When you strip away all the surrounding clatter that’s now attached to Crash—the legend of its surprise 2006 Best Picture win, the vicious backlash against its victory—and watch the movie today, what remains striking about this ensemble drama is just how confidently made it is. A filmmaker fully in control of the story he’s telling, Paul Haggis (who also co-wrote the screenplay) wasn’t just tackling racism: He was showing how divisions of all kinds—whether because of age, gender, economic status, or the specific section of Los Angeles where you live—create imperceptible but significant fissures between people. Meticulously crafted and anchored by a superb cast that imbues the film with feeling, Crash is as compulsively watchable now as it was when it was released a decade ago. Also still true: It’s an infuriating, awful movie.

As with plenty of Oscar winners, Crash’s backstory is now almost as well known as the film’s plot. Most have heard that Haggis, an Emmy-winning television writer who worked on shows as diverse as The Facts of Life and thirtysomething, got carjacked in 1991 after going to a screening of The Silence of the Lambs. Holding onto that traumatic experience for years, he woke up in the middle of the night shortly after 9/11, motivated to hit the keyboard and bang out some initial ideas for what would become Crash, a film that follows the exploits of a disparate cross-section of Angelenos over the course of about 24 hours.

In many ways, Crash’s making and its eventual Oscar triumph are an inspiring, unicorn-rare exception to how Hollywood and awards season normally work. Financed independently and shot on a relatively shoestring budget of about $7 million, the project came together because actor Don Cheadle, who signed on as a producer, and his fellow cast members agreed to defer their usual fees, an indication of how passionately those involved felt about the script. Facing off against higher-profile names like George Clooney (Good Night, and Good Luck) and Steven Spielberg (Munich) for Best Picture—not to mention the critically beloved Ang Lee romantic drama Brokeback Mountain—Crash pulled off the upset. This was a true underdog indie film put out by the then-tiny distributor Lionsgate (long before the company got into the Hunger Games business) that managed to claim the industry’s top prize.

And yet Crash remains one of the most derided Best Picture winners, its name practically emblematic of the Academy’s penchant for wrongheaded choices. Despite generally positive reviews upon release, it’s been called the “worst movie of the decade” and the worst Best Picture winner ever. Viewed ten years later, all that vilification isn’t entirely fair. In the age of #OscarsSoWhite, give Crash credit for being one of the few recent Oscar champs to make characters of color not just supporting players but central figures in its drama. And then lament that Haggis’s faith in his earnest, melodramatic material belies how misguided the entire project is.

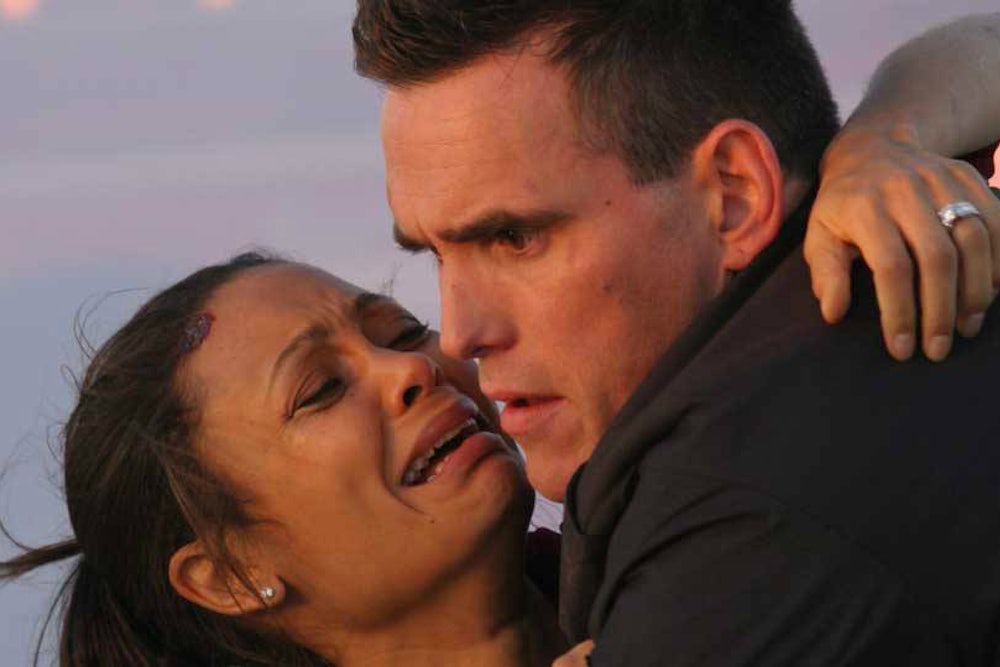

Moving between Brentwood, Downtown and the Valley, Crash lays out what appear to be separate storylines until it becomes clear how these characters are connected in our tidy little moral drama. Cheadle’s emotionally closed-off cop is actually the older brother of Larenz Tate’s carjacking brother, who unsuspectingly takes a fateful ride with Ryan Phillippe’s honorable rookie cop, who used to be partnered with Matt Dillon’s bigoted policeman, who ends up rescuing Thandie Newton’s resentful wife from a burning car after he’d earlier groped her during a traffic stop. Insisting that we’re all invisibly linked to one another, Crash makes its case by stacking the deck so that nobody in the movie is just some ordinary, average schlub living his life: It’s not a small world but, rather, a rigged one masterminded by Haggis.

At a moment when race relations and police brutality remain at the forefront of the national conversation, Crash should be as timely as ever. It isn’t. Watching the film now, its depiction of why we can’t all just get along appears maddeningly untethered to the ways Americans actually experience (and, sometimes, help perpetuate) distrust and prejudice. Haggis, who had written the previous year’s Best Picture winner Million Dollar Baby, never claimed to solve racism with Crash, but his movie did something almost as offensive: reduced a societal ill to a narrative device, the grist for convoluted dramatic ironies that could be held up to the audience as cutesy indicators of the crazy randomness of modern life in a big city.

Crash is the sort of movie that, after establishing that Phillippe’s good-guy cop recognizes his partner’s racism, will be sure to balance the cosmic scales later, having him murder Tate’s unarmed character after a tragic misunderstanding just to prove the filmmaker’s thesis that, hey, everybody’s a little bit racist. Haggis has characters hurl nasty epithets at one another, as if that’s the most corrosive aspect of discrimination, failing to acknowledge that what’s most destructive aren’t the shouts but, rather, the whispers—the private jokes and long-held prejudices shared by likeminded people behind closed doors and far from public view. Even though I agree with Haggis that we all contain trace elements of intolerance that even we don’t recognize, Crash never dares to contend with racism’s evil, infectious power—instead, it makes its characters’ regrettable actions so uncomplicated that we don’t see our own similar failings up there on the screen. Despite Haggis’s endless attempts to interweave the lives of his seemingly dissimilar individuals, he never bothers to include the audience in his calculus, allowing viewers to stand outside the drama in order to judge it from a safe perspective. The whole world’s terrible, but thank god us fortunate few in the theater are wise enough to know better.

All the anger directed at Crash, perversely, is a reflection of the film’s assured execution. A movie this exasperating could only have been made by true believers, and you see it not only in Haggis’s elaborate, jigsaw-puzzle narrative design but in the mostly fine cast he’s assembled. For every questionable choice—say, tapping eternal lightweight Brendan Fraser to play the city’s district attorney—there’s a discovery of a new talent, like Michael Peña, who shines in an underdeveloped role as a locksmith. Even characters stuck as shards of dull glass in Haggis’s overall mosaic are redeemed by the performances Cheadle, Dillon, and others bring to them. (And it’s illuminating to see Sandra Bullock, trying to create empathy for her shrewish Westside wife, begin to lay the foundation for the dramatic performances that would later lead to her Oscar for The Blind Side.)

Haggis’s actors are so committed that they draw you into the movie’s simplistic spell—they make Crash just compelling enough for its gimmicks to fully enrage you. And what gimmicks they are. Ten years after its Oscar triumph, Crash still contains two of the most unabashedly operatic scenes I’ve ever seen—Dillon’s rescue of Newton from that burning car, and the slow-motion gunpoint showdown between Peña and a Persian shopkeeper (Shaun Toub)—and while both remain risible, Haggis’s investment in their grandiose, ludicrous poetry is something to see. A more moderate, reasonable filmmaker would have had the good sense to ease up on the throttle, but Haggis’s certainty steamrolls over any consideration of half measures.

That conviction must have been part of the reason Crash won Best Picture ten years ago. Academy voters are just like the rest of us: They know we live in a very complex world rife with problems that seem intractable, and sometimes we’d like just a smidgeon of assurance that we’re not all careening off the edge of a cliff. Into that void stepped Crash, a confident drama that didn’t offer to cure racism but at least promised to neutralize it for two hours through the merits of passionate acting and clever filmmaking. But Crash’s crippling limitations end up serving as a warning against passion, cleverness, and confidence. If not properly monitored, they’re all just forms of self-delusion, the very same quality that allows bigotry and ignorance to flourish. The older I get, the more I prefer not being sure of anything.

For more on the Academy Awards, listen to the latest episode of the Grierson & Leitch podcast:

Grierson & Leitch write about the movies regularly for the New Republic and host a podcast on film, Grierson & Leitch. Follow them on Twitter @griersonleitch or visit their site griersonleitch.com.