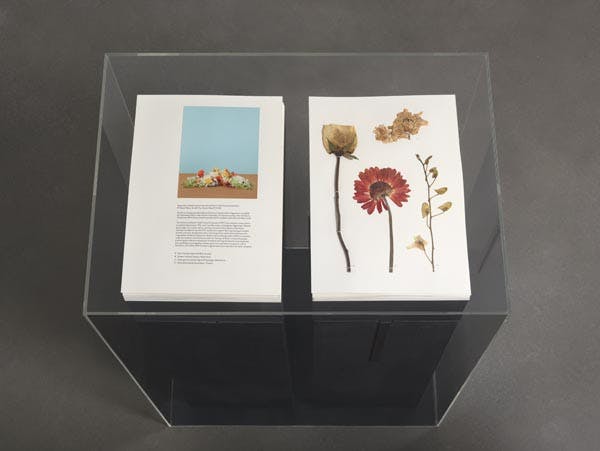

Around 1:30 am on September 30, 1938, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, along with the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain and the French prime minister Édouard Daladier, signed a paper that handed over a swatch of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany. A photograph from the night’s negotiations shows Mussolini, Hitler, a German translator, and Chamberlain sitting uncomfortably in stately armchairs around a large, reflective table, in the middle of which, placid and unassuming, rests a floral arrangement.

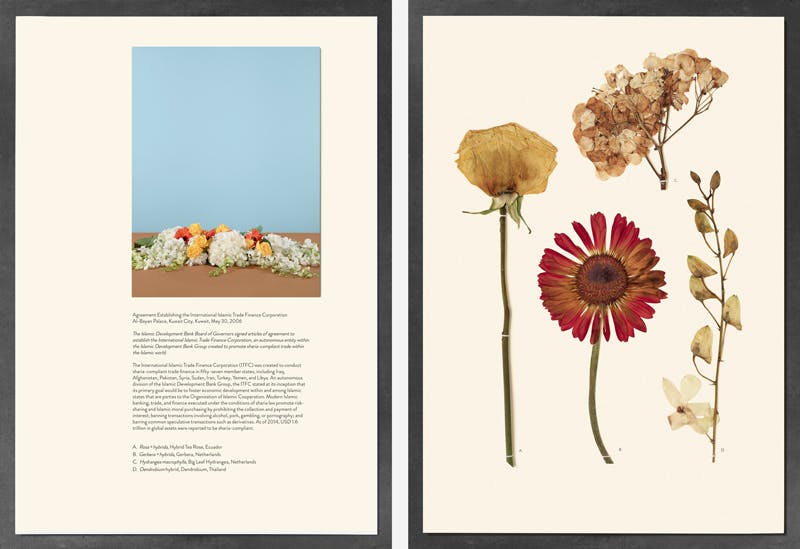

These flowers, surrounded by men who would drive the world to war, inspired the latest exhibition by artist Taryn Simon, Paperwork and the Will of Capital, which includes vivid recreations of the floral arrangements that served as silent witnesses to the signings of 36 international agreements between 1968 and 2014. For the exhibition, currently on view at Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea, Simon restaged the bouquets and photographed them against two-tone backgrounds, drawing on the color schemes of the original ceremonies. She then dried the flower specimens, sewed them to herbarium paper, and placed the pages in black concrete presses that litter the main room of Gagosian. Encased in glass boxes and looking impossibly heavy, the presses evoke podiums and columns, two standard trappings of statecraft.

It is the clinical and brilliantly

colored photographs of the flowers that hold the floor, however. In one, an

arrangement of lipstick-red anthuriums, magenta dendobriums, mustard Mokara

orchids, and pale pink Hybrid Tea Roses erupts against a bifurcated sea green

and mustard background. The bouquet’s source: Australia’s agreement on September

26, 2014 to pay Cambodia $40 million AUD in exchange for permanently resettling

some of the refugees and asylum seekers it had been detaining offshore. In

another photograph, two startling lobster claws seem to emerge like ballet

dancers from a pile of beige cymbidiums against cool shades of blue. The image represents

FIFA’s decision to outlaw third-party ownership of soccer players’ economic

rights, an agreement that was also, coincidentally, signed on September 26,

2014.

On their own, the photographs give none of this information away; they are big, beautiful, and matter-of-fact. This is very much in keeping with Simon’s style, presenting objects and people head-on against neutral backgrounds to invest the pictures with an aura of objectivity. As in Simon’s Contraband, which records five days’ worth of seized items at Kennedy Airport, the photographs of Paperwork and the Will of Capital are both self-evident and enigmatic.

Unlike many contemporary art photographers, who believe description to be the province of press releases, Simon has long accompanied her work with texts that are essential to the art they elucidate. They are often as straightforward as her pictures, written with an air of authority and order, even as they recount stories of chaos or absurdity. In Paperwork and the Will of Capital, each photograph is accompanied by a panel summarizing the treaty, along with a list of the flowers used and the countries they came from—flora which rarely, if ever, corresponds to the nations doing the politicking. The panels are inset into the right side of the mahogany frames; the effect summons up margins in a book or push panels on doors, as if, through the information they offer us, the artworks were portals.

The relationship between text and image in Paperwork and the Will of Capital is jarring. Tales of ineffectual attempts to rehabilitate the Lebanese postal system, communiqués demanding the repatriation of cultural artifacts, threats of spilling “Egyptian blood” over the building of a dam in Ethiopia, Ronald Reagan’s authorization of covert CIA action in Afghanistan—all are contrasted with lovely, harmless-looking flower arrangements. Simon’s work thrives on juxtaposition, taking shape in the “invisible space between a text and its accompany image,” as she explained in a 2009 TED talk. “At best the image is meant to float away into abstraction and multiple truths and fantasy, and the text functions as this cruel anchor that kind of nails it to the ground.”

What saves Simon from didacticism is that her texts don’t function as straightforward captions. The texts describe political events that are related to, but not actually represented by, the flowers. There are leaps of interpretation required to connect one to the other. Simon first had to source archival images of the original meetings, placing her faith in the authenticity of photographs. (Something her 2002 series The Innocents, which depicts people who served time for wrongful convictions, warns us not to do). She then asked a botanist to identify the flowers, introducing another degree of uncertainty. Next, she recreated the bouquets and photographed them isolated in new settings—leaving us with traces that index not the original events they’re meant to stand in for, but the restaging of small pieces of them. She took the illusion one step further by drying and preserving the flower specimens, creating more traces of what amounts to a series of historical reenactments.

These complications are compounded by the fact that all of the arrangements are what’s called “impossible bouquets,” meaning they’re collections of plants that could never be found growing in the same place at the same time—man-made flower fictions. Alongside such elaborate constructions, which appear deceptively simple, Simon has placed accurate descriptions of political events that were set in motion at the original, photographed meetings. We are looking at evidence of a kind, but it is ex post facto.

Traditionally, when a photograph is paired with text, “together the two then become very powerful; an open question appears to have been fully answered,” art critic John Berger once wrote. Yet Simon tries to resist that simple equation. In all of Simon’s work, and especially in Paperwork and the Will of Capital, “there is no end result,” to borrow the artist’s own words.

If decisions about the transfer of nuclear weapons are made behind closed doors, with furniture and flowers as the only witnesses, how can we learn what really happened? Who will tell us? Such questions about access tie the series to Simon’s previous work, most prominently An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, for which she photographed hidden places—the CIA’s art collection, transatlantic sub-marine cables reaching land—throughout the United States.

But Simon is not only asking about access; she’s also attempting to shift our focus away from the world leaders who make these decisions. In her series Birds of the West Indies, the artist scoured James Bond films and homed in on the women, weapons, vehicles, and birds in each movie; in doing so, she moved the locus of the franchise from its center to its margins. The shift in Paperwork and the Will of Capital is similar: by focusing on the flowers at political meetings, she prompts us to think about other details that might be overlooked—like, say, the millions of people affected by these negotiations. “Every revolutionary protest is also a project against people being the objects of history,” Berger once wrote. Simon’s flowers—which were, after all, once living things—want to speak out against their objecthood, and ours, to protest being overwritten by the tyranny of history.