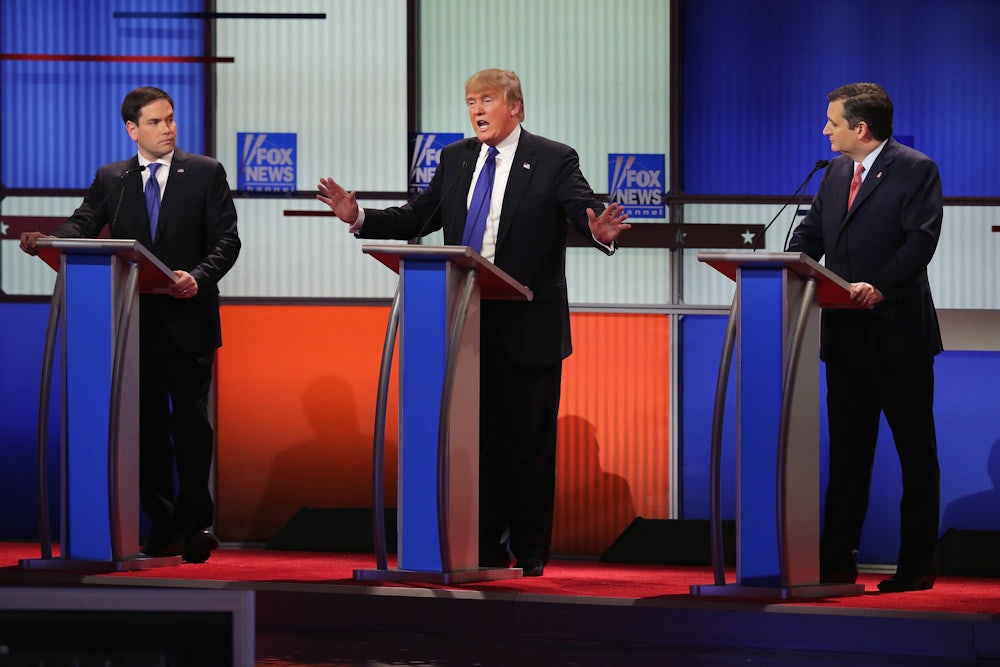

Thursday night’s Fox News debate was a two-hour anti-Trump smackdown with well-prepared moderators calling in assists from the billionaire’s opponents who, aside from accusing Trump of various iterations of fraud and dishonesty, said little. It’s no secret the Republican establishment is in full panic mode trying to shut down the Trump phenomenon, with 2012 GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney appearing this morning at the University of Utah to plead with voters to support literally anyone other than Trump. And, like Romney’s gambit, the tactic of the night was to frame Trump as a con artist, a fraudster, a liar; both a shady businessman and the kind of candidate who is nowhere near as tough, straight-talking, or sharp as he has presented himself thus far. So: Will it work?

The first thing to note is that the accusation that Trump is a con artist is made up of several different claims and types of claims, some of which Trump himself does not deny. Overall, the argument that Trump is conning political conservatives arises from three sources: his donations, his reversals, and his apparent flexibility. The accusations that Trump has mishandled his business ventures (as in the ongoing case of Trump University) are perhaps equally potent, as they deal with incidents of fraud as it is usually construed, and could seriously damage his image as a skilled businessman with a heart for the little guy.

More information about the Trump University suit and Trump’s resort employment procedures is doubtless forthcoming, but for now, here’s a look at the accusations of political chicanery that fellow Republicans hit Trump with tonight.

Early in the debate, Ted Cruz went over Trump’s history of donating to Democratic candidates responsible for many of the policies and programs Republican voters loathe, like Obamacare.

I feel like people have tried to bait Trump on this exact "you donated to Democrats" thing 1000 times and he always pounds that answer.

— daveweigel (@daveweigel) March 4, 2016

That was the best version of the "but for chrissake you donated to Democrats" attack, by far.

— daveweigel (@daveweigel) March 4, 2016

It wasn’t the first time Trump’s history of donations has been brought up, but it was perhaps the most effective. Still, Trump returned the same defense he’s always used: He’s a businessman who deals with everyone, which is also how things get done in Washington. “I have been supporting people for many years,” Trump said, “And these people have been politicians, and they’ve been on both sides, Democrats, Republicans, liberals, conservatives. I’ve supported everybody, because, until recently, I wasn’t a politician. ... And as a businessman, I owed that to my company, to my family, to my workers, to everybody to get along.”

For Trump, it’s a useful turn: He gets to remind GOP voters that it’s people like him who really control politics, meaning he has a better grasp on political action than his fellow candidates. It also has the added benefit of making the Democrats whom Republican voters detest seem beholden to Trump, while doubling as a self-compliment to his ability to conduct bipartisan business.

So far, ‘pulling back the curtain’ on how politics really work has been a major part of Trump’s appeal to frustrated groups (like Evangelicals) who feel their political priorities are seldom attended to by establishment Republicans, meaning Trump’s response could continue to boost him among some parts of his base. Further, Trump’s main support does not necessarily come from extremely conservative Republican partisans—the sort of voters who might be thoroughly off-put by too much elbow-rubbing with Democrats. Rather, Trump does well among moderate and liberal Republicans, again suggesting that his ability to make things happen with Democrats might be read as more of a feature than a bug, especially to any independents or Democrats he might still hope to pull into his fold.

What about Trump’s flip-flops? Fox’s moderators came prepared with video of Trump reversing his position on Syrian refugees, on President Bush’s alleged lies about Iraq, and whether or not intervening in Afghanistan was wrong, along with material from Trump’s past remarks (some off-the-record) and books—all in an effort to demonstrate that the Donald tends to waffle. So will these flip-flops slow the Trump train?

In short, it depends on the nature of the flip, the outcome of the flop, and whether his shifts are received as pandering or simply evolving.

Every politician flip-flops. The ones who claim otherwise are the ones you should be suspicious of.

— Christopher Ingraham (@_cingraham) March 4, 2016

In his response to Megyn Kelly’s probe of three recent reversals, Trump simply maintained that he has the right to educate himself, improve his positions, and change his mind. He emphasized that flexibility is an important quality of leadership. “Megyn, I have a very strong core,” he said, “I’ve never seen a successful person who wasn’t flexible, who didn’t have a certain degree of flexibility. ... You have to show a degree of flexibility.” He’s said as much (without detectable ill effect) within the last several days—offering, for example, to shift the size of his proposed Southern border wall by a few feet.

If Trump’s base accepts his explanation that leadership simply requires good bargaining skills, then the fact that he sometimes switches his positions might not impact his campaign. On the other hand, if Trump’s so-called flexibility on his core issue, immigration, is received as pandering to a gullible voter base without any real intent to follow through, his campaign might find it difficult to keep its footing.

Now Trump is trying to soften his stance on immigration. If that doesn't hurt him with Trump voters, nothing will. #GOPDebate

— James Downie (@jamescdownie) March 4, 2016

But what about flexibility itself? If Trump’s voters support him because he projects an authoritarian personality—that is, a persona that aggressively supports conformity and order, seeks to protect social norms, and views outsiders with suspicion—then too much flexibility might read as weakness, vulnerability, or fragility.

And it seems Trump knows that maintaining an authoritarian image is important to his continued success with his base. “I will say one thing, what Marco said is—I understand it. He is talking about a little give-and-take and a little negotiation. And you know what? That’s OK. That’s not the worst thing in the world,” Trump said. “There is nothing wrong with that. I happen to be much stronger on illegal immigration. Sheriff Joe Arpaio endorsed me. And if he endorses you, believe me, you are the strongest, from Arizona.” Invoking Arpaio resulted in wild applause, likely because Arpaio himself is known for particularly harsh implementations of his authority, with some accusing the Arizona sheriff of engaging in torture.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Trump also went out of his way to nod toward torture during Thursday’s debate. “Can you imagine—can you imagine these people, these animals over in the Middle East, that chop off heads, sitting around talking and seeing that we’re having a hard problem with waterboarding? We should go for waterboarding and we should go tougher than waterboarding. That’s my opinion,” Trump said, doubling down on past remarks he’s made promising to ramp up aggressive action against terrorists and their families. Trump also promised that even if his orders regarding torture were technically illegal, the military would still carry them out: “I’m a leader. I’ve always been a leader. I’ve never had any problem leading people. If I say do it, they’re going to do it.”

The Donald knows that disaster for his campaign is not looking too savvy or successful as a businessman—and not even as too moderate—but rather too weak, too susceptible to the will of others, too subject to the powers that be. As long as Trump can project an image of almost superhuman indifference to what other people want out of him, he can likely buck the con-man rap. But if the stink of softness sticks, he might be in trouble.