On September 18, 1960, four months before the U.S. severed diplomatic relations with Cuba and 56 years before Barack Obama would become the first sitting American president in almost a century to step foot on Cuban soil, Fidel Castro arrived in New York City for the 15th session of the United Nations General Assembly.

Castro had taken in the Big Apple the previous year, fresh off the successful overthrow of U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista. He ate ice cream at the Bronx Zoo, and posed for smiling pictures with blond-haired children. Wherever he showed his scraggly bearded face, from Yankees Stadium to the New York Press Photographer’s Ball, the fatigue-clad prime minister was fawned over like a celebrity—even as animosities between his young revolutionary government and the great superpower to the north were already starting to reach a breaking point.

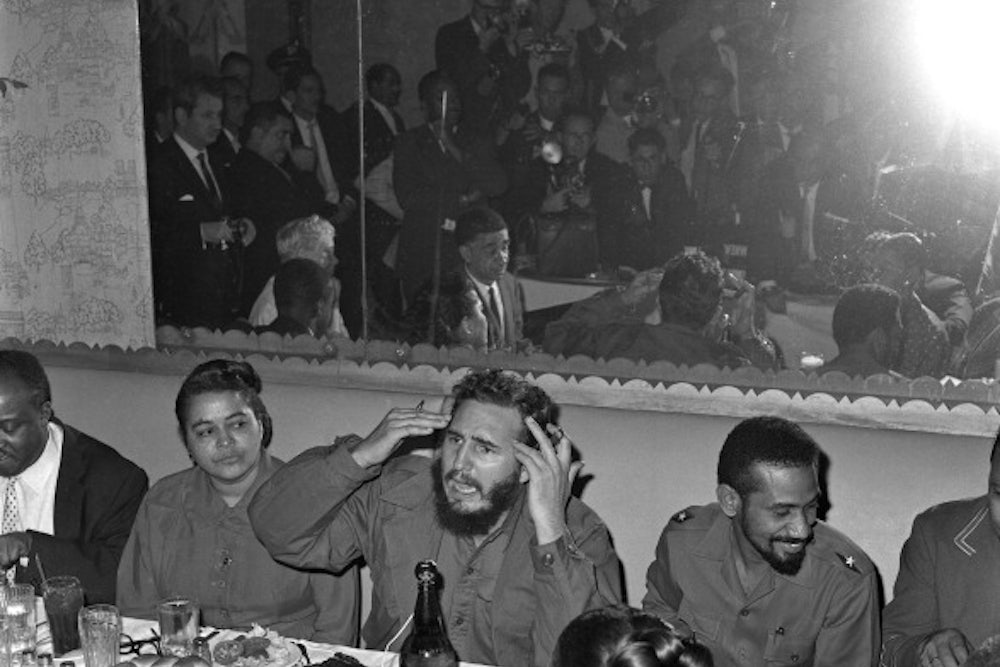

The reception that awaited him the following fall wasn’t nearly so warm. Castro and his bohemian entourage got off to a bad start with management at the elite Shelbourne Hotel, which allegedly demanded an exorbitant advance ahead of the Cuban delegation’s stay. Soon, New York tabloids were circulating reports that these “uncouth primitives” had “killed, plucked, and cooked chickens in their rooms at the Shelbourne and extinguished cigars on expensive carpets.” One subsequent Cuban defector later claimed that Castro had staged the drama. In any case, the Cubans left the Shelbourne, checking in instead at the Hotel Theresa, up past 124th Street in Harlem.

Castro’s decision to relocate his contingent to the heart of black New York quickened the falling out to come and presaged key pillars of Cuban foreign policy over the course of the next half-century: the explicit conflation of Cuban sovereignty with worldwide liberation struggles, particularly in Africa, and the strategic leveraging of U.S. moral hypocrisy in service of revolutionary ideology. Ploy or not, writes historian Brenda Gayle Plummer, the move “constituted a watershed” in U.S.-Cuban diplomacy, “not only because it coincided with a critical juncture in the history of U.S. race relations, but also because it marked a departure in conventional ways of perceiving, and prosecuting, the Cold War.”

To understand what it means for Barack Obama to walk the streets of Havana after all these years, it’s worth recognizing what it meant for Fidel Castro to set up shop in Harlem.

Harlem was a more gracious host to Castro than high-society Midtown had been. Crowds gathered outside the Hotel Theresa, as the honored guest held court in his room. He received official visits from foreign leaders—like Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru—as well as American civil rights figures, such as Malcolm X, New York NAACP President Joseph Overton, and, according to some reports, Jackie Robinson. Juan Almeida Bosque, the Afro-Cuban army commandante, became an instant icon, with throngs of people trailing behind him on the street.

Not everyone was thrilled about the Cubans’ presence. Some 500 Baptist ministers protested their stay. And despite his previous criticism of the U.S. stance toward Cuba, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the congressman for whom the Hotel Theresa’s cross street is now named, felt snubbed by Castro and upstaged by his theatrical visit, warning that Harlem residents were not “dupes” easily manipulated for public relations purposes.

But to the extent Castro’s visit was a calculated, self-serving production, that didn’t negate its deeper political significance. As Plummer, the historian, explains, “Attentions from foreign dignitaries affirmed Harlem’s positive identity at a time when only a few scholars and black nationalists appreciated its history.” Writing for the local Amsterdam News at the time, James L. Hicks commented that, “Though many Harlemites are far too smart to admit it publicly, Castro’s move to the Theresa and Khrushchev’s decision to visit him gave the Negroes of Harlem one of the biggest ‘lifts’ they have had in the cold racial war with the white man.”

This notion that Third World revolutionaries and American civil rights activists were allies in the same essential conflict—that racism and global capitalism were part and parcel of a single oppressive system, presided over by the United States—was a source of tremendous fear in Washington. And the last thing anyone needed was for radical blacks to start getting ideas directly from the Cuban guerrillas. The State Department, having allegedly blackballed them from much of the city’s establishments, took pains to find alternative accommodations for Castro and company once the Theresa had extended them its courtesy. “At that moment, as though by magic,” Castro would later quip, from the floor of the General Assembly, “hotels began appearing all over New York. Hotels which had previously refused lodgings to the Cuban delegation offered us rooms, even free of charge.”

Seventeen countries had joined the ranks of the United Nations that very year, most of them from Africa. Both the United States and Cuba were looking to reach out to these newly freed states, and both recognized racism to be an acute factor at play. In the longest speech ever delivered at the United Nations, Castro transitioned seamlessly from his hotel experience, to the discrimination faced by North American blacks, to the broader evils of “imperialist financial capital” and the “colonial yoke.” (Castro would later add substance to this attention-grabbing profession of solidarity when he sent Cuban troops to fight white supremacist forces backed by the CIA in Angola.) During the same session, the U.S. delegation lamented that “all the explaining and apologies in the world will not erase the injury to an African delegate who is turned away from a restaurant.”

The blatant contradictions of the United States’s position were not lost on American activists. When the embargo of Cuban sugar was offset by an increase in the import quota from Apartheid South Africa the following year, the American Negro Leadership Council on Africa—whose executive board included Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Height, and A. Philip Randolph—brought its objections directly to the secretary of state. Dorothy Day, Bayard Rustin, and Harlem’s own James Baldwin were among those to violate the United States’s ban on food and drug shipments to the Caribbean island. Once relations between the two countries had been frozen, Cuba’s delegate to the United Nations read a statement written by Robert F. Williams—a North Carolina NAACP leader who had visited Cuba and met with Castro in Harlem—demanding that the United States arm southern blacks.

Cuba’s willingness to exploit the United States’s contradictory foreign policy position and domestic racial turmoil helped spur the White House to resort to terrorism and other illegal, covert reprisals against the island nation. It also reinforced the repressive instincts already being brought to bear against American blacks. Ten days after Martin Luther King, Jr. denounced the botched Bay of Pigs invasion as “a disservice … to the whole of humanity” and called on the United States to “join the revolution” against “colonialism, reactionary dictatorship, and systems of exploitation” the world over, the Senate convened a committee investigating Cuban influence on American blacks. As the historian Suzanna Reiss explains in We Sell Drugs, the “narrative of criminality” that would later serve as the foundation for Richard Nixon’s declaration of the War on Drugs simultaneously sought to cast drug abuse as a form of chemical warfare being deployed against the United States by foreign communist forces (and Cuban forces specifically) and to tie homegrown civil rights advocacy to drug use and anti-capitalist “subversion.”

Castro’s accusations of hypocrisy would grow less credible as the civil rights situation improved in the United States and worsened under his regime. But this dynamic never fully went away. America would be more credible in maintaining its posture if it were not, at the same time, supporting far more egregious examples of despotism elsewhere. It would help, too, for a country with the largest prison population of any on the planet, both proportionally and absolutely, to ease up on the pretense that it is targeting Cuba over its abuse of “human rights.” In 1961, reflecting on racial unrest and the deepening conflict with Cuba, Martin Luther King, Jr. predicted that a failure to embody the “revolutionary spirit that characterized the birth of our nation” would leave the United States “with no real moral voice to speak to the conscience of humanity.” Echoing his sentiment five decades later, a Cuban commentator wrote at the height of the 2014 Ferguson protests, “Now, as in times past, we can see the brutal segregation and abysmal inequality for blacks and immigrants, in housing, education, work, [and] public health, among other human rights violations in the so-called most democratic nation in the world.”

And you don’t have to sympathize with the Cuban revolution or its oppressive regime to understand how obstinate hostility towards it has become a diplomatic deadweight for the United States. More than a half-century after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the entire world is united in opposing the embargo. Even the Latin American right, for which the specter of a revolutionary domino effect was once sufficient grounds to perpetrate social cleansing, has come to see political isolation as a counterproductive strategy, undermining the very reforms the U.S. says it would like to see. Obama’s efforts to set relations on a more constructive path have been met with an outpouring of goodwill, for him and the country, but Congress will have to walk down it if the embargo is to be lifted. At this point, alienating Cuba only alienates the United States. Punishing its people damages the United States’s credibility more than the Cuban government’s.