In Philip Roth’s new novel, his alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, alludes in passing to a once famous writer now largely forgotten, whose “sense of virtue is too narrow” for contemporary readers. The writer, no doubt about it, is Bernard Malamud. And what is it that passes for virtue in Malamud? In The Assistant, a grim and slender novel, the Jewish groceryman is eulogized as “a man that never stopped working ... to make a living for his family,” a man who “worked so hard and bitter,” so that for his family there was “always something to eat.” Morris Bober was “a good provider,” the rabbi says, and, “besides,” he was “honest.” He assumed responsibilities. He showed up. He is to be venerated, without exaggeration or ceremony.

It is a narrow sense of virtue, to be sure, and not at all peculiar to Malamud among American Jewish writers. Saul Bellow, too, a provocateur who writes in a racy, unstable idiom and sometimes expresses a venomous antipathy toward the milder emotions, nonetheless swells with admiration for those who show and claim affection, who know, as we used to say, how to behave. “I saw now what I had done,” says the narrator in Bellow’s novella “Cousins”: “treated him with respect, observed his birthdays, extended to him the love I had felt for my own parents. By such actions, I had rejected certain revolutionary developments of the past centuries, the advanced views of the enlightened, the contempt for parents illustrated with such charm and sharpness by Samuel Butler....” Susceptible to the allure of subversive ironies and modern ideas, the Bellow protagonist is still responsive to what he calls “the old thoughtfulness.”

The narrow virtues have often seemed narrow precisely because they were thought to require little thought. Often they have seemed feeble and gray because they were believed to entail no struggle, no weighing of choices. Habit, it is often felt, is the paralysis of spirit. Ordinariness is the negation of virtue. What is dull and dutiful and comes more or less naturally is not to be prized. But Malamud and Bellow (and in this they were not altogether alone) hoped to identify in the ordinary activities available to any decent and thoughtful person, in social ritual and mundane interaction, a stay against the inhuman, against the brutality that ensues in the absence of the quotidian ideals and restraints.

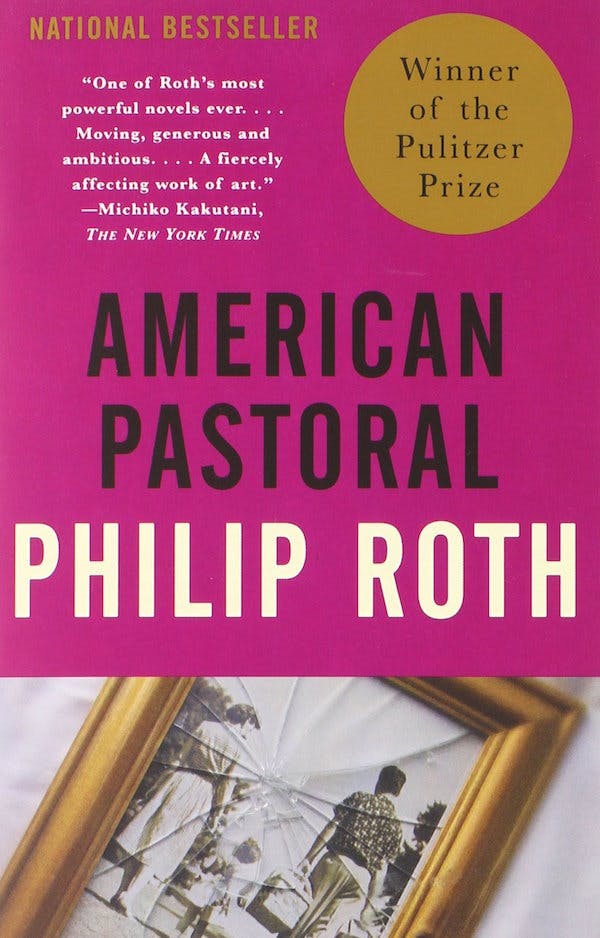

Now Philip Roth engages this possibility. In his new novel, he examines decency, as it is embodied in a good-hearted man whose life seems for a while “most simple and most ordinary and therefore just great.” No reader will be surprised to find that such a life turns out to be neither simple nor just great. No one will wonder at Roth’s ability to show what can become of “ordinary” when an orderly life takes an unexpected turn, or the repressed rears its head, or the good and measured life seems suddenly tedious and intolerable. Roth has for a long time, through many books, developed a powerful and unanswerable subversion of the rock-solid assurances around which many people attempt to organize their lives. He has taught his readers to hold their noses when confronted by pious reflections on “the human condition.” An expert in apostasy and distortion, he has made of his own occasional attraction to moralizing rhetoric an opportunity for savage contradictoriness and wit. His present interest in the ordinary and the virtuous is new in the sense that they now hold him, tempt him, transfixed and bewildered, in a degree not generally discernible in his earlier fiction.

The ordinary man in American Pastoral is an assimilated Jew with an unlikely “steep-jawed, insentient Viking mask” and the youthful attributes of a demi-god. The young Seymour “Swede” Levov is a star athlete worshiped by everyone in his neighborhood in Newark, a large “household Apollo” of an adolescent who goes on from schoolboy fame to marry a Catholic beauty queen, inherit a thriving business, and move his family to a prosperous farm in rural New Jersey. The Swede is ordinary only in the sense that he shapes his life to the measure of the American dream, aspiring to no more and no less than his share of perfection, which is to say, an existence largely without misgiving or menace.

There is nothing ordinary, of course, about the superb physical grace, or the country estate, or the ravishingly beautiful wife, or indeed the temperament of a man who can seem both mild and confident, resourceful and contained. But Roth is most taken with his character’s desire to be ordinary, at ease in his place, without great ambition, without any desire to tear through appearances or to rage against his own limitations. He draws a character who, for all of his success, may be easily condescended to as well-meaning, naive, blandly idealistic, without force—an average man, disappointing, pleasant, natural, displaying no capacity for irony or wit. Surely such a person—some will feel—deserves whatever can happen to him.

The Nathan Zuckerman who narrates American Pastoral, for whom Seymour Levov is an ostensibly remembered person and a character whose life needs to be imagined, is sorely tempted by the prospect of blasting such a life, stripping away every vestige of attractiveness from the character in all of his impeccable generosity and high-mindedness. An early reviewer of Roth’s novel describes Seymour as a puppet, “mounted precisely for the purpose of being ripped,” a figure who exists “to be punished”: for his idealism, his grace and his credulous embrace of the good life. Not exactly. Zuckerman is more than a little bit in love with this fellow. Recently recovered from prostate surgery, impotent and in every way more subdued and more thoughtful than we remember him in previous Roth novels, Zuckerman wonders at the Swede the way one wonders at something moving and peculiar, something that defies explanation.

Still, explanations are advanced. Seymour’s brother Jerry, a cardiac surgeon in Miami, has no trouble summing him up as the man with “a false image of everything,” a man committed to tolerance and decorum, to “appearances” and the pathetic desire “to belong like everybody else to the United States of America.” But this diatribe, it is clear, doesn’t begin to explain Seymour, and the more he is assaulted by explanations and denunciations, and hears himself maligned and diminished, the more securely he remains a wonder, a man astonished to the end at the continuously unfolding spectacle “of wantonness and betrayal and deception, of treachery and disunity” and “cruelty.” Zuckerman wants, like the others, to have done with the crummy goodness of this common man, to dismiss him as a man unable “to understand anyone,” a man without a shit detector, a fraud. But he remains transfixed, somehow admiring and exasperated. Against his better judgment, he makes the man so much more appealing than anyone else he can invent.

Not until very late in the novel does Swede Levov understand what Roth insists that he grasp. “He’d had it backwards. He had thought most of it was order and only a little of it was disorder.” But reality is otherwise. Nothing follows clearly from anything else. Where once there was thought to be cause there is now only chance. A secure home environment can bring forth anything at all. A person blessed with every good fortune may despise her life as surely as a person blasted by fate may remain an optimist. A man with a beautiful wife may be attracted for no apparent reason to a mousy woman deficient in every quality. Those who don’t know these things may be virtuous in one degree or another, but they will not know what life is. That is what Zuckerman would have us accept. That is what Roth would seem also to support. But Seymour’s capacity to arrive at this knowledge in his own way, his capacity for reluctance and suffering, is a part of what makes him a man we can admire.

But American Pastoral is more than an examination of virtue, more than an attack on the delusoriness of liberal good intentions. Roth means it also to be a portrait of America. It moves gracefully from one quintessential American setting to another, from factory floor to rolling hills, from beauty pageant to high-school reunion. Conversations turn on standard American themes, from assimilation to athleticism, from business ethics to sexual fidelity. Characters correspond to familiar American types, including wasp gentry, old-style Jewish liberals, and therapeutic intellectuals armed with fashionably advanced views. Historical markers—the Second World War, Vietnam, Joseph McCarthy, race riots, Weathermen, and so on—routinely identify the public landscape within which Americans of the pertinent generations move. The novel is eloquent in its evocation of vanished American neighborhoods such as Jewish Newark, and it allows characters to be sweetly or fiercely defensive about “what this country’s all about.”

The story line takes many turns, but in essence it is a fairly simple narrative. Zuckerman remembers the Swede, meets up with him late in life, learns what he can about him, and constructs a narrative of the Swede’s life that occupies most of the novel. Seymour is the son of Lou, a prosperous glove manufacturer who looms large in his son’s life until his death at the age of 96. Seymour tries to live the good life in an expensive wasp suburb, but he has to contend with a teenage daughter who develops from elfin companion to tormented stutterer, from antiwar protester to underground terrorist and bomb-throwing killer of innocent civilians.

Merry Levov remains, throughout the novel, a source of enormous agitation and distress for both of her parents. Seymour thinks about her incessantly, rehearsing various episodes in her life and reliving in his imagination all that she does and suffers. He recalls their acrimonious debates and her withering New Left invective. Most especially, he thinks about her setting off a bomb at a local post office and thereby killing an elderly man. He is contacted by a young companion of his daughter, who grotesquely exposes herself to him and offers to lead him to Merry if he will sleep with her. When he learns that Merry has been raped by someone in the terrorist underground, he cannot drive the fact from his mind, he seems almost mad with grieving and pity for his savage little lost girl. Though there are numerous opportunities for the novel to move in for a closer look at the terrorist operation, Roth is satisfied to focus on Merry and her revolting companion, emblems of the ravening ferocity of their kind.

In Merry’s final incarnation, she is a fanatic of non-violence, a Jain who wears a mask over her face to avoid doing damage to delicate micro-organisms in the air. Her father cannot bring himself to turn her in when he has the chance, and he torments himself about what has happened to her, about his responsibility for having produced a monster. Though he cannot abandon his attachment to America and all that it has represented to him, he is sorely tried in his relations with his wife, his brother, and his father—particularly his father, a powerful man who periodically erupts in outbursts of colorful invective against degradation and indecency.

The dust jacket of Roth’s novel promises a work that will take us back “to the conflicts and violent transitions of the 1960s.” It invokes, in Roth’s language, “the indigenous American berserk,” “the sweep of history,” “the forces of social disorder.” It describes, in short, a novel with large ambitions. The narrow virtues celebrated by earlier American Jewish writers were often played out in settings so circumscribed that one could feel the pressure to forget the world and to refine the perspective to a metaphysical essence. But Roth’s novel is absorbed in worldly matters, in history. He wants to know how things happen, how places and events leave their mark on people.

There are instances, here and there, of the profligate extravagance that consumes so much of our attention in novels like Sabbath’s Theater and Operation Shylock, with their verbal energy and their compulsive recourse to every variant of shtick and artifice. But American Pastoral strives mightily to situate its characters in a more classical manner, to insist that their passions are shaped, constrained, and exacerbated by circumstance. It worries about probability and verisimilitude, and it asks, again and again, how this can be and how that can be when reality so manifestly declares what is and what is not allowable. Questions of virtue and responsibility are complicated in this novel by what Henry James called the “swarming facts.” It is not simply that nothing Roth imagines quite adds up; it is that he does not expect the facts to add up, that he supposes reality to lie in their multiplicity, their thickness of texture, their bewildering resistance to dreams of order.

So what is Philip Roth’s America? It is a place where some people work and build and thrive while others fail and destroy and suffer. It is a place where everyone is increasingly aware of vast differences in wealth, and where those who feel guilty about their own successes are increasingly made to feel foolish and irrelevant. It is a place in which radical ideas about fundamental change are held almost exclusively by lunatics and by intellectuals so divorced from fellow-feeling that they can only laugh at deterioration and disaster, “enjoying enormously the assailability, the frailty, the enfeeblement of supposedly robust things.”

There is a side of Roth that likewise revels in the tendency of things to fall apart and to expose the illusoriness of order and optimism. But he is also susceptible to fellow-feeling. Roth appreciates, however reluctantly, the satisfactions that are sometimes generated by those who believe literally in the American dream. When Seymour Levov mourns the Newark destroyed by riots and decay, the Newark “entombed there,” its “pyramids ... huge and dark and hideously impermeable as a great dynasty’s burial edifice has every historical right to be,” Roth invests with weight and dignity the sense of loss for things hard-won and precious. His America, after all, is the place where immigrants not only make fortunes as a result of often despised virtues such as hard work and persistence, but in which those same immigrants often bring forth children endowed with vision and compassion.

It is possible, of course, to suppose that what Roth calls “the indigenous American berserk” has more to tell us about the country than the stories of immigrant success and the building of viable political institutions. Or at least it may tell us what Roth himself regards as fundamental to the American spirit: a propensity to violence, conspiracy, and irrationality. This propensity is not at all times and places obvious. Americans are adept at convincing themselves that it is a limited propensity, that it belongs to lunatic fringes that cannot in the long term threaten our collective commitment to reasonableness and tolerance. Yet Roth seems to believe that violence and irrationality are never very far from the surface of American life, that we deny it at our peril, and that our optimism is purchased in the way the individual purchases tranquillity, through repression and willful blindness. The daughter of Seymour Levov is not simply a lunatic. She is to be understood, insofar as we may presume to understand her, as an important expression of our collective unconscious. If this is not easy to accept, any more than we would find it easy to accept, say, that the Bader Meinhof gang in Germany or the Red Brigades in Italy expressed the deeper selves of the societies they terrorized, well, as the novelist would seem to say, there it is.

Merry Levov is Roth’s exemplification of our impatience with limits, our hatred of the gradualism and the decorum that we profess to prize. As an adolescent growing up in the first days of the Vietnam War, she finds her opinions confirmed by her parents and her grandfather, but she grows impatient with their support. Like other young people involved in antiwar activities in the ‘60s, she finds a way to turn the epithet “extreme” against her own family, as in: “No, I think extreme is to continue on with life as usual when this kind of craziness is going on ... as if nothing is happening.” Those who are opposed to America’s involvement in Vietnam must bear witness—so she insists—by turning against their own comfortable lives, if necessary by throwing bombs. Just so, those who profess concern for black people going to pieces in urban ghettos must refuse to persist in business as usual, must refuse to insist upon profits, even if their refusal should cause their factories to fail and jobs to disappear. The worst is not to be feared if it may be a prelude to drastic change. The American berserk, as embodied in the figure of Merry Levov, is associated with ideas that were pervasive in the ‘60s, and it is in part the burden of American Pastoral to suggest that these views really do express an important feature of American life.

The strangest thing about all of this is that Merry Levov never emerges in this novel as anything but a pathetic figure. As a child she is appropriately lovable and childish, but she rapidly grows into a fearful thing, twisted and angry, a caricature of herself. She becomes a type. She is, in fact, precisely the type pilloried by those critics for whom opposition to the Vietnam War and participation in the civil rights movement were mainly psychological expressions, the work of rebellious adolescents acting out their mostly impotent rage against authority. This tendency to reduce the movements of the ‘60s to an undifferentiated cartoon of adolescent rebellion is given new life in Roth’s novel. By contrast, writers such as James, Conrad and Vargas Llosa, in their novels of politics and society, mounted a savage attack on bomb-throwers and ideologues while permitting them their misguided idealism and a sometimes adult grasp of power and injustice. To place Vargas Llosa’s wild-eyed Alejandro Mayta alongside Merry Levov is to appreciate at once the dignified passion for radical renovation that the Peruvian novelist permits his character and the utter puerility and one-dimensionality of the American novelist’s radical figures.

That Merry Levov is depicted as something of a lunatic is not especially objectionable, for it is surely true that there were lunatics and obsessives in the radical movements of the ‘60s. But she and her more luridly drawn companion are, in Roth’s novel, the primary exponents of oppositionist and critical views. The conditions that aroused so many mature adults to participate in the antiwar and civil rights movements are barely mentioned in a book committed to examining the period. For American Pastoral, recent American radicalism is to be associated with irrationality and the unconscious. In fact, it was both more dangerous and less dangerous than that. There is no effort in Roth’s novel to link it to the genuine tradition of American radicalism that goes back at least to Emerson and Thoreau and, in this century, to Randolph Bourne, Paul Goodman and Bayard Rustin. Merry Levov and her companions in extremism are all we need to know, apparently, when we come to consider what blasted the social order.

The failure of Roth’s novel, in this respect, is quite considerable, however unmistakably particular passages are the work of a master. If there is such a thing as the indigenous American berserk, then surely it must entail a good deal more than a lunatic fringe largely limited to deranged adolescents acting out fantasies of retributive violence. And if these adolescents, who usually grow up into pinstripes, tweeds and cappuccino bars, can be so readily dismissed and condescended to by their elders, including Nathan Zuckerman, then how can they be said to represent an enduring and significant feature of American life, a tendency to which even the best of us are regularly susceptible? This novel wants to have it both ways. It wishes to develop an apocalyptic vision of the real America, the underside of our characteristic optimism and bland goodwill, but it wants also to propose that what we refuse to acknowledge in our pusillanimous American selves is pathetic, adolescent, laughable, and decidedly marginal, however terrible the occasional consequences associated with this “other,” truer reality.

Consider Roth’s presentation of the facts involved in the destruction of Newark. The dominant perspective belongs, more or less equally, to Zuckerman, to the Swede, and to his father. According to them, there was once a “country-that-used-to-be, when everyone knew his role and took the rules dead seriously, the acculturating back-and-forth that all of us here grew up with.” Of course there were conflicts in that once-upon-a-time land, but they were usually manageable, they conformed to something about which you could make some sense. And Newark was very much a part of the “country-that-used-to-be,” a place where pastoral visions may not always have been easy to come by, but where “the desperation of the counterpastoral” was also not much in evidence.

In Roth’s reasonable Newark of Jewish and other immigrants, there are factories and businesses that produce well-made goods and turn reasonable profits. They employ people “who know what they’re doing,” who are pleased to do good work and more or less content with what they are paid. At least they do not complain. They are loyal to their employers, and they may well remember gratefully how things have changed for the better since the bad old times 100 years earlier when factories were places “where people ... lost fingers and arms and got their feet crushed and their faces scalded, where children once labored in the heat and the cold....” The factory owners are also apt to have a vivid sense of their own origins, to remember working “day and night” and living in intimate contact with working people at all levels of manufacturing and selling. Their stubborn celebration of everything American has much to do with how well things can go when people believe in the system and rely on each other.

Given this account of reality, it is no wonder that the eruption of civil strife in the ‘60s should seem so incredible not only to the Levovs but, apparently, also to Zuckerman. The nostalgia for the “country-that-used-to-be” is so palpable in this novel that it virtually immobilizes the imagination of reality and leaves the reader susceptible to a rhetoric for which the deteriorating urban landscape is a “shadow world of hell” and predatory blacks roaming the Newark streets are part of a “surreal vision.” Once, not long ago, according to this narrative, everybody had it good, or good enough. But many Americans suddenly went unaccountably crazy, and what “everyone craves” came to pass, “a wanton free-for-all” in which what was released felt “redemptive, ... purifying, ... spiritual and revolutionary.” However “gruesome” and “monstrous” what followed, something real happened in Newark, something irresistible and deeply implicated in the American grain.

So we are to believe. Though the Levovs watched with horror, and deplored, and most other Americans presumably recoiled as well, we are asked to accept that somehow “America” spoke its deep, revealing truths in the intoxication of riot and mayhem. We are also asked to accept, as befits this pattern, that those who set the cities on fire, who beat on “bongo drums” while their neighbors looted and sniped and left behind a “smoldering rubble,” were actually in flight from the good life. We are to accept—so the logic of the novel dictates—that the blacks of the inner city must have been incomprehensibly dissatisfied with their wonderful jobs and turned on by the prospect of liberating something vital and long buried in their otherwise admirable lives.

The problem is, Roth’s book offers us no way to think about such a view of things. Its elegy for the dead city and its old ways is affecting, but it is also disconnected from anything like a serious account of what the old ways actually entailed, and what were the varied motives and desires of the inner-city residents who were caught up in the destruction of their own communities. To read Roth on the Newark riots is to suppose that just about everyone participated in the looting and the carnage, and that no one can have had good, concrete reasons for loathing the conditions in which they lived. To understand the ‘60s is, again, to invoke individual and group psychology, to refer to something deep and peculiarly American, to deplore what happened while at the same time suggesting that it had to happen and cannot be accounted for by citing social, political or economic factors.

Roth’s novel is finally not an adequate study of social disorder. It does not tell us what we need to know about America, what a novel can tell us about the complex attitudes and allegiances of a time and a place. It laments the denial of reality on the part of middle-class suburbanites such as Seymour Levov, while offering as the alternative to illusion “surreal” and “grotesque” eruptions such as few Americans are likely to encounter. It sets up as representative figures of disorder and “reality” persons who are mad, and whose attachment to disorder is so pathological that they make it impossible for us to consider seriously the actual sources of discontent in American society. When violence breaks out in this novel, it seems more like an inexplicable convulsion than an expression of feelings shaped by complicated individuals responding to the actual conditions of their lives.

And yet Roth’s interest in an idea of simple virtue is an impressive achievement. For if the world, as he understands it, is a place of chaos and contradiction, in which order is fragile or even illusory, then virtue, too, may seem like a figment of someone’s wishful thinking, a willed fantasy with nothing to sustain it. But Roth finally suggests that it is not. Like the rest of us, he wonders what virtue can be worth when it is rarely effectual in worldly terms. And he refuses to allow goodness to sweeten anything, to distract him from what we are and what we do. Yet his triumph in American Pastoral is the portrayal of persons who are unmistakably good and genuine. They understand no better than he does what to make of events that astonish and assault them, but they do not give up on their sense of how to behave.

Seymour Levov is no paragon of perfect virtue, and his father can seem shrill and forbidding in his vehemences. But these are men who continue to display thoughtfulness, however much reason they have to be disappointed and to flee in bitterness from the decencies that make them seem irrelevant to their contemporaries. The father may have absurd ideas about how to deal with disorder—“I say lock [the kids] in their rooms”—but he is strangely appealing in his insistence that “degrading things should not be taken in their stride.” That is right. And the son, who suffers greatly, who does not know enough, who takes “to be good” everyone “who flashed the signs of goodness,” retains in Roth’s hands the capacity to be appalled—not thrilled, but appalled—by transgression, to be tormented by the spectacle of needless suffering, and to think, ever to think, about “justification” and “what he should do and ... what he shouldn’t do.” His humanity is intact. And it is, Roth seems to be saying, the only thing we can rely on.