Stately brick buildings. Immaculately mown lawns. Students walking down the pathways, carrying their books and papers. A quaint Main Street, with a bookstore, a coffee shop, and an inexpensive pub. Welcome to College Town, USA.

As Bernie Sanders tries to kindle a political revolution to defeat Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination for president, it’s places like this where he must catch fire. Young voters are a critical part of his coalition; in five states, he has won over 80 percent of the 17-to-29-year-old vote. And college campuses have long been amenable to the kind of unapologetically liberal politics Sanders espouses.

In many university towns, Sanders has indeed dominated. He won 60 percent of the vote in Johnson County, Iowa, where the University of Iowa is located. In Western Michigan University’s Kalamazoo County, he took 61 percent. In the home county of Colorado State, he bested Clinton 67 percent to 33 percent.

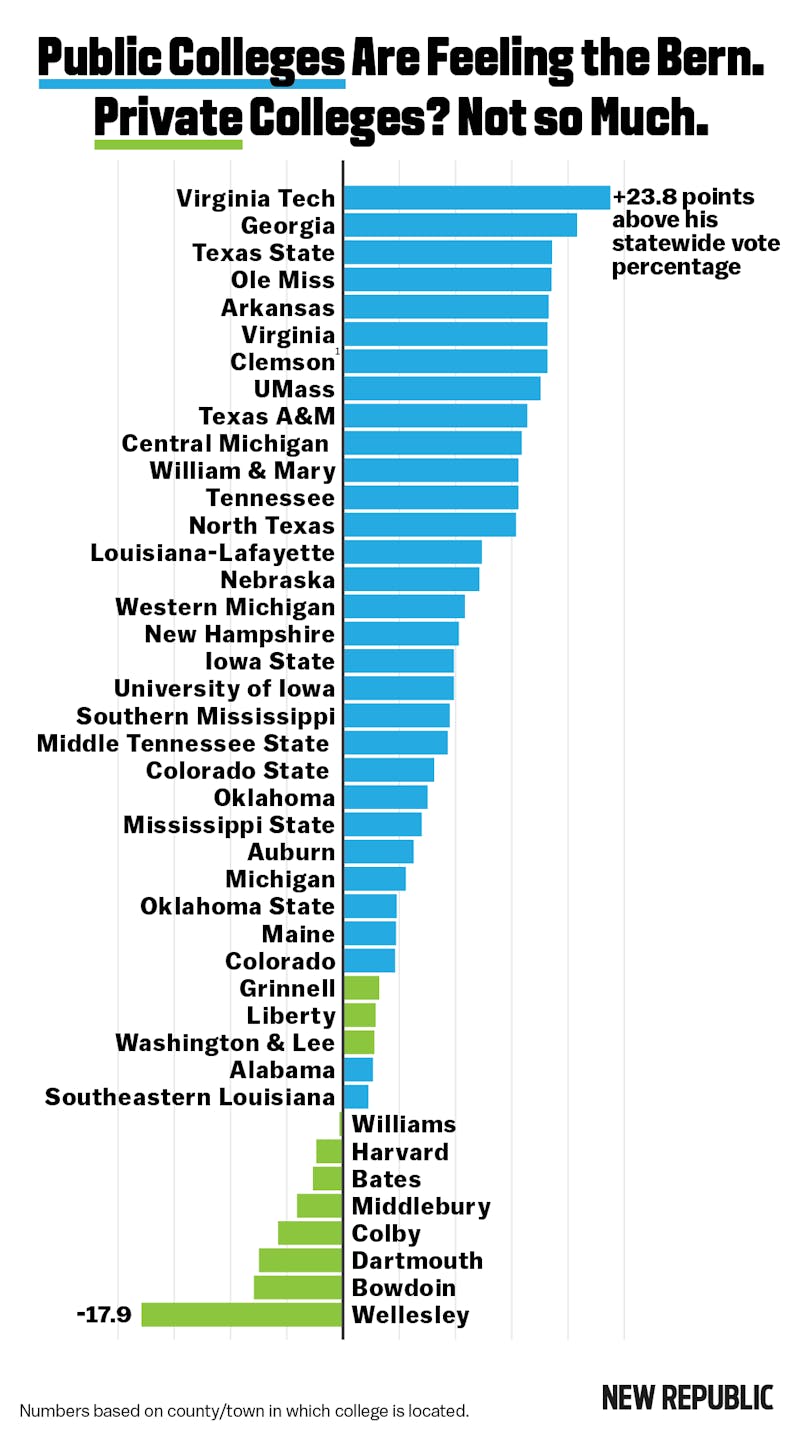

Even in states where Sanders has lost handily, he has done well in bookish burgs. He won the home localities of University of Virginia and Virginia Tech despite losing Virginia as a whole by almost 30 points. He improved upon his Georgia performance by 21 points in the University of Georgia’s Clarke County. And in the county surrounding Texas A&M, he did 16 points better than his statewide haul.

But not every college town is feeling the Bern, complicating his reputation as the candidate for young, highly educated liberals. Sanders has also performed poorly in places where you would expect his message to resonate. For instance, he lost Cambridge, Massachusetts—nicknamed “the People’s Republic of Cambridge” by the liberal Harvard and MIT students who inhabit it—53 percent to 46 percent. His share of the vote in Brunswick, Maine, where Bowdoin College is located, was eight points below his statewide average. In Dartmouth’s Hanover, New Hampshire, he underperformed by seven points. What’s going on here?

More than 40 cities, towns, or counties that are known primarily as university communities have voted in the Democratic primary so far this cycle. They’ve given Sanders anywhere from 82 percent to 22 percent of the vote—or, in relative terms, they have ranged from beating his overall performance in the state by 24 points and trailing it by 18 points. There is no correlation between his percentages and the broader demographic factors that explain his support nationwide, such as median household income or education level. His raw performances do correlate slightly with racial diversity, but only because Sanders does well in relatively white states and worse in states with a large minority population. Race has no effect on whether Sanders over- or underperforms his statewide numbers in college towns.

The variation could be regional. As is apparent from the examples above, Sanders does poorly in college towns in the Northeast and well elsewhere. New England election results are also reported by city or town, whereas in most other states the results are for a university’s entire county. But that’s not it either. Though Sanders flopped in Cambridge, he excelled in Amherst, Massachusetts, running 18 points better in and around the flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts than he did statewide. The University of Maine’s hometown, Orono, also gave Sanders a boost. And in the backyard of the University of New Hampshire, he overperformed by 10 points, winning the town of Durham with 71 percent of the vote.

One explanation that does fit the data is prestige. Sanders loses ground around elite liberal arts colleges and Ivy League universities; he gains around large, less exclusive schools. But there are still exceptions. Sanders received a 16-point boost in Williamsburg, Virginia, home of the well-regarded College of William and Mary. He took an above-average 55 percent of the vote in Washtenaw County, where the University of Michigan is proudly referred to as the Harvard of the West. These examples point to a more precise pattern: Sanders does well in college towns affiliated with public universities. Clinton does well in college towns surrounding private institutions. The correlation here is almost perfect.

A prominent part of Sanders’s platform might account for the split. He has been alternately praised and ridiculed for his plan to provide “free college”—specifically, free tuition at all public universities. It stands to reason that this proposal holds greater appeal among public-school students sick of paying their bills every semester than those at private schools, for whom it wouldn’t make a difference.

But it probably also represents a deeper phenomenon. Sanders doesn’t just hold steady in private-college towns—Clinton actually eats into his support. In all likelihood, this has less to do with the students and more to do with the professors and administrators. The well-off, uber-educated communities around Wellesley, Middlebury, and their ilk are the very definition of elite—socially, intellectually, and economically. And when elites lean to the left—as academics often do—they are the spitting image of the Democratic Party establishment. Clinton, of course, is the strong preference of this establishment, so it makes sense that she would do well in their hometowns.

There are important lessons here for election watchers, as well as both campaigns. In North Carolina and Ohio, Sanders can look to communities like Chapel Hill and Athens as places he can run up the score. But don’t be surprised if Clinton wins the votes of the Duke Blue Devils or Oberlin Yeomen. The revolution, it seems, has its limits even in that supposed incubator of radical thought, the university.