s coming to them, from driving licenses to welfare assistance. More than that, he wants to see the grape-pickers of Delano become a powerful part of their community, as their numbers and their economic roles indicate that they should.

Quiet—withdrawn, even—and magnetic, Chavez is often compared to SNCC’s Bob Moses, who had the same kind of communitarian vision when he went to Mississippi in 1961. Chavez carries less metaphysical baggage around than Moses did (Chavez is, after all, a generation older), but it is clear that they are both working from the same conception of a good, if not necessarily Great, society. It is far from the individualistic idea the unions had a half century ago. The end of that process was simply to give workers a leg up to the middle class, and be done with them. The new way is quite different—to give workers a decent income and all the while build a society in which they can participate in the decisions which will affect their lives. As it is now, they must leave those decisions to the growers.