One July day in 1993, a senior curator at Israel’s national museum in Jerusalem approached a glass display case accompanied by a security guard. It was off-hours, and the museum was empty. On a little stand inside the vitrine was a tiny object bathed in light: a brownish, scarab-shaped stone about the size of a fingernail. If you bent down in front of it and squinted, you could make out an exquisite drawing of a twelve-stringed lyre, carved into the stone. Underneath the lyre, a two-line inscription in ancient Hebrew read: “Belonging to Maadana, daughter of the king.”

The artifact was identified as the signet of a princess from the biblical Kingdom of Judah, and it was dated to the seventh century B.C.E., when the Jewish First Temple is believed to have stood in Jerusalem. Her identity was a mystery; there is no mention of her in the Bible, and the seal does not name her royal father. Hundreds of ancient Hebrew seals have been unearthed in Israel since the nineteenth century. They are carved oval stones, sometimes as small as pebbles, which their owners would wear as amulets or stamp into small pieces of clay, leaving an imprint that would seal a document. To find an inscribed Hebrew seal or a seal impression, called a bulla, was to come face to face with an autograph of someone who lived in ancient Judah. Some of these seals and bullae even bore the names of people mentioned in the Bible—mostly marginal characters like Shevanyahu and Yaazanyahu, but also more prominent ones, like Berekhyahu, son of Neriyahu, the scribe of the prophet Jeremiah.

Unlike Mesopotamian cuneiform or Egyptian hieroglyphics, little written material from biblical times has survived the centuries, but ancient Hebrew seals and bullae are among the few exceptions. They are physical proof of the Israelite account, and their discovery and display feeds a fascination in Israel for vestiges of early Jewish life. “The Israel Museum plays an important part in our modern, emerging nation,” Martin Weyl, the museum’s former director, once wrote in an exhibition catalogue. “Walking through its galleries, the visitor understands our links with a long and distant past.”

The Maadana was a particularly rare find. Many Hebrew seals

are inscribed with the names of princes or royal male subjects, but very few

feature names of women; the Maadana is the only one attributed to female

royalty. The seal’s lyre motif was believed to be the most accurate depiction

of the famous lyre of the Bible, the instrument strummed by King David. Reuben

Hecht, a prosperous grain merchant and confidant to Israeli prime ministers,

who was an avid collector of biblical antiquities, bought the seal on the Jerusalem

antiquities market, and in 1980 he donated it to the Israel Museum.

Archaeology has always been a national obsession in Israel. In the country’s early years, amateur excavations took place at kibbutzim across the country, and children foraged for coins and seals in caves and fields. Digging for Jewish roots was seen as an act of nation building for a people trying to justify its existence to the world and to itself. “For the disquieted Israeli, the moral comforts of archaeology are considerable,” Amos Elon wrote in his 1971 book The Israelis: Founders and Sons. It provided a “reassurance of roots.” In the 1950s and ’60s, Israeli war hero Yigael Yadin excavated the country’s major archaeological sites and hosted a popular archaeology trivia show on Israeli TV. Hundreds of volunteers helped him dig Masada, the site of the fabled Jewish revolt against the Roman army, and the remains of those who were believed to be Masada’s heroic Jewish defenders were given a military reburial. The excavation inspired an entire generation of young Israelis. “In archaeology they find their religion,” Yadin said in a 1968 interview. “They learn that their forefathers were in this country 3,000 years ago. This is a value. By this they fought and by this they live.”

In the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights. Almost immediately, it launched an “emergency survey” of hundreds of sites in the region. Most Israeli archaeologists took their spades to Sinai, but when it became a theater of war in 1973, they shifted their focus to the West Bank, the center of ancient Israelite life and home to the biblical cities of Bethlehem, Hebron, and Jericho. Major digs were conducted at Tel Shilo, where the Bible says the Israelite Tabernacle once stood, and at Mount Ebal, where the Israelite tribes gathered for curses. While the government helped religious nationalist Jews settle the land they believed God promised them in the Bible, it also earmarked funding for academic digs in the territory. In the 1980s, about a third of Israeli archaeology Ph.D. candidates focused their research on the West Bank.

The Israeli occupation was also a boon for collectors. A deluge of coins, figurines, pottery, oil lamps, and other ancient flotsam flooded the antiquities market, fueled largely by enterprising Palestinian treasure hunters whose villages were built atop the ruins of ancient towns. A coterie of wealthy Israelis—including military chief Moshe Dayan and Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek—built private collections, paying antiquities dealers top dollar for the most impressive finds. Hecht amassed Israel’s largest collection of Hebrew seals and bullae from the First Temple era. He donated the best of his collection to the Israel Museum, including the Maadana.

The seal remained on display for 13 years, until that day in 1993, when the security guard unlocked the glass case and the curator pinched the seal between her gloved fingers and dropped it into a small container the size of a ring box. She also removed the enlarged diagram of the seal propped up in the display case. The guard accompanied the curator down to the museum’s basement storage facility, where she pulled open the glass doors of a tall wooden cabinet and placed the Maadana inside.

It was done quietly. The curator made no note of it on the seal’s registry card, the little index card that logged its display history. No announcement was made. It never went back on exhibit at the museum. It was removed amid allegations that the Seal of Maadana was a fake.

“An exceptionally interesting and beautiful Hebrew seal has recently appeared,” wrote Nahman Avigad, then Israel’s preeminent expert on ancient Hebrew inscriptions, in a January 1979 article for Israel Exploration Journal. The opening line came with a footnote: “The seal is in the collection of Dr. R. Hecht of Haifa, to whom I am much indebted for permission to publish it. It is said to have been found in Jerusalem, but its exact provenance is uncertain, as is true of all seals which were not found in controlled excavations.”

Hecht died in 1993, leaving behind no record of who sold it to him. Harry Zesler, who was in charge of the finances for Hecht’s antiquities purchases, told me Hecht did not involve him in the purchase of the Seal of Maadana—which is curious, considering that it was Hecht’s most expensive seal acquisition. Hecht told Zesler he paid 500,000 Israeli liras for it, the equivalent of about $96,000 today. “In his eyes, this was the most important seal he ever purchased,” Zesler said. He added that there was no documentation of the purchase, but Israeli antiquities dealers and collectors say one of the people Hecht was known to buy similar antiquities from was an Israel Museum conservator turned antiquities dealer named Raffi Brown.

“Except for its conventional shape, every aspect of this seal is unfamiliar: its decoration, the name of its female owner, and her title,” Avigad wrote in his journal article. The name, pronounced Ma-Ah-Da-NA, a derivative of the Hebrew word for “delight,” does not appear in the Bible. No other seal, in Hebrew or any other Semitic language in the region, had been found with the name of a princess. “Whether the Maadana of our seal held a special position which necessitated the use of a seal remains unknown,” Avigad wrote. “However, the status of a royal princess was distinguished enough for her to be the owner of a private seal.”

Avigad found basic similarities between the lyre on the seal and lyres depicted in non-Jewish art of the Near East, as well as on Jewish coins of the second century C.E. and a sixth century C.E. Gaza synagogue mosaic of King David. But he also found differences. He listed them: “The elegantly curved arms, and especially the unusual shape of the sound box, partly rounded and partly carinated and exceptionally decorated with a rosette. None of the known parallels has a decorated sound box. Does this rosette have any symbolic meaning? We do not know.”

He dated the seal’s inscription by examining the style of the lettering. Based on the seal’s emblem, he concluded that Princess Maadana was “an ardent lyre player.” The detailed sketch of the lyre, he said, provided the closest glimpse of what the Bible calls the kinnor—the lyre that was played in the temple, and the lyre of King David. “Our lyre may be regarded as the first true Hebrew rendering of this musical instrument,” he wrote.

Hecht donated the seal to Israel’s national museum a year after the article’s publication. Teddy Kollek, the mayor of Jerusalem, unveiled the seal at a ceremony to inaugurate a new permanent exhibit Hecht funded in his parents’ memory, the Jacob and Ella Hecht Pavilion of Hebrew Script and Inscriptions. It was dedicated to objects that had survived from the First Temple period, many of which Hecht himself had donated, including the bulla of prophet Jeremiah’s scribe. The inscriptions were celebrated as rare physical evidence from a golden age of ancient Israelite culture. In 1982, Biblical Archaeology Review, an American magazine with a large evangelical Christian readership, devoted a two-page spread to the Maadana seal. “We are grateful to her for showing us so beautifully what an ancient lyre looked like,” read the article. “No doubt she loved music and played the lyre herself, a message now wordlessly communicated across the millennia.”

Two years later, in 1984, Israel was experiencing hyperinflation caused by years of government deficit spending. The Bank of Israel, seeking to mitigate the economic difficulties, decided to chop off zeros from the value of the shekel and issue a new series of coins, the New Israeli Shekel. A committee of experts in fields including archaeology, numismatics, art, and biblical studies was convened to select the design for the new money. In the fall of that year, the committee selected Maadana’s lyre to adorn the largest of the new coin series, the golden-hued half shekel.

Israel has always modeled its specie on ancient Jewish coins and artifacts. The first coin it minted in 1949, a 25 mil piece, included an image of a cluster of grapes that adorned a coin struck during a second-century C.E. Jewish revolt against the Romans led by famed rebel Simon Bar Kochba. The ten-agorot coin currently in circulation depicts the seven-branched menorah found on a coin struck some 2,000 years ago during the reign of Mattathias Antigonus II, the last king of the Jewish Hasmonean dynasty, which ruled the Holy Land for close to a century. The two-shekel coin used today bears a pomegranate flanked by cornucopias, an image that decorated bronze coins during the reign of John Hyrcanus I, who expanded the borders of the Hasmonean Dynasty and converted local populations to Judaism. The word “shekel” itself comes from the Bible; it was the unit of weight used in ancient Israel for financial transactions.

As the Bank of Israel was preparing to unveil its new coin designs, a musicologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem named Bathja Bayer had a conversation with Rachel Barkay, an expert in ancient coins at the Bank who was also writing the official literature about the artifacts chosen to adorn the new money. Bayer was a specialist in the archaeology of music and had devoted much of her studies to biblical lyres. She said that she had information about the Maadana. It turned out she had some startling news: The princess, the lyre, the entire seal, Bayer said, was a forgery.

The Maadana lyre could never have existed in any ancient culture, she argued. Its asymmetrical sound box was unlike any other known ancient lyres, and with the crossbar resting on the top of outcurving arms, the instrument would collapse the first time it was tuned. The twelve strings tightly squeezed together in the tiny lyre corresponded to a written description of the twelve-stringed lyre of the temple by the writer Josephus Flavius. But Josephus’s account was historically doubtful; he lived more than 700 years after the period ascribed to the Maadana, leading Bayer to suggest the seal may have been designed to fit Josephus’s description. Furthermore, Bayer argued, it was unlikely a woman of royalty in seventh-century B.C.E. Jerusalem would wish to publicly associate with a lyre. In those days, she said, a female musician would have been considered a prostitute.

Barkay was surprised. “I thought to myself that Bathja’s claims held weight and were convincing,” she said. And yet Avigad, Israel’s premier seals expert, had given the Maadana his imprimatur. On August 25, 1985, Bayer wrote a memorandum on the lyre, which she sent to the director of the Bank’s currency department. “Pursuant to our conversations, I am sending the attached summary of the analysis regarding the authenticity of the seal,” she wrote. (After Bayer died of cancer in 1995, her papers were moved to the National Library of Israel; I was unable to find the summary in her archive.)

Bayer then took a turn for the clandestine. “It is best to limit the dissemination of what is written here to the necessary minimum,” she wrote, “in order to answer the immediate need.” That need, she wrote, was to stop the minting of a coin bearing the Maadana’s lyre with the Israeli government’s stamp of approval. But it was too late. The design had been chosen, a cast prepared, and the coin was already being minted and stockpiled. A week later, on September 4, 1985, hundreds of thousands of Maadana lyres found their way into coin purses and cash registers throughout the country. They remain legal tender in Israel to this day.

Amid Bayer’s papers at the National Library, wedged in a thick folio marked “unpublished articles,” is “A Case of Forgery and Its Ramifications,” a handwritten transcript of a lecture Bayer delivered about the Maadana at a 1990 archaeomusicology conference in France. By that time, the coin had been in circulation for five years.

“As you know,” Bayer wrote in her lecture notes, “the accumulation of the material relics of the ancient Near East, in public and private collections, already has a long history. So has the dark side of all this; for where there is a demand there will be a supply. The illegal excavators are always busy, and so are the forgers.”

As in her memorandum to the Bank of Israel, Bayer laid out her critique of the lyre. She also presented her theory about its origins. “It took me a few years of staring at the Maadana lyre to discover its conceptual prototype,” she said. It was the dainty pseudo-lyre, she concluded—the stylized instrument that the female muse would strum in nineteenth-century neo-classical paintings. “The lady with the lyre became a veritable fashion and fad then,” she noted. The lyre icon resonated with Israelis: It recalled King David’s harp. The biblical lyre is not at all a harp—that was a mistranslation—but no matter; Israel hosts an international harp contest inspired by the story of King David, and David’s harps are sold as souvenirs in Jerusalem.

Bayer said she phoned Avigad after reading his article to ask for a meeting to discuss her concerns. He declined. “I have determined that the seal is authentic; a musicologist’s opinion cannot change this; and there is no need for a meeting,” she quoted him as saying. “The gentleman has one well-known failing,” Bayer told the room of academics in France. “He never admits that he could have been mistaken.”

“The story of the Maadana lyre is not ended yet; but I have to end now,” Bayer said as she concluded her talk. “Thank you; and please return all the handouts, because the time has not yet come for the Maadana affair to be made too public.” Afterward, an Israeli musicologist who had attended the talk remarked to a colleague that it was inappropriate for Bayer to have presented their country in such a bad light at an international conference. That colleague believes Bayer overheard the comment. Whether she in fact did is not known. Either way, Bayer did not submit her conference paper for publication. She may have been hesitant to create controversy over an icon Israelis had come to accept as a cherished symbol of their past.

Avigad died in 1992, and a year later Bayer attempted to go public with her findings. She proposed a paper on the topic to the Israel Exploration Journal, which had earlier published Avigad’s paper. Titled “Inventing a Princess and Her Lyre,” the six-page proposal outlined her academic analysis, her last-minute attempt to stop the Bank of Israel from minting the Maadana-inspired coin, even her theory that a modern forger had consulted her entry on ancient lyres in the Encyclopedia Biblica when crafting his seal.

The journal rejected her proposal. But word had already gotten out. Two months earlier, in July of that year, Yerushalayim, a Jerusalem newspaper, ran a short blurb declaring the Maadana a fake. “Professor Avigad wrote a story about the seal that could belong to the Brothers Grimm, or to One Thousand and One Nights,” Aharon Kempinski, then head of the Association of Archaeologists in Israel, was quoted in the article as saying. He endorsed Bayer’s theory. Israeli musicologist Joachim Braun, who had initially been critical of Bayer’s talk, also wrote about the Maadana’s problematic lyre. The list of scholars questioning the seal was continuing to grow. Shortly after the newspaper piece was published, the Seal of Maadana was removed from display at the Israel Museum.

Before Nahman Avigad died, he had been working on a comprehensive survey of every known ancient Western Semitic seal and bulla. It was a colossal task, and his family and other academics asked Israeli epigraphists Joseph Naveh and Benjamin Sass to complete his work. They sifted through a hoard of photographs and clay seal impressions at Avigad’s home and office, and in 1997 published the Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, today considered the scholarly standard for the understanding of ancient Hebrew seals.

Buried in the preface is a note of caution. “Beginning in 1968, dealers and collectors brought Professor Avigad a series of seals and bullae bearing somewhat peculiar iconography and letter forms, presumably produced by a limited number of engravers,” Naveh wrote. “Since no such seals were previously known and none of them was of clear provenance, there were rumors among scholars concerning their authenticity.” He listed 49 examples, including the Seal of Maadana. A later research article Naveh co-authored noted:

One should bear in mind that many West Semitic seals and bullae, mostly Hebrew ones, bought on the antiquities market since ca. 1970, may have been produced by a skilled hand, with somewhat peculiar iconography and letter forms not represented in the epigraphical corpus known at the time of their publication. Although it is impossible to prove definitively that these seals are forgeries, there is room for suspicion that modern forger(s) might have had excellent knowledge of Biblical Hebrew and Old Hebrew epigraphy, and possessed the technical ability to produce seals … of very high quality.”

The corresponding footnote mentions one item: the Seal of Maadana.

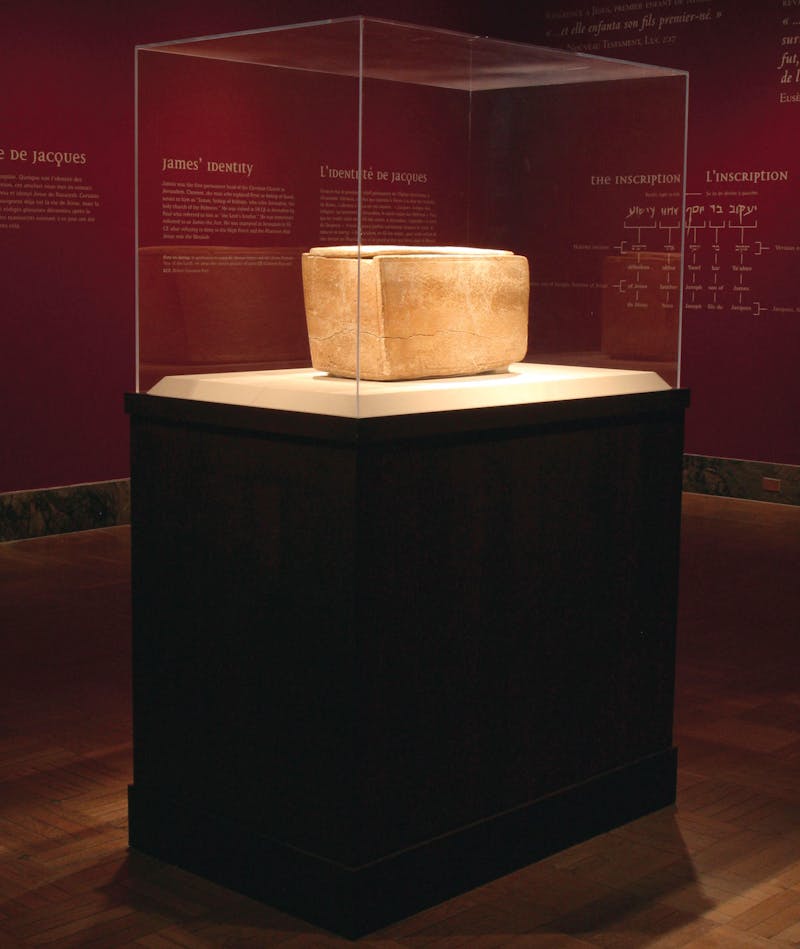

In the fall of 2002, Biblical Archaeology Review ran a cover story entitled WORLD EXCLUSIVE! EVIDENCE OF JESUS WRITTEN IN STONE. It announced the discovery of an ossuary, or burial box, inscribed with the name of Jesus’ brother James—a physical connection to the historical life of Jesus. Around the same time, Israeli authorities had been looking into reports that a large sandstone tablet had surfaced with an ancient Hebrew inscription outlining repairs made to the First Temple by King Jehoash, as described in 2 Kings, Chapter 12: “And Jehoash said to the priests … they shall repair the breaches of the house, wheresoever any breach shall be found.” If real, this would be the first physical evidence of the existence of the First Temple.

Both archaeological discoveries caused a sensation. But by that point, experts had grown skeptical of sensational discoveries. The Israel Antiquities Authority, or IAA, a government agency, carried out a months-long investigation, questioning suspects and conducting searches for the Jehoash Tablet. A tip led investigators to Oded Golan, a Tel Aviv antiquities collector who was in possession of the James Ossuary. He knew the whereabouts of the tablet, too, and after it was seized, the IAA appointed a panel of 14 experts to determine whether it was authentic. The panel also conducted an examination of the James Ossuary.

In June 2003, the IAA announced to the press that it had determined that both items were modern fakes. The ossuary was ancient, but the inscription was modern, and the etching was filled with dirt and gold flecks to make it look ancient, officials said. The tablet contained a linguistic anachronism— a modern Israeli phrase—the IAA said. Shuka Dorfman, then the IAA head, said Golan had tried to sell the tablet for $2 million. “We want to find out who is behind this,” Dorfman told The New York Times.

In 2004, Israel’s state prosecution charged Golan and four other men with masterminding a forgery ring responsible for faking the James Ossuary, the Jehoash Tablet, and a trove of other Bible-era antiquities. “During the last 20 years many archaeological items were sold, or an attempt was made to sell them, in Israel and in the world, that were not actually antiquities,” the indictment read. “These items, many of them of great scientific, religious, sentimental, political, and monetary value, were created specifically with intent to defraud.” Dorfman told the press that the forgers had been “trying to change history,” exploiting those who sought physical proof of the Bible. Such proof would have far-reaching religious implications for Christianity and Judaism, as well as political implications for Israel’s historical claims to the Holy Land.

What resulted was the highest-profile archaeological forgery trial of the past century. Virtually every major figure in Israel’s tight-knit biblical archaeology community was summoned to the stand, and a far-ranging group of suspected antiquities fakes were examined in court. For the first time since the late 1800s, when Jerusalem antiquities dealer Moses Wilhelm Shapira was found to have forged thousands of biblical antiquities, Israeli officials believed they had zeroed in on antiquities forgers and their methods.

There was one dubious artifact that did not receive its day in court: the Seal of Maadana. It had surfaced around 1978, placing it outside Israel’s statute of limitations, which lasts ten years for serious fraud offenses. Therefore, it was not officially part of the forgery trial. But during the trial, patterns began to emerge that linked the Maadana with other suspect antiquities, offering possible clues about its origins.

One witness called to the stand, a Glasgow-born antiquities dealer in Jerusalem named Lenny Wolfe, presented a sweeping theory to the court connecting the dots between an assortment of suspected forgeries. In the course of his work collecting and dealing in dozens of ancient Hebrew seals, Wolfe testified, he came to notice a small epigraphic oddity in many of the seals that epigrapher Joseph Naveh had labeled as suspect: a droopy leg at the base of the Hebrew letter bet. The letter was never written like that in ancient times, Wolfe argued. In the manner of a forensic handwriting analyst, Wolfe believed the epigraphic quirk revealed that the inscriptions were all forged by the same hand, which he dubbed the Lame Bet Workshop.

As the trial proceeded, he published a paper in the German academic journal KUSATU analyzing a number of seals, including the Maadana. “The leg of the ‘bet’ does not have the sharpness expected of a genuine letter. Furthermore, the head of the ‘bet’ is too rounded and somewhat disproportionate,” he said of the Maadana. He found a similar lame bet on an inscribed ivory pomegranate attributed to the first temple, a prized possession of the Israel Museum that scholars had argued was a forgery. André Lemaire, a Sorbonne professor who was the first to publish on the existence of the ivory pomegranate and who considered its inscription authentic, attacked Wolfe’s paper, arguing that ancient Hebrew inscriptions contained many variations of the letter bet. “What does this paper reveal? Clearly lame knowledge and lame methodology,” Lemaire wrote. (Lemaire told me he is undecided about the authenticity of the Maadana.)

Wolfe believed there was one other curious similarity between the Maadana and other inscriptions of dubious authenticity that had surfaced on the Jerusalem antiquities market between the late 1960s and early 1990s. They had passed through the hands of one of the men on trial: Raffi Brown, the Israel Museum’s former chief conservator.

During Raffi Brown’s decade and a half at Israel’s national museum, he was known as a brilliant conservator, artfully restoring ancient pottery and seamlessly filling in missing parts of broken artifacts to prepare them for exhibition. One of his greatest talents was creating replicas. “I remember once we gave him a dagger, a bronze dagger,” said Joe Zias, a former curator at the Israel Antiquities Authority. It was slated for display abroad, but Israel didn’t want to ship the original, so Brown made a reproduction—a common practice with artifacts of high value. “I looked at them, I couldn’t tell which was the authentic one, which was the copy. He was that good,” Zias said. “He was probably one of the world’s best.”

Brown also cultivated an expertise in authentication, appraising items that surfaced on the market and ensuring they were legitimate before the museum would acquire them. Replication and authentication require similar skills: If you know how to duplicate, you can recognize a dupe. Like patients lining up for a renowned physician, top antiquities collectors would seek Brown’s opinion. When a collector was considering purchasing an item and donating it to the Israel Museum, it was often Brown’s word that would clinch the deal, one former collector told me. His word was worth a lot of money, and his expertise was known to come at a price, he said. “Someone buys it for half a million, and Raffi, in the middle, gives it the OK. So, what, he won’t get a cent for that?” the former collector said.

During the trial, prosecutors accused Brown of selling a fake bulla stamped with the inscription “Belonging to Berekhyahu, son of Neriyahu, the scribe,” who is mentioned in the bible as the prophet Jeremiah’s scribe. There are a couple of links between this suspect bulla and the Maadana. Hecht, the man who bought the Maadana, also bought a bulla with a Berekhyahu inscription in the 1970s and gave it to the Israel Museum. Who sold it to Hecht is unknown. But 20 years later, Brown sold an identical bulla for $100,000 to Israeli multimillionaire antiquities collector Shlomo Moussaieff through an intermediary named Robert Deutsch. Hecht’s bulla also fell outside the statue of limitations for the trial, but prosecutors argued the sale of Moussaieff’s fell within it, and accused Brown and Deutsch of forging it. Yuval Goren, an Israeli archaeologist who examined the bulla, testified that a layer of patina—grime that naturally develops on objects over time—appeared to be glued onto the bulla, raising suspicions that it was fraudulently added to the object to make it appear ancient. Brown said he had coated the bulla with an adhesive only as a method of conservation. Meanwhile, Deutsch argued that the sale of the bulla took place in 1991, which would place the object outside the statute of limitations by two years. The judge eventually ruled that there was not enough evidence to rule it a forgery. (In 2014, Goren and Israel Museum curator Eran Arie compared both bullae to more than 100 bullae found in scientific excavations, and found the Berekhyahu bullae to be modern forgeries.)

Experts have questioned other antiquities that Brown is connected to. There’s the ivory pomegranate inscribed with the ancient Hebrew phrase “Belonging to the temple of Yahweh, holy to the priests.” An anonymous donor purchased it for the Israel Museum from an anonymous collector via Brown for $550,000. The Israel Museum formed a committee of experts to examine the artifact’s authenticity. The panel, which included the Israeli Police forensics unit, concluded the ivory pomegranate was ancient, but the Hebrew inscription was a recent addition. Once again, a patina-like substance of organic material and modern adhesive had been glued onto the Hebrew inscription, the experts concluded. Once again, Brown said he only touched up scratches and added glue to strengthen the object.

Another suspect object Brown is connected to depicts a sailing ship and bears the ancient Hebrew inscription “Belonging to Oniyahu, son of Merab.” In 1985, the same year that the Bank of Israel featured Maadana’s lyre on the half shekel coin, it featured Oniyahu’s boat on a commemorative silver shekel. Israeli Bible scholar Shmuel Ahituv, who last year won Israel’s highest state honor, the Israel Prize, considers it a forgery. Oniyahu translates to “God is my strength,” but the icon of a boat, oniya in Hebrew, is a play on words he says no one in ancient Judah would have used. In 2013, Michael Steinhardt, an American hedge-fund manager and Judaica collector, sold the seal at Christie’s in Rockefeller Plaza in New York for $93,750. He had purchased it in a 1992 auction at Numismatic Fine Arts, a Beverly Hills gallery on Rodeo Drive. Brown put it up for auction.

In the trial, however, Brown was only accused of involvement with two alleged forgeries: the Berekhyahu bulla, with Robert Deutsch, and an inscription on a piece of pottery, with antiquities dealer Shlomo Cohen. Prosecutors eventually dropped the charges on the pottery inscription, and since Brown was only left with one remaining charge, prosecutors agreed to continue his proceedings in a different trial. Then prosecutors decided to drop the remaining charge, too, citing in part a lack of public interest in spending resources on another separate antiquities trial. Brown was cleared of the forgery charges. So were the rest of the suspects.

The trial is over, but in Israel’s antiquities community, many believe that only a man with Brown’s expertise and artistic skills could have forged seals, bullae, and other objects of suspect provenance. When I reached Brown by telephone at his Mediterranean seaside home north of Tel Aviv, he said he had lost sight in one eye and was no longer active in the antiquities business. I asked him about Wolfe’s allegations that he was connected to the group of suspect antiquities, including the Maadana. “I’m out of it for quite a few years,” he said. “I really don’t want to mention it, talk about it. Let Lenny Wolfe do what he wants. With all respects, I’m out.” I asked him about the authenticity of the Seal of Maadana. “I am not thinking about it,” he said. “I don’t want to say anything bad or anything good. There are enough experts besides me. Let them decide what they want.”

Robert Deutsch, one of Brown’s co-defendants in the forgery trial, has no such uncertainties about the Maadana. “Of course it’s forged,” he said when I visited him in late 2013, adding that he doesn’t know who forged it. Deutsch operates an antiquities shop in a quaint alleyway in Jaffa’s walled old city, on the Mediterranean shore. LICENSED TO SELL ANCIENT HISTORY reads the sign outside his shop. Deutsch had published some 1,200 seals and bullae, many of them in Shlomo Moussaieff’s collection, and used to teach courses in paleography at the University of Haifa, before he was dismissed as a result of the trial. He was seated behind a desk in his office, staring at me through eyeglasses taped together on one side. He reached for the encyclopedia-sized Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals and flipped to the Seal of Maadana entry.

“In this seal, they made all the mistakes possible,” Deutsch said, noting anachronisms in the shapes and stance of the ancient Hebrew letters in the inscription. He compared it to an English speaker copying Chinese characters. “There’s no one who thinks the Maadana is good,” Deutsch said. (“Good” is archaeology-speak for “authentic.”) I asked if it bothered him that the coin with the Maadana’s lyre was still in circulation, despite the scholarly consensus.

“You have a shekel in your pocket?” Deutsch told me. “Take it out, and tell me what you see.” I pulled a small silver coin from my wallet. On the front were a three-leafed flower and three letters in ancient Hebrew script.

I held it between my thumb and forefinger and stared. “It’s the fleur-de-lis, no?” I asked. “And I assume that says shekel in ancient Hebrew?”

“You don’t know nothing about it,” Deutsch said. He was right. It is not a fleur-de-lis; that is a Christian icon. It is a lily, from a Judean coin of the fourth century B.C.E. The three letters spell out the word Yahud, or Judah, which is written on the ancient coin. He had proven his point about the Maadana coin. Not many people know their history, or care to know it.

This spring, Eran Arie, curator for Israelite-era archaeology at the Israel Museum, took me to the museum’s basement storage room to see the Seal of Maadana. We put on blue latex gloves and Arie opened a white cardboard ring box to hand me the small brown stone. To finally see it up close was underwhelming. Even under a bright light and large magnifying glass, the engraving was hard to make out.

Though the Israel Museum has engaged expert committees to examine the authenticity of the ivory pomegranate and the bulla of Jeremiah’s scribe, it has yet to properly examine the Seal of Maadana. American epigraphist Christopher Rollston, who visited the Israel Museum in 2013 to examine the seal under a microscope for a forthcoming paper, concluded the seal is a forgery, arguing the tool used to engrave the seal was of a different size than tools that engraved seals of the same period found in proper excavations. Ancient seals resist definitive scientific testing, however. Radiocarbon testing can date the organic material on bits of string stuck to a bulla, and thermoluminescence testing can determine when one came in contact with fire. But with a seal, there are no altered chemical properties to check. It’s just cut rock.

It has been difficult for Israeli officialdom to embrace the scholarly consensus about the Seal of Maadana. Calling relics like this into question could be seen as unpatriotic, casting doubt on the roots of Jews in the land, undermining the very existence of the Jewish state. “Those who connect archaeological sciences to identity, to the issue of national identity, are setting themselves up for a fall,” Raphael Greenberg, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University who studies the politics of Israeli archaeology, told me recently. “Archaeology can change. I mean, interpretations can change. And things assumed to be one thing turn out to be another.”

In the 30 years since the Bank of Israel turned the Maadana into one of the country’s most ubiquitous icons, it has had ample opportunity to publicly address questions regarding the seal’s authenticity and determine whether it should continue to adorn Israeli currency. Instead, the Bank has passed the buck.

Ahituv, the Bible scholar, contacted the Bank of Israel in recent years and asked why it had not stopped circulating the half shekel coin. He said he received no answer. Dov Genichovsky, a veteran Israeli journalist who sat on the Bank’s currency design committee from the time it picked Maadana’s lyre for the half shekel until today, said Bank officials never told the committee there were doubts about the seal. Not that it would have mattered to him. “Archaeologists will argue for one hundred years,” he said on the phone. “Why should the respected gentlemen of the committee enter the debaters’ shoes and decide?”

Rachel Barkay, the numismatist who brought Batya Bayer’s doubts to the attention of the currency department, and who later became the Bank of Israel’s chief numismatist, never mentioned the seal’s suspect authenticity in any Bank literature and would decline comment whenever the forgery rumor came up during her guided tours at the Bank. When the Maadana motif was chosen, she said, no one on the design committee was aware of any doubts about the artifact. Today, Barkay does say she tends to believe the seal might be a forgery. But, she added, it was not the bank’s responsibility to rule on its authenticity.

I met with Moti Fein, the head of Bank of Israel’s currency department, in 2014. (Fein has since left his post.) A spokesperson for the Bank was in the room with us. The conversation took place on the condition that I send him the quotes I wanted to print for his approval. When I did this the spokesman rejected the quotes, and provided this statement:

There is no proof that the “Maadana, Daughter of the King” seal is not authentic. And even if it isn’t, it bears no importance in terms of the coin itself, many years after it was issued. The public can rest assured that the coin in its hands is legal tender in every way, and the Bank of Israel has no intention of changing or replacing the coin, except during a complete replacement of the coin series if and when this takes place in the coming years.

Last June, a curator from the Hecht Museum in Haifa, which displays many ancient seals, coins, and relics that the late Reuben Hecht had purchased, came to the Israel Museum to collect the Seal of Maadana. Representatives from the Hecht were upset it had been taken off display and maintained that there was no proof that it was a forgery. They wanted it to be displayed in Israel again. Negotiations had dragged on for years. The Israel Museum finally agreed to give the Maadana to the Hecht on long-term loan, on condition that the display label include a disclaimer stating that its authenticity was the subject of debate. The seal is now on display at the Hecht.

So, the Israel Museum no longer provides a home for this contentious artifact. But its gift shop continues to sell replicas on sterling silver bracelets, pendants, bookmarks, and rings, accompanied by a pamphlet calling it an ancient Hebrew seal of the seventh century B.C.E. On a recent visit, a saleswoman told me it is a popular bat mitzvah gift.