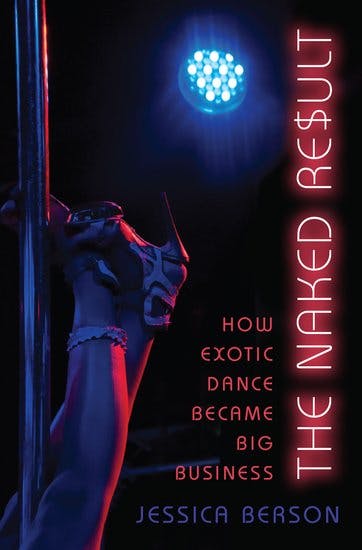

Just as college students have a window for reading The Brothers Karamazov, and middle-aged men have a few years in which to buy a little red Corvette, young women have a finite period in which they can figure out what is “dancing sexy,” a phrase Jessica Berson uses early on in The Naked Result: How Exotic Dancing Became Big Business, her new book about the exotic dancing industry.

The desire to seek out sexy dancing is largely a twentieth-century male pastime. Slumming it at the burlesque theatre, the locus classicus until the 1960s of striptease, male writers and journalists saw “dancing sexy” as a metaphor for the act of sex: Henry Miller described Cleo’s lusty grind, Edmund Wilson called the shaking and stripping he saw at Minsky’s Burlesque “the orgasm dance.” In 1957, Roland Barthes wrote that “the faintly rhythmical undulation exorcises the fear of immobility.” It was only with the sexual revolution that women began to write about what dancing sexy meant for them. Today the phrase can refer to the proximity of the stripper to the customer, what she’s wearing, the style of movement, her confidence, and what Berson calls here “authenticity,” one of those distinctions that’s easier to proclaim than define.

I took a turn at figuring out “dancing sexy” in my first book, Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show, a subject I became interested in when a graduate school friend began stripping. But it wasn’t until years later, at the book’s launch party, that I had a moment of clarity. I had hired a stripper for the celebration at the Slipper Room on the Lower East Side, not far from the former site of Minsky’s, where 80 years earlier women took off their clothes on stage for the first time in America. As I looked around, I saw New Yorkers—mostly editors and publishing executives—more preoccupied by the question of who would be at the next networking event than by the redhead on stage. Then the music started, and the stripper commenced taking off her clothes. The room fell silent. No one could take their eyes off her. Although everyone was able to pretend that striptease was passé, “dancing sexy” illuminated the illusory and anarchic power of the striptease. It was like a lullaby, but for fucking.

Reading The Naked Result, I was curious to learn what Berson thought had changed about this world in the past eleven years. Between the early 1990s, when I started working on Striptease, and 2004, when it came out, third-wave feminists transformed the way stripping was perceived. While second-wave radical feminists had largely regarded striptease as a gateway to porn, sexual violence, exploitation, and objectification, writers such as the late Ellen Willis and Susie Bright, and scholars including Gayle Rubin, argued that sex work could be empowering for women. Certain regulations on strippers and strip clubs had eased, and while striptease has been partially protected in some states under the First Amendment since the 1960s, the expansion of gentlemen’s clubs in the ‘90s saw a flurry of court cases debating protections for nude dancers. At the same time, strippers have demanded, with some success, to be counted as employees. In 2013, for example, strippers won a class action suit against Rick’s Cabaret, a publicly traded company, and they were no longer cast as independent contractors or required to pay clubs a fee to perform.

Berson is a married ex-stripper, independent dance scholar, and expert in Laban Movement Analysis who worked for a while at Backstage Bill’s—a now-closed New Haven “juice bar,” the name for clubs that don’t serve alcohol in order to proffer full nudity—and Diamonds, one of a regional chain of so-called “gown clubs” in Hartford, which has one section for nude dancing and one topless section. Berson stopped stripping to have children and pursue her career as a scholar. The two Connecticut clubs she writes about are meant to show how corporate clubs are overtaking the indies. At Bill’s, glitter-clad women bumped, ground, and shimmied, as well as performed themed dancing with cowboy hats or schoolgirl skirts or outlandish wigs. Women with a wide variety of body types and races could work there. Diamonds was corporate, like a Barnes and Noble. The dancers there looked like The Girl Next Door: white, slim, young, pretty.

Berson’s career trajectory reflects the explosion of serious, scholarly interest in the striptease the third wave brought about. Throughout The Naked Result, she returns to the radical promise of striptease, quoting scholars and critics such as Terry Eagleton: “There is something in the body which can revolt against power which inscribes it.” She also nods to how by the 2000s, striptease had been recast as aspirational. Stripper memoirs became a genre, like travel writing or romance, and they were reviewed by literary critics. (Berson doesn’t describe how their authors graduated from stripping to become accomplished journalists and screenwriters, like Elisabeth Eaves, Diablo Cody, or Lily Burana, all of whom work hard in their books to address how stripping made them confront the gender inequities second wave feminism had failed to solve.) At the same time, stripper-chic became a profitable market, as suburban moms began attending pole-dancing classes. Sisqó’s “Thong Song” came on the radio and suddenly civilians were wearing the kind of underwear formerly worn on stage.

Yet, as Berson points out, despite feminism’s commitment to sex positivity, the theoretical conversation about striptease has not advanced much since the ‘90s. The positions of second and third wave feminists have become entrenched, polarizing opinions about sex work. “Many feminist scholars,” Berson writes, “have demanded that I take one side or the other—that I confirm their understanding of stripping as empowering or degrading.” To her credit, Berson tries to avoid the dichotomy. “Just because I felt sensual pleasure and a sense of embodied agency while dancing doesn’t mean that agency was real.” And later: “Some dancers had graduate degrees; some had never attended high school; many lived from night to night, staying in motels because they couldn’t save enough money for a deposit and first month’s rent.”

What is most interesting about The Naked Result is Berson’s observation that even as more young women become convinced stripping will set them free, strip clubs are becoming more proscribed. Once upon a time, women performed striptease that was about intimacy and self-expression with “authenticity,” as Berson puts it. Strippers of all races and body types worked together. They offered many different types of fantasies. Their acts were not necessarily XXX. In the 1990s, a new brand of corporate clubs began to Disney-ify striptease. “The corporate packaging of striptease, as American as Frappuccino,” she writes, “is rapidly repackaging the most mysterious human emotions into easily branded experiences no more personal or powerful than those to be found in any coffee mega-chain.”

Berson tells of how two clubs in London—Spearmint Rhino and Stringfellow’s—adopted American-style lap dancing, as “a case study” in the branding of striptease. In 1996, British businessman Peter Stringfellow opened a gentleman’s club in Westminster, a fashionable part of London, which he thought would bring in more money by lending an aura of class. Arcane licensing laws in the UK forced his dancers, as Berson puts it, to wear “knickers” and do their lap dances “a meter” away from customers, but Stringfellow worked hard to create an atmosphere of decadent respectability, installing vast chandeliers and velvet thrones, and granting good-natured interviews on talk shows. By 1999, however, his dominance was interrupted, when American club owner John Gray decided to export his ten-year-old franchise, Spearmint Rhino, to the UK, launching what Berson calls a “lap dance war,” with much spying on the competition and attempts to steal their dancers.

While Stringfellow’s role model was Hugh Hefner, Gray’s was Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s. Berson quotes the manager of a Spearmint Rhino explaining that each of their locations “is identical in its design, format and presentation,” much like a McDonald’s. Dancers there were trained to “remember a name and use it three times within the first minute” and to dispense a few practiced compliments. According to Berson, the corporate takeover of strip clubs has left only a few outlier (mostly downmarket) clubs in the U.S. and the U.K. These clubs allow strippers to perform what she considers a radical social function, to satirize social codes and to “disrupt norms of femininity.” But since more and more clubs are now corporate, employees must follow a script, acting out standardized erotic norms instead of writing their own. Over and over Berson says the same thing: Corporate strip clubs crush strippers’ self-expression and individualism.

In some ways what’s new about striptease now has less to do with the questions Berson raises about branding than changes in who’s watching it. Until the 1990s, most audiences were men; now they include women and genderqueer individuals. These new audiences support—or demand—different styles of performance, many of which were not even imaginable a decade ago. Although uniformity reigns in some areas, it has not even begun to take hold in others, and it will take another generation of performers to define “dancing sexy” for themselves.