Thanks to Donald Trump, the specter of class war is haunting the Republican Party. But this isn’t a traditional class war wherein the masses overthrow capitalism. Instead, it features the poor and the working class destroying the country-club establishment.

In response to Trump’s successful use of populist rhetoric (although rarely populist policies) to woo less well-to-do Republicans, some conservative intellectuals have taken the curious tack of wholesale condemnation of the working class. In a widely discussed article in National Review, Kevin Williamson argued that it is wrong to believe that

the white working class that finds itself attracted to Trump has been victimized by outside forces. It hasn’t. The white middle class may like the idea of Trump as a giant pulsing humanoid middle finger held up in the face of the Cathedral, they may sing hymns to Trump the destroyer and whisper darkly about “globalists” and—odious, stupid term—“the Establishment,” but nobody did this to them. They failed themselves.

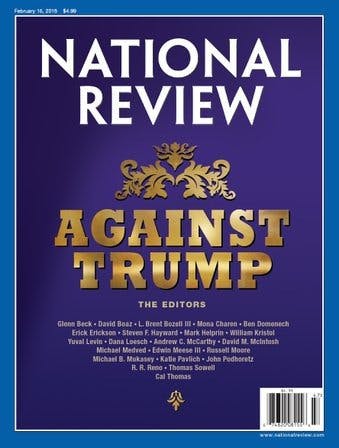

National Review has been struggling mightily to convince Republicans not to nominate the real estate mogul, going so far as to publish an entire issue devoted to the cause, “Against Trump.” But if Williamson’s article is part of National Review’s larger persuasive agenda, it seems like a singular misstep. After all, you rarely win people over by telling them that all their woes are their fault.

However, Williamson’s argument that the white working class “failed themselves” makes more sense if we place it in National Review’s intellectual lineage. The magazine was founded as the organ of a distinctively aristocratic conservatism, one that in the early days never concealed its scorn for ordinary people. In recent decades, that aristocratic conservatism has sometimes been obscured by a populist mask, but under the pressure of Trumpism, National Review is showing its true face.

To understand National Review, we have to go back to its founder William F. Buckley Jr. In 1944, while training to be an officer in Camp Wheeler, Georgia, Buckley found that he could barely contain his contempt for most of his fellow soldiers. The son of an oil magnate, Buckley had been raised in great wealth and had attended Andover. The army was full of people he had rarely encountered before. According to biographer John Judis, Buckley “found it difficult to share quarters with men of inferior manners and intelligence.” In a letter to a colonel, Buckley said that while “some” of the noncommissioned officers were fine men, others were “crude, course, vulgar, and highly objectionable.” Told by a platoon leader that condoms were available for soldiers on leave, Buckley priggishly insisted that he, for one, didn’t need them—the implication being that he was better than the fornicating riffraff that surrounded him. According to one of his colleagues, Lieutenant John Lawrence, Buckley had a “definite air of superiority which alienated a tremendous number of people.”

Buckley’s difficulty fraternizing with the men wasn’t just a product of his personality, but also his full-fledged ideological commitment to aristocratic conservatism. Buckley had been much influenced by the elitist teachings of Albert Jay Nock, a family friend who spent much time at the Buckley estate in Milford, Connecticut. Nock believed that the masses were “structurally immature” and that democracy was an “ochlocracy of mass-men led by a sagacious knave.”

Buckley never lost his Nock-influenced disdain for democracy, and his biggest intellectual disappointment was that he was unable to finish a magnum opus titled Revolt Against the Masses, which would show the merits of elitist objections to egalitarianism. It was no accident that Buckley liked to keep company with European aristocrats like Erik Maria Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, who often argued in the pages of the magazine for monarchism. Another Buckley crony was Otto von Hapsburg, pretender to the Austrian throne, who said National Review was the only magazine that talked sense to the American people.

To be sure, as the conservative movement gained ascendancy, Buckley learned to disguise his aristocratic agenda with a veneer of populism. He was helped in this task by his Yale mentor Willmoore Kendall, a highly eccentric political theorist who used the ideas of Rousseau to justify the politics of Joseph McCarthy and Barry Goldwater. But the occasional populist arguments Buckley would make were barely even skin deep. Indeed, his entire public persona was based on an appeal to the idea of elite leadership. With his pretentious vocabulary, drawling accent, frequent yachting, and frequent ski trips in Switzerland, Buckley was a pseudo-aristocrat who led a movement of those who thought they were better than the rest of America.

The best way to understand Kevin Williamson’s article is that it is a return to the aristocratic conservatism of Albert Jay Nock, to a belief that the world is divided into two irreconcilable camps: the few who embody civilization and excellence and the many who are “structurally immature.” The few owe nothing to the many. If the many want to improve, they have to hoist themselves up by individual effort to a place at the table with the few.

This stark social Darwinism is clear in the closing paragraphs of Williamson’s piece, which deserve to join the Nockian pantheon of contemptuous attitudes towards the masses:

If you spend time in hardscrabble, white upstate New York, or eastern Kentucky, or my own native West Texas, and you take an honest look at the welfare dependency, the drug and alcohol addiction, the family anarchy—which is to say, the whelping of human children with all the respect and wisdom of a stray dog—you will come to an awful realization. It wasn’t Beijing. It wasn’t even Washington, as bad as Washington can be. It wasn’t immigrants from Mexico, excessive and problematic as our current immigration levels are. It wasn’t any of that.

Nothing happened to them. There wasn’t some awful disaster. There wasn’t a war or a famine or a plague or a foreign occupation. Even the economic changes of the past few decades do very little to explain the dysfunction and negligence—and the incomprehensible malice—of poor white America. So the gypsum business in Garbutt ain’t what it used to be. There is more to life in the 21st century than wallboard and cheap sentimentality about how the Man closed the factories down.

The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserve to die. Economically, they are negative assets. Morally, they are indefensible. Forget all your cheap theatrical Bruce Springsteen crap. Forget your sanctimony about struggling Rust Belt factory towns and your conspiracy theories about the wily Orientals stealing our jobs. Forget your goddamned gypsum, and, if he has a problem with that, forget Ed Burke, too. The white American underclass is in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles. Donald Trump’s speeches make them feel good. So does OxyContin. What they need isn’t analgesics, literal or political. They need real opportunity, which means that they need real change, which means that they need U-Haul.

The upshot of Williamson’s article is that some conservative intellectuals have given up trying to persuade the unwashed masses in their party. Nock wasn’t interested in practical politics. He preached a monastic retreat into high culture, where a “saving remnant” of the elite could rescue civilization from the barbarians. That’s the logical conclusion to draw from Williamson’s article as well: The poor are beyond saving, and all that is left to do is shower them with contempt.