On a Friday in April 2012, police officers arrived at a small public school in Milledgeville, Georgia. They were there to arrest a black female student for assaulting a principal and damaging school property. The girl in question was placed in handcuffs, brought to the police station, and charged with battery and criminal damage to property. Her name was Salecia Johnson. At the time, she was six years old.

Johnson’s arrest made national headlines and, while the charges were dropped, she was suspended until the start of the next school year. A school superintendent defended the school’s actions, calling Johnson’s behavior “violent and disruptive” and stated that the police were called out of “safety concerns.” The police reaffirmed this claim, asserting that Johnson was placed in handcuffs for the safety of other students as well as her own. In the local paper, an op-ed was published in which the author called the child’s actions “a dangerous display of uncontrolled anger/rage.”

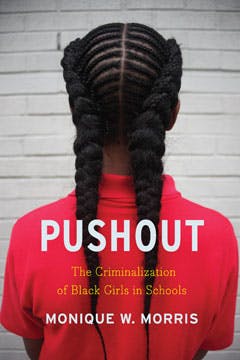

In her new book Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools, Monique W. Morris argues that highly publicized cases like Johnson’s are only fragments of the widespread oppression black girls face in the American educational system. It’s a subject frequently overlooked in today’s conversations about racism and the school-to-prison pipeline, which focus on the plight of black men and boys. What this means, Morris explains, is that “the sometimes similar but frequently not so similar ways that Black girls are locked out of society become lost.”

The legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” almost 30 years ago, in response to anti-discrimination law that did not allow black women “to combine their race and gender claims into one”—leaving them unprotected from much of the discrimination they encountered. Crenshaw more recently defined the term as an “analytic sensibility, a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power,” whether that identity is gender, race, class, or sexuality. Other scholars, such as Nikki Jones and Brittney Cooper, have employed this sensibility to better understand the challenges that black women and girls face. In writing Pushout, Morris, a social justice scholar, adds to this discourse by exploring the specific ways that black girls are pushed out of our country’s schools.

From 1973 to 2010, the number of secondary students who were suspended or expelled rose by nearly 40 percent. There has been a great deal of research exploring the impact of “zero-tolerance” policies on black boys, but the consequences for black girls have been studied far less. And yet, according to the African American Policy Forum (AAPF), while black boys are the group most likely to be suspended from school, black girls have a higher relative risk—six times higher—of suspension in comparison to their white female counterparts. In New York City in 2012, 53 black girls were expelled, while no white girls were. And, according to Morris, while black girls represent 16 percent of female students, they represent almost half of all girls with a school-related arrest. Punitive policies, such as suspension and expulsion, are linked to school dropout and increased contact with the justice system, affecting these girls socially and economically for the rest of their lives.

So why does this happen? First off, Morris notes that

schools—unless they intentionally attempt to reverse these trends—often reflect

the oppressive norms of society at large. These are the types of norms through

which someone could see the temper tantrum of a black six-year-old girl as

violent and dangerous. They also contribute to stereotyping that frames black

girls as “sassy,” “ratchet,” and “defiant”—so much so that black girls often

get labeled by their teachers as disruptive and disrespectful simply for asking

questions in class. “I always question. And then sometimes, teachers get mad

off of that,” one girl told Morris. “They say I’m disrespectful. That’s my label.”

Black girls also aren’t simply allowed to be girls. It’s a phenomenon that Morris describes as “age compression,” in which black girlhood is conflated with black womanhood. The reasons for this are complex, but Morris notes that the hyper-sexualization of black females has been a constant, dating back to historic stereotyping of black women as “jezebels” with loose morals, an idea that was once used to justify the rape of slaves. In interviews, black teenagers tell Morris about how they are seen by others as much older than they actually are, leading to daily sexual harassment and abuse. One girl stated that she felt like, “No matter what a Black girl do, no matter how small she is or how big she is, a man is going to always look at her sexually.” This can lead to simple injustices in the classroom, such as black girls being sent home for wearing clothing that is “too promiscuous” even if their white counterparts are wearing the same exact thing. But it also lends itself to much more serious problems, such as teachers blaming girls for cutting class in situations where they are failing to show up because they are being prostituted or sexually exploited.

Unsurprisingly, black girls are also overrepresented in the juvenile justice system (representing 33 percent of detained female youth, but only 14 percent of the general population), where Morris characterizes classroom environments as “hyperpunitive.” The girls Morris interviews describe the schoolwork as repetitive, uninspiring, and often below their skill level; in the juvenile court school they attended, all the girls were educated in a single classroom, despite their differing ages and grades. As one girl put it, “School here’s really frustrating for me. The teachers here know that we’re here temporarily, so I feel like they don’t make sure that we’re really learning.” Rather than helping the girls get back on track, correctional education pushes them even further behind.

Many of these problems come back to the teachers, administrators, and correctional officers in these girls’ lives whose reflexive instinct is to control and surveil, rather than to stop and listen. Some of these girls do lash out in class but, usually, they are children who have been hurt in some way or another. As Morris repeatedly points out, “People who have been harmed are the ones who harm others.” The girls who Morris talks to relate feelings of being disrespected and ignored, and some disclose experiences of struggling with gender transitions, disabilities, poverty, and sexual abuse.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Rather than serving as a reflection of our society’s punitive policies, schools can instead be a force for reversing these trends. It is arguably their very purpose—education, after all, is supposedly the great equalizer. Morris describes one school, which she nicknames Small Alternative High, where teachers are instructed to work hard to listen to their students and diffuse situations that might escalate. The school itself also has a flexible schedule, which helps students struggling with problems in their personal lives to stay enrolled and complete their credits. The AAPF report recommends a set of policies for schools and administrators, such as training teachers to recognize the signs of sexual abuse, revising protocols that funnel girls into the juvenile justice system, and expanding programs for girls who are pregnant or parenting. It also calls for a greater recognition of black girls in meaningful ways, such as in policy research, program funding, and advocacy. A recent White House report, Advancing Equity for Women and Girls of Color, also suggests increasing access to inclusive STEM and career technical education.

We need look no further than the movement for police reform to see how issues of intersectionality can, and should, be integrated into policy debates. Black Lives Matter, a movement that originated with three women, has pushed racial justice to the forefront of the Democratic primary campaign, where it would have otherwise lingered on the sidelines. The movement initially started in 2013, after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, but has evolved since, shifting focus to pay special attention not only to the black men affected by institutional racism, but to black women, including trans and queer women, as well. When activists interrupted Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley at Netroots Nation last July, they weren’t just shouting “black lives matter”—they were also shouting “say her name,” referring to the women—Sandra Bland, Mya Hall, Alexia Christian—who had so quickly disappeared from national memory after their deaths.

While Morris acknowledges the need for better policy, she ends her book with a different appeal. One that, if this were a piece of fiction, or a book on a different topic, would seem banal. It’s not. She argues that “countering the criminalization of Black girls requires fundamentally altering the relationship between Black girls and the institutions of power that have worked to reinforce their subjugation.” To put it more simply, it requires a system that cares about these girls. As one girl told Morris, “I just need … [someone to ask], ‘How are you doing with school?’” The only way to do this, and to begin fixing the school-to-prison pipeline, Morris writes, is to love our black girls like they matter.