Far too much of the Democratic primary has been consumed with determining the boundaries of what is and is not serious. Four former chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers under Presidents Clinton and Obama provided the latest example this week, writing an open letter to castigate a fellow economist, Gerald Friedman of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Friedman conducted a study of how the economy would react over the next ten years if Bernie Sanders’s entire program—free college, universal health care, new infrastructure spending, an expanded Social Security, the works—were adopted. And it included some very optimistic numbers: the creation of 26 million jobs over the next ten years, annual economic growth of 5.3 percent, and a return of the labor force participation rate back to 1999 levels. The Sanders campaign didn’t appear to solicit the Friedman study, but it has been citing it to the media.

The Democratic CEA chairs—Laura D’Andrea Tyson, Christina Romer, Austan Goolsbee, and Alan Krueger—believe these numbers undermine their efforts “to make the Democratic Party the party of evidence-based economic policy.” They add: “These claims undermine the credibility of the progressive economic agenda and make it that much more difficult to challenge the unrealistic claims made by Republican candidates.”

I don’t feel it necessary to defend Friedman, though it’s worth pointing out that his economic growth numbers would simply eliminate the GDP gap that was created by the Great Recession and was never filled in the subsequent years of slow growth—which should be the goal of public policy, however “extreme” it sounds. What I do want to challenge is the idea that there’s one serious, evidence-based way to perform economic forecasting.

The truth is that most economic forecasts that look several years into the future are flawed, almost by definition. This is a sprawling country with countless different economic inputs and knock-on effects that are incredibly difficult to accurately predict with a model. Unexpected exogenous events and misinterpreted implications can make forecasts vary sharply with reality, no matter how carefully they’re constructed. There’s no right or wrong way to divine results from policies, and saying so actually makes you look far less evidence-based than you think. The best example of this comes from the reports of these four CEA chairs themselves.

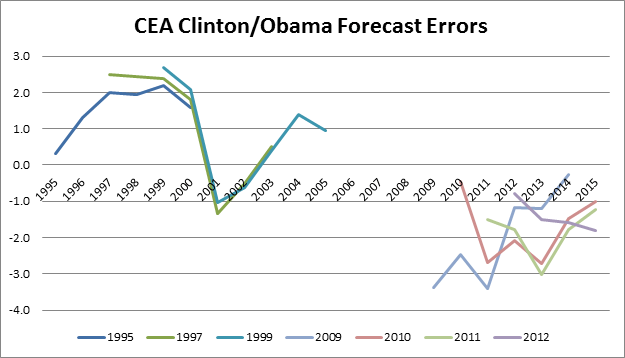

Every year, the CEA puts out the Economic Report of the President (EROP), which includes projections for future economic growth. For example, the 2010 EROP, overseen by then-Chair Christina Romer, made real GDP projections of 4.3 percent in 2011 and 2012, and 4.2 percent in 2013. This was wildly optimistic. According to Federal Reserve Economic Data, the actual real GDP growth rate in 2011 was 1.6 percent; in 2012, 2.2 percent; and in 2013, 1.5 percent.

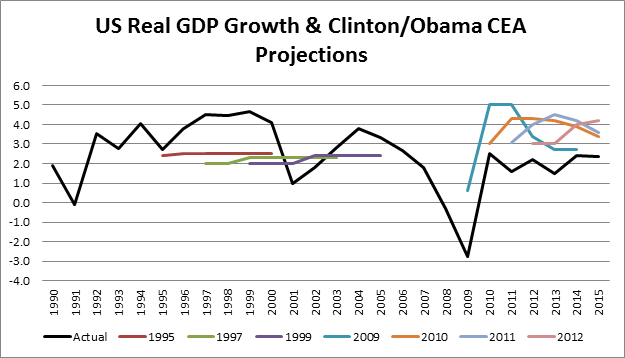

In fact, if you plot the real GDP growth rate against the projections of the Clinton/Obama CEA chairs, you’ll find that they’re consistently wrong by a fairly wide margin. In the 1990s, Laura D’Andrea Tyson wasn’t optimistic enough; in the Obama era, Romer, Goolsbee, and Krueger always over-estimated. (The first chart shows the discrepancy between real GDP numbers and the projections; the second depicts the size of the errors.)

Let’s remember that the CEA has a full staff and the weight of all the data-gathering resources of the U.S. government behind it, compared to one economist in Massachusetts playing with hypothetical models. And yet the CEA still gets it wrong routinely. Which is fine—history tells us we should not expect such precision. But let’s not allow one subset of Democratic economists to take the high road of “evidence-based” mathematics when they’re all throwing darts at a board.

The most recent high-profile example of a wildly optimistic forecast of a specific public policy stemmed from President Obama’s economic stimulus package. Romer and Jared Bernstein released a job impact report of the stimulus in January 2009, claiming that the unemployment rate would peak at 8 percent and start to fall by the third quarter of 2009. We later learned that unemployment peaked at over 10 percent, and was still in that range near the end of 2010 before falling.

The rosy assumptions about the stimulus belied Romer’s earlier studies of how much federal spending it would take to fill the “output gap” from the Great Recession. She initially put the number at $1.7 trillion-$1.8 trillion, but during the transition period between the end of Bush’s term and the beginning of Obama’s, Larry Summers dismissed her findings, most likely in a bid to prevent Congress from getting sticker shock. So Romer revised her own numbers down to $1.2 trillion. President Obama never even saw that compromise figure; Summers stripped it out, leaving a topline figure of $850 billion. Eventually the stimulus topped out around $787 billion.

So Romer should have known that a stimulus at less than half of her initial proposal wouldn’t keep unemployment at 8 percent. But she stated that publicly, whether for political expediency or some other unknown reason. It’s OK to get the projections wrong, but not to author obviously optimistic numbers and later condemn a fellow economist doing the same thing as “running against our party’s best traditions of evidence-based policy making.”

I don’t want to pick on Romer. Goolsbee’s claim in March 2007, after the housing bubble peaked and foreclosures began to skyrocket, that “the mortgage market has become more perfect, not more irresponsible” is perhaps one of the worst economic arguments of the past several decades. The point is this: Economic forecasts are a tricky business. They are not a dividing line between “savvy” and “unsavvy” economists, because the allegedly savvy ones get things wrong just as spectacularly and just as often as the allegedly unsavvy ones.

What’s more troubling is how Democratic mainstream economists use these tactics to boot anyone not preaching from the incrementalist gospel out of the serious club. There are problems with Friedman’s projections; it’s unlikely that we will regain the same labor force participation as the late 1990s when the population now is so much older, for example. But the ferocity of the response—from people who have spent their careers making flawed economic forecasts—suggests that the real issue here is that the establishment is uncomfortable with the more far-reaching aspects of the Sanders economic agenda.

Instead of going point by point on those agenda items, the CEA chairs decided to argue from authority, dismissing Friedman’s numbers as prima facie absurd. This “do you know who I am?” style of argument, first off, is just a bad look if the goal is to persuade. But it also ignores how there is no real authority when it comes to making decade-long economic forecasts. Some humility on that front would be in order.