New York’s Town Hall is a janky half-decrepit theater founded by suffragists in 1921, famous for hosting Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and more recently, A Prairie Home Companion, coming to you live from the tourist-scrum of midtown Manhattan. I was here in January, to get talked at by Senator Bernie Sanders, democratic-socialist, ranking minority member of the Senate Budget Committee, former Vermont representative in the House, former mayor of Burlington, civil rights activist, husband, grandfather, Jew, and at the time of this writing, contender for the Democratic nomination for president of the United States.

Settling into my seat, I was panicked. I’d received an email from the campaign’s communications staff indicating that today’s speech was going to be the senator’s yuge (huge) speech on the economy—a subject I’ve always found so abstract, so speculatively mad, determined by so many numbers and percentages and decimal points, bound by so many holding companies and corporate ties, that it seemed to hop, skip, and jump over the human and dwell instead amid the empyrean of the unmentionable, or at least undiscussable, alongside such topics as comparative eschatology and the relationship between free will and the godhead. To speak about the economy with any efficacy, or so as to provide any entertainment, the senator would have to take all the ugly, corrupt, almost animal malfeasance that lurks below the shiny machined surfaces of terminology like “mortgage-backed securities” and “predatory lending,” and breathe it into life, into lives, into real-seeming sagas of real people who’d been duped, indebted, and dispossessed—hardworking, American, etc. people who’d lost their savings, and lost their homes, in a tragic confrontation with a cipher.

And frankly, I didn’t think the senator had that in him. Sanders, at least the Sanders I’d been tuned to, cannot tell a story. Though he’s always invoking regular folks, he never names them, and in fact the only folks he ever names are far from regular and are entered into the record strictly for the purposes of citation, or indictment: politicians, military personnel, academics, business executives, and bankers. Sanders has none of (Bill) Clinton’s charm, and regardless of his reluctance to be a deficit spender, less than none of (Hillary) Clinton’s faux charm—that ability, or willingness, shared by Obama and even George W., to give a State of the Union in which the tale is told of a Mr. X who’d worked for X number of years at X type of job, only to get laid off when his employer moved to Mexico or China. And then suddenly, as if by magic, the camera pans to the balcony . . . and there’s Mr. X, beaming along with Mrs. X, and the X children, who have all miraculously benefited from Y and Z policies.

I hate that cornpone crap—but not like Sanders hates it. And his inability, or unwillingness, to crassify like that seems to derive from some deep inner trust in the logical, some sense that if a policy is honest and intelligent enough, it doesn’t need to be justified by a name or face—it doesn’t need to be sold to you. And while this might never be a feasible way to publicize a movie or TV show, let alone a novel or even a work of election journalism, just such an approach might be the only way to get a socialist elected to the presidency.

White Balance

A lot of things have to happen to ensure the successful filming and broadcast of a major address: Electricity has to be adequate; coverage angles and obstructions must be negotiated. There are sound checks. And finally, once all that’s been put to bed, the last thing that has to be attended to goes by the wonderfully polysemic term, “white balance.” Now, it’s important to remember not to trust everything we see, or hear, or read. Perception is relative, as the Sophists and Roger Ailes have always told us; observation skews. Color temperatures, or intensities, are never absolute, but depend on the device sensing them: the rods and cones of eyes, and cameras. This means that they have to be transformed, or, in film terms, “corrected,” into new intensities appropriate to the display medium—say, the sRGB internet, or HD cable news. The color white, that reflector of light, is the simultaneous combination of all colors. This makes white the standard by which all other colors are judged. To “white balance” an image is to ensure that its white looks white. If that’s the case, then all the other colors will look like themselves too. This, at least in film, generally is regarded as positive.

A man mounted the stage, stood between five American flags and a podium, and held a slab of white card stock aloft. He yelled, “white balance.” The camera people, up on risers behind me, adjusted accordingly. Most of the camera people were white. The man holding the card stock was black. Most of the journalists and the volunteers stalking the aisles issuing hashtag instructions were white. The 1,500-member capacity audience included many people holding their own “white balance”-type signs, card stock scrawled with Sharpie proclaiming their debt, their dispossessions. They were a gender-balanced mix of white, black, Hispanic, South Asian, and Arab. They were waiting for a Jew.

Doing Jewish

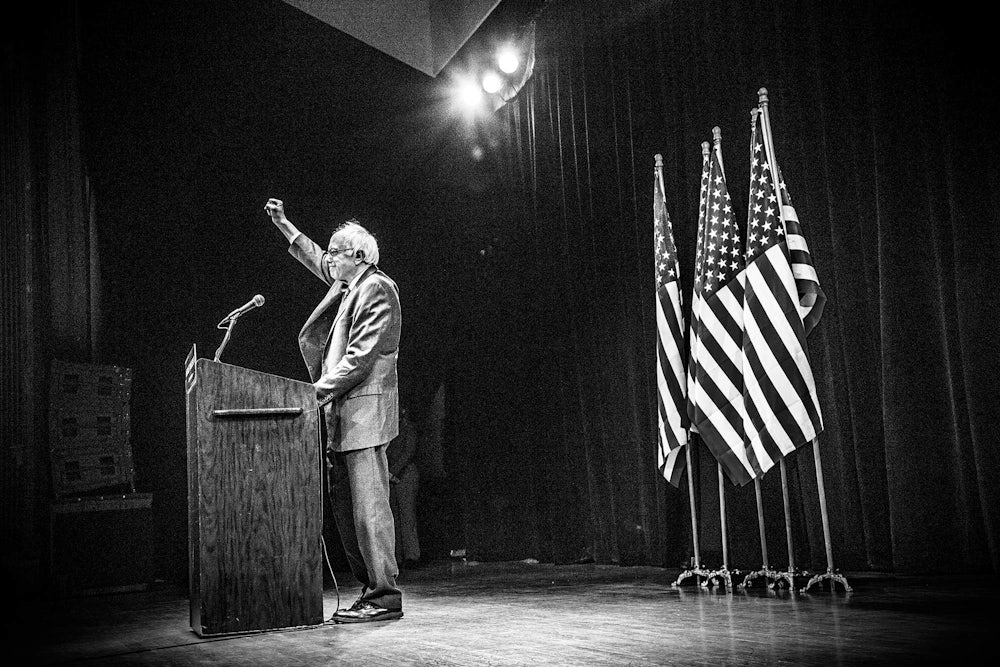

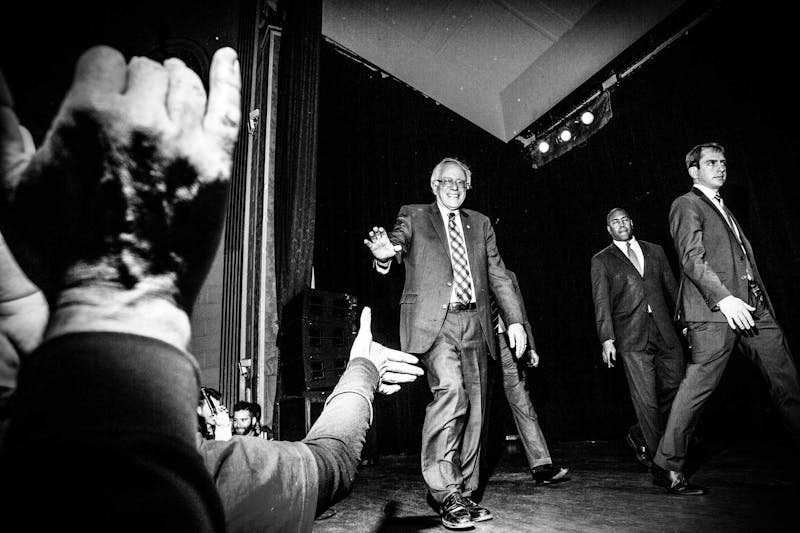

He just comes out, no-nonsense. His suit rumpled, his tie stupid. He barely acknowledges the applause. His hands are up and waving hello but in that don’t-make-a-fuss, don’t-get-up-on-my-account gesture. Sit down already, will you?! The clapping exists in another universe, inaccessible to him, like the laugh track on Seinfeld. Apropos of that Show About Nothing, it makes sense that the great Sanders impersonator has turned out to be Larry David: Sanders’s fellow Brooklynite who, before he played the senator on Saturday Night Live, was a writer on the show who got only one skit produced and a stand-up comic who so notoriously feared and loathed audiences that he used to bail on club dates that were going poorly. Like David, Sanders is a man who came to the front of the camera reluctantly and who always somewhat resents it, or seems to. The front of the camera is where the idiocy lies.

Sanders is not a fluent speaker, and his formulations grate. His speech is barely paragraph-worthy, barely sentence-worthy; its closest model would be the text of a PowerPoint, delivered with a Yiddish krechts. It’s the speech of a Bernie or Bern, never a Bernard. This unrelenting seriousness is embodied by his hair, which is the same white, hot mess it always is and always will be. It’s not merely that Sanders is unconcerned with appearance, it’s that he’s consistently unconcerned, and that consistency reinforces the consistent emphases of his voice, which, in turn, reinforce the consistent phrases he voices. This is a man who doesn’t just stay “regular,” but stays “identical”; whose superficial shambles belie a formidable resolve. He has the fastidiousness of most post–New Deal alter kockers who lay out copies of the Daily News beneath them on the subway, to preserve their pants; he has the rhetorical range of a CPA who spends his lunch break counting heart pills or jelly beans. How many jelly beans, Bernie? Sixty jelly-beans! And by the way, the six largest banks in this country, which “issue two-thirds of all credit cards and more than 35 percent of all mortgages” also control “more than 95 percent of all financial derivatives and hold more than 40 percent of all bank deposits.” And if that’s not enough, try this: “Their assets are equivalent to nearly 60 percent of our GDP.” “Enough is enough,” Bernie says, and the crowd howls.

That last line is classic, in affect: the way he pronounces it with equal parts rage (“Enough”) and resignation (“is enough”). This is a man resigned to his rage, a put-upon, artless, gray-flannelized man whose single-minded fixation on domestic income inequality and financial reform is every bit as enervating and drudgey as it is practical and admirable.

This dichotomy is what makes Sanders fascinating, though it’s not why millions of people, not just Larry David, but millions of Larry Davids in kitchens throughout America, take pleasure in doing impressions of him, or in doing what I’m going to call ostensible, or displaced, impressions. Because despite any exactitude of gesture and phonation—the open-hanging mouth, the tongue-thrust, the accent’s glides, the nonrhotics, the shrugging and grimacing, the peeved shaken fist and wag of the finger—the true thing being impersonated goes unsaid. Larry David does not “do” Bernie Sanders; Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Fallon, and Seth Meyers do not “do” Bernie Sanders; neither do they “do” “pre-gentrification Brooklyn,” nor do they “do” “old man.” Instead, what they “do,” and what they’re relishing “doing,” is “Jew,” and it’s been surprising to me that no one has had the Trumpian schlong to admit this, or to call anyone out on it. Jews know it, and none of them are offended, because Jews embrace Bernie for the same reason that everyone else does; they’re magnetized by one of the only things that America today seems to lack: genuine political conviction, founded in an authentic ethnic identity that can be read as white, but that isn’t racist.

The Racial Politics of Yuge

It’s become fairly clear, and I hope not just to me, that white people in this country have gone crazy. Granted, an apocalyptic belief in the final, definitive loss of 400 or so years of economic and cultural supremacy will do that to you—the fall has been long in coming; masters of the universe should’ve been better prepared. Instead, they act stunned. And to cope with that loss, as well as to cope with the fearmongering of Fox News and right-wing talk radio, which promises them Muslim terrorists in every closet and under every bed, they—or an insanely significant cohort—seem to have given themselves over to the worst sort of race-baiting and anti-immigrant nativism, under the guise of making or keeping America “great,” which is to say, making or keeping America “white.”

What this requires, besides bigotry, is the valorization of a white identity that seems strong enough to counteract the deracinating and emasculating forces of capitalism and what bigots take to be the outrageous sense of entitlement, propensity for violence and crime, and the outsized sexual appetites, of Mexicans (by which they mean all Latinos) and blacks. What I’m talking about, of course, is Trumpism: a cult led by a racist, or a man who plays a racist on TV, who also revels in emphasizing his outtaborough tough-guy cred, though the truth is he’s neither a Belfast brawler nor a Neapolitan mafioso, but the rich-kid scion of a millionaire family of German descent from so far out and leafy in Queens that it’s basically Nassau County, Lawn Guyland. Still, he talks trash like a corner guy. A hood.

It stands to reason, then, that liberals become yugely pleased when they encounter a white liberal in whom they can deduce an equivalent, or, honestly, more genuine and utterly sane version of that same authenticity. Sanders knows this, or at least his advisers do, and in the address produced for Town Hall they have advantaged this asset by interlarding slogans from the Occupy Wall Street Slogan Generator, verbal barrages in a style I can only call Aaron Sorkin joins the IRS, with myriad opportunities for Sanders to use, abuse, and redefine Trump’s favorite pet verbiage:

Wall Street executives still receive yuge compensation packages. . . . Wall Street cannot continue to be an island unto itself, gambling trillions in risky financial instruments, making yuge profits. . . . A handful of yuge financial institutions simply have too much economic and political power over this country. . . . Unlike big banks, credit unions did not receive a yuge bailout. . . . Wall Street makes yuge campaign contributions. . . .

The substance of Sanders’s remarks is lost in these moments. All anyone hears is a yawp truer to the idealized New York street than Trump’s. Instead, what they hear is that word used negatively: With Sanders, huge is bad. Enormous bank, bad. Huge deficit, bad. The word has become so big that it must fail. A person in front of me—a black person—leans over to another black person and whispers the word in her ear. They turn to face each other and grin. This is nachas.

Jewish Power

Everything I’ve written so far is predicated on two assumptions I’m not sure I want to defend: One is that Jews in the American context both are and aren’t white people; the other is that I have some understanding of what Jewishness means, or is signified by, in the mind of Bernie Sanders, who was born on September 8, 1941—a.k.a. the day that Hitler began the disastrous encirclement of Leningrad—and who grew up in a three-and-a-half-room, rent-controlled tenement apartment off Kings Highway, in Brooklyn, the second and youngest son of a Yiddish-speaking traveling paint-salesman father who’d emigrated from Poland and lost most of his family to the Nazis, and of a first-generation American Jewish homemaker mother who’d spent her childhood afflicted with rheumatic fever and who died during a heart operation at the age of 46.

To be sure, the senator himself, whose formal involvement with Judaism began with Hebrew school and a bar mitzvah in the ’50s and appears to have faded after a ’60s stint in Israel picking apples on a kibbutz, hardly wants to talk about that heritage. Neither in speeches, nor in interviews. When I ask about this reticence—not to Bernie directly, but his support staff—I get nothing, except the sense that about half the staff I’ve met is Jewish. Sanders’s 1997 memoir, Outsider in the House, mentions his Judaism only twice, once to characterize the ethnicity of his childhood neighborhood and once to characterize the ethnicity of his parents.

When Sanders was confronted with the evangelical Zionophiles of Liberty University, whom he addressed on Rosh Hashanah last year, he gave brief bland quotes pertaining to spiritual beliefs and to the social-welfare-and-justice philosophies of Judaism. However, more frequently, when pressed about his faith—or what he would do to combat Islamophobia, as he was at George Mason University a month later—he brings up the Holocaust, and the importance of elections, noting that Hitler was elected, after all. Neither of those approaches hold much meaning for American Jews, who, like most Americans, are more concerned with this country’s ghettos, and the concentration camps it’s running in Guantanamo Bay and on the Mexican border, than with rehashing any foreign martyrdom. To date, Sanders’s most public, but also most parlous, statements on his own Semitism occurred in the first two of his two-person debates with Hillary. In early February, in Durham, New Hampshire, he delivered what was received as an atypically personal closing statement that referred to his father as a Polish (i.e. not a Jewish) immigrant, a descriptor that the Nazis, to say nothing of coeval Poles, would have disputed. A couple of weeks later, at another debate in Milwaukee, Sanders was asked whether he was worried about becoming “the instrument of thwarting history” (Hillary’s ponderous, self-thwarting, self-fulfilling prophecy-phrase), by postponing the election of America’s first female president. Sanders responded: “From a historical point of view, somebody with my background, somebody with my views, somebody who has spent his entire life taking on the big money interests, I think a Sanders victory would be of some historical accomplishment, as well.”

It takes a village, but a village of rabbis, to interpret this statement, given its semantic sleight—its impersonality (“somebody”), ambiguity (“my background,” “my views”), and utter alienation from the self (the climactic third-person “Sanders victory”). Who wouldn’t be confused as to whether a Sanders victory would be of “some historical accomplishment” as the triumph of an ideology, or of a Jew? Which is to ask, cynically, which Sanders is the more electable: the Eurocratic redistributionist, or the Ashkenazi son of the commandments? Which revolution was Sanders promising, the one that takes on Wall Street, or the one that takes on prejudice? Was he demanding Jews be counted among minorities in America, or was he tacitly acknowledging that his white maleness was costuming for his ethnic status and so offering a sly critique of our culture of superficial tokenism?

The ambivalence of this statement marks the man who made it, and not, ironically, President Obama, as the commanding code switcher in chief of contemporary politics. I’d argue that Obama never has delivered a statement to the American public intended to be received one way by whites and another by blacks. Hillary never has and never would deliver a statement that meant one thing to women and a whole entire other thing to men. However, Sanders’s “historical accomplishment” was taken to mean “the first Jewish president” by Jews and “the first democratic-socialist president” by the 97.8 percent of the American populace that isn’t Jewish. I’d even hazard that this was how Sanders intended it to be interpreted, and that this double meaning encrypts a private as much as historical truth that for modern Jewry the Left may be the mightier birthright, its social-policy compassion and anti-discrimination imperatives constellating an identity that supersedes any other—a replacement for Judaism even more Christian than Christianity.

As Sanders surely knows but would never discuss, socialism—and its legislation at the national, or universal, level as communism—represented the most provocative and ultimately most poignant attempt by Jews to integrate into Christian society since the emancipations of the Enlightenment. Throughout the Middle Ages, Jewish political involvement was limited to what amounted to extortion: Confined to ghettos, confined to certain occupations, forced to dress according to the sumptuary laws, and perpetually vulnerable to the depredations of hostile populaces, Jews were organized into communities, which were permitted a token degree of autonomy, and forced to pay for protection. They were compelled to lend, or give, money to benevolent regents, who sometimes spared and sometimes slaughtered them. That’s why the republican revolutions of Enlightenment Europe impacted the Jews more culturally, or commercially, than politically: Their upheavals meant that more sons of moneylenders were allowed into schools and allowed to ply other trades, though justice, as always, was gradual, and far from global. It fell to socialism, then, to fire the Jewish political imagination, with Marx declaring, in his 1844 review of Bruno Bauer’s The Jewish Question, “The question of the relation of political emancipation to religion becomes for us the question of the relation of political emancipation to human emancipation.” In other words, the true struggle didn’t consist of persuading a certain government to let a certain citizen-race freely practice its religion; it consisted of persuading all citizen-races to surrender their religions and join together to freely practice universal governance. It was Marx’s conceit that under capitalism all peoples had become “Jews”: forced by dint of social, but predominantly economic, inequalities to act entirely out of what he characterized as “practical need” and “self-interest.” Marx’s money lines: “What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money.” He concludes: “Emancipation from huckstering and money, consequently from practical, real Judaism, would be the self-emancipation of our time.”

Now, it’s all too familiar, and all too cheap, to mention, how that hope died: in Sovietism, amid the show trials and gulags. Even as the Holocaust’s carnage factories were starting to churn, an exiled Trotsky continued to censure Zionism, declaring, “Never was it so clear as it is today that the salvation of the Jewish people is bound up inseparably with the overthrow of the capitalist system.” To summarize the Jewish anti-Semitism lurking behind nascent socialism, just apply Marx’s description to Trotsky’s prescription: To Marx, to live under “capitalism” was to become “a Jew”; while to Trotsky, “Jews” could only be saved by destroying “capitalism,” which is to say, they could only be saved by destroying themselves.

What both Marx and Trotsky, not to mention Lenin and Stalin, were proposing was that Judeo-capitalism must evolve into revolutionary socialism—or into communism, as a successor to the dream of Jewish autonomy-oligarchy-kleptocracy. What would redeem this self-hating morass of identity synecdoche and self-eradicating metonymy was America, a country ripe for personal or racial or religious reinvention, in which the transformational procedures that caused European Jews to de-Judaize themselves into “socialists” and separate themselves from their co-religionists by branding them “capitalists” was reproduced by nearly every immigrant ethnicity: Italians, Irish, Russians, etc., and eventually by the nation’s disenfranchised—blacks—who recognized that socialism had been crusading for emancipation and desegregation well before those most basic civil rights had been enshrined as American law.

Nearly all of the major figures who enabled this integration through reidentification, who went down like Moses into the rail yards, packing plants, and sweatshops, and brought socialism to America, were Jews: Daniel De Leon (1852-1914), a Sephardic immigrant from Curaçao and the forefather of industrial unionism, became the leader of the Socialist Labor Party of America and a three-time failed candidate for governor of New York; Samuel Gompers (1850-1924), an immigrant Jew from England who was the first president of the American Federation of Labor; Victor L. Berger (1860-1929), an immigrant Jew from Austro-Hungary, who founded the Social Democratic Party of America, converted Eugene V. Debs, who had been a Democratic member of the Indiana General Assembly, to socialism, and became the first socialist elected to the House; Morris Hillquit (1869-1933), a Jewish immigrant from the Baltics, who co-founded the Socialist Party of America and was a two-time failed candidate for the mayor of New York City and representative of New York’s 9th congressional district—Sanders’s birth district; and Saul Alinsky, the Chicago-born codifier of community organizing, who influenced Sanders’s grassroots-collectivization campaigning (and, parenthetically, served as the subject of Hillary Clinton’s undergrad thesis). These Jews, who established American socialism, did so in an adopted language. Their main rhetorical twist was to insist that “democracy”—lowercase “democracy”—didn’t exist, except as a lexical superstition that meant “capitalism.”

Money Libel

This revalencing, however, regardless of its aspiringly assimilated American socialist pedigree, might still serve as yet another explanation for why Sanders is loath to discuss his Judaism: Money is at the center of his platform. He stood onstage in New York, three blocks from the Bank of America building, seven blocks from Morgan Stanley headquarters, eight blocks from JPMorgan Chase, eleven blocks from Citigroup, and accused those and other banks, and the credit-rating agencies, and the regulatory agencies, not just of criminal negligence but of having done deliberate harm:

Greed, fraud, dishonesty and arrogance, these are the words that best describe the reality of Wall Street today.

The entirety of the formula reminded me of the High Holiday liturgy, when Jews stand in front of one another, and in front of God, to enumerate their sins and repent for them: Greed (beat your breast), fraud (beat it), dishonesty (beat it), and arrogance (beat it). I understand this characterization betrays my own sensitivities more than Sanders’s, but still I couldn’t avoid the association, or the suspicion that even while he was accusing, he was also atoning. But for whom? And for what?

A confession: The fact that there were no pogroms in this country after the 2008 financial collapse still astounds me, and almost had me convinced that anti-Semitism was on the wane in America, until I was reminded of the equally astounding fact that no goyish bank CEOs were shot or stabbed or beaten or kidnapped in the aftermath. And though Jewish men are seen as disproportionately represented in bank boardrooms, at least as disproportionately as they’re represented on bookstore shelves, and in pairings of non-Asian men with Asian women, the truth remains that the vast majority of bank CEOs are goyim, not to mention that the largest bankruptcy to result from the crisis—indeed, the largest in American history—was perhaps Wall Street’s most historically Jewish firm, Lehman Brothers, which went to its grave with $613 billion in debt.

Still, pockets—empty pockets—of anti-Semitic tropes still fester: web sites dedicated to the kabbalistic significance of the number 613 (the number of mitzvot, or commandments, in the Torah), and to the Zionist Occupied Government perpetrated by Lloyd Blankfein at Goldman Sachs; Ben Bernanke was chair of the Fed; Robert Zoellick, also at Goldman, headed the World Bank. Sheldon Adelson ran, and still runs . . . Sheldon Adelson. Jews comprise around 2 percent of the U.S. population, yet over 40 percent of U.S. billionaires. . .

This money libel, in which Jews are accused of draining money from world coffers, is the modern version of the blood libel, in which Jews were accused of draining the blood of Christian babies for ritual use, which itself was a medieval renewal of the ancient accusation that Jews were the killers of Christ. The metaphoric equivalencies, between blood and money, money and Jews, coruscate from under the slander: Jews, who murdered the child of God, were punished and condemned to wander, or rather, they were forced to circulate, and so to conceal their identities, to convert or exchange their identities; in every situation, they had to remain fungible. In sum, Jews move like money moves, and their Judaism, like all valuta, is an arbitrary principle, both race and religion yet neither—always in transit, always redefining its worth, capable of taking on all forms and no forms, like their God.

The thing is, while I’m quite certain that Jews don’t hold Easter-time baby-murdering ceremonies, nor do they control all world events, I’m not sure that the poetry—the metaphors, again—behind the money libel is unfair, or wrong. Jews have always been mutable, and made trades. They’ve always passed, or tried to pass—as Christians, as socialists, as white. Some of us even broke out of Brooklyn poverty, sat in to integrate the University of Chicago, marched with Martin Luther King Jr., moved to Vermont to dabble in the counterculture, and convinced a bunch of libertarians with guns that we were enough like them to elect us mayor of the state’s largest city, and then to send us to Congress and even, who knows, beyond.

Deflation

Here’s Sanders’s chief speech technique: He puffs the audience up into a frenzy with all variety of denunciations, and then—he lets the air out . . . whoosh. So many of his policies seem like deflations—reductions of banking influence, sure, but also letdowns, paltry punch lines to elaborately setup jokes.

For example, after railing against the banks for a few impassioned minutes, he says that under his administration, he’s going to go all (Teddy) Roosevelt and bust them up. How’s he going to do it? Are you ready?

Within the first 100 days of my administration, I will require the secretary of the Treasury Department to establish a “too big to fail” list of commercial banks, shadow banks, and insurance companies whose failure would pose a catastrophic risk to the United States economy without a taxpayer bailout.

A list! Note where the stress lies: not on the breaking, the bashing, the smashing, the pleasure of revenge, but . . . on a piece of paper! As Spielberg might remind us, “The list is life.”

Another few impassioned minutes are spent lamenting the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, which, as Sanders explains, disentangled the activities of commercial and investment banks. What’s he going to do it about? He’ll reinstate it, with new provisions!

But instead of outlining what those new provisions might be, he instead credits Elizabeth Warren with having conceived them, or introduced them, and then delves into a history lesson on how the original act was passed under (Franklin) Roosevelt but repealed under (Bill) Clinton. He concludes the non sequitur by quoting former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich at length, and in doing so once again demonstrates his penchant for referring to himself in the third person:

Bernie Sanders says break them up and resurrect the Glass-Steagall Act that once separated investment from commercial banking. Hillary Clinton says charge them a bit more and oversee them more carefully. . . . Hillary Clinton’s proposals would only invite more dilution and finagle.

Yes, “finagle.” Which, though it’s technically derived from Old English, has never sounded more Yiddish.

More? Sanders goes on a rant about interest rates, about bank fees, the rape of the middle class. To quote Chernyshevsky, “What is to be done?” Sanders says he’s going to order a cap on ATM fees at $2! Or, to be precise, two dollas!

One last? Like an amateur observational comic, he asks the audience if they’ve noticed that banks are making more money than ever, but when you need a bank in your neighborhood, you can never find one. What. Is. Up. With. That? If you want a loan, you have to go to a payday lender, who entraps you in a debt cycle. So, nu? Sanders would empower all U.S. post offices to offer essential banking services.

This was the most intricately signifying stretch of his performance, as he seemed to be doing Larry David doing him, but doing the material Seinfeld might try out in a guest appearance at a civics class on his child’s Take Your Father to Work Day. Of course, he wasn’t. Sanders wasn’t doing anyone, not even himself. This wasn’t about him, because nothing is.

This is about how lists and ATMs in the post office are going to save America.

Usury

Nothing could’ve prepared me for what came next—the ultimate complication of my emotions, and the one statement that will forever prevent me, who makes judgments about everything, from ever being able to decide whether Bernie Sanders doesn’t care about his lack of polish, or doesn’t even recognize his lack of polish:

If we are going to create a financial system that works for all Americans, we have got to stop financial institutions from ripping off the American people by charging sky-high interest rates and outrageous fees. . . . The Bible has a term for this practice. It’s called usury. And in The Divine Comedy, Dante reserved a special place in the Seventh Circle of Hell for those who charged people usurious interest rates. . . . Today, we don’t need the hellfire and the pitchforks, we don’t need the rivers of boiling blood, but we do need a national usury law.

OK, then. Usury. The derivation is Latin, usuria, from usus, past participle of uti, “to use.” Usury means demanding compensation for the “use” of money. It means, in contemporary terms, “charging interest.”

Sanders has the literature correct: The Bible proscribes usury, but what he failed to mention—what he doesn’t seem, again, to either care about or recognize—is the fact that this proscription allowed the Roman Catholic curia’s various inquisitions to prosecute it as a heresy, punishable by death. Of course, moneylending was one of a handful of occupations that Jews were permitted to engage in, or, in not a few cases, coerced into engaging in, during the Middle Ages, which makes it understandable why noblemen and merchant borrowers would be interested in criminalizing interest. This made the money they were borrowing essentially free, and the moneylender would have to lend on the black market to turn a profit. Dante condemns this practice, that’s true, and relegates usurers not just to the Seventh Circle, but to a subcircle of the Seventh Circle, the lowest of the low: to be harried by the monster Geryon and tortured below the suicides and murderers, amid the sodomists and blasphemers. I wonder whether Sanders would agree with the Florentine poet’s stance on men who have sex with other men, men who use the name of God in vain, and men who off themselves. (To be fair, I presume he’s on board with being anti-murder.) I also wonder whether Sanders shouldn’t have chosen a less-charged, less-invested-with-peril name for his proposed legislation—a name that wasn’t used as a virtual synonym for crafty Jewish malice for over a millennium and a half. What about the No Outrageous Fees Act (NOFA)? Or the Lower Interest Rates Regulation (LIRR)? I mean, couldn’t one of his volunteer redshirts from Harvard/Yale/Sarah Lawrence have googled “usury,” just to gauge how fraught that term might be, especially from the mouth of a Jew? Or maybe the requisite googling was done, and Sanders intends to provoke, or just can’t be bothered?

The great artwork concerning usury Sanders leaves unquoted: Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. And it was at the moment that he pronounced the word again that I had the sense of being present at a new and very skewed production.

Sanders stood ragged on the creaky stage of Town Hall, in the heart of not Venice but another water-bound Serene Republic. He spoke with the same zeal we expect from Shylock, had the same demands for justice, the same ludicrous faith in the judiciary, and even—I swear—some of the same desires.

Here’s the plot: This country’s middle class, represented by Sanders/Shylock, has given a loan, is coerced into giving a loan, to Antonio, who for the purposes of this version will be played by the banks. This loan is in the form of a bailout. When it comes time to repay the loan, the banks refuse, claiming that they can’t, which only means that they won’t, and so Sanders/Shylock hauls them to court and demands repayment of his bond. That bond, though it’s merely symbolic, is also human flesh, and so it’s deemed too much—too beyond the pale—not just against the law, but also against natural law. The banks claim that to deprive them of their flesh would be to deprive them, and so the Republic, of life: Shylock, in his bloodlust, must be a savage. The play ends—Shakespeare’s original play ends—with Shylock on the skids, condemned to wander, without a family, a business, a home.

Exit Bernie, taking no questions:

Follow not;

I’ll have no speaking: I will have my bond.