Yonkers, just north of New York City, can be a noisy place. Kendra Rose grew up here—on Ashburton Avenue, which divides the city’s hard-up south from its middle-class north, and then on Beech. Those who know the area know to avoid roads like Beech, Elm, Poplar, Willow and Linden, the notorious “tree streets.”

Rose did well in the Yonkers public schools. But in the middle of 12th grade, she got pregnant and decided to keep the baby. “I had scholarships to four colleges. My mom took it personally that I didn’t go,” she said. Rose, her boyfriend and their infant daughter moved in with Rose’s grandmother, a Jamaican immigrant, in a rough neighborhood of nearby Mount Vernon.

As baby Khyla grew up, Rose craved a better, safer environment for her family. She imagined a prosperous, suburban life and thought about Mrs. Trager, her high school accounting teacher, who wore “classy, buttoned-up suits” and a confident look. Rose got a job in accounts payable at a doctor’s office and started community college. She badgered the Yonkers Board of Education into giving Khyla a spot in School 16, one of the best K-8 programs in the district. Around the same time, Rose and her boyfriend had their second child, a boy they named Khalil.

When the couple split up about two years later, Rose had to find a new place for herself and the kids. She applied for Section 8, a federal program that helps low-income people pay their rent, but was told it could take months or years to exit the waitlist and get approved. In the meantime, she trawled Craigslist for a rental worthy of her ambition and found a spot in a mostly white section of Yonkers. While working full-time, she earned her associate’s degree and started on her bachelor’s. More than half her income went to rent.

Last fall, after four years in that apartment, Rose felt ready for a move. She and her children had outgrown the cramped space, where they battled faulty plumbing, a testy heating system and mice. It was then that she received some unexpected mail. Yonkers Municipal Housing Authority, which runs the local Section 8 program, asked Rose to update her financial information. Another letter followed, then a request for fingerprints. She didn’t know what to make of it until a friend told her that “people were getting approved.”

Sure enough. In November, Rose attended a briefing at the Yonkers Section 8 office, the grim, bureaucratic appendix of a large public-housing complex. She was guided through a packet that included the “voucher,” a kind of gift certificate for rent. There were strict rules: Her voucher was only good for 60 days, so she’d have to move quickly. And it was limited in value: On a $1,600 two-bedroom unit, Rose would have to pay 30 percent of her income (then, about $900), and Section 8 would cover the rest. “I’m thinking, this is my ticket out,” she said.

In theory, she’d be able to take the Section 8 voucher anywhere. The program had been conceived during the Nixon era as a market-based alternative to derelict public developments. Vouchers were designed to function like cash, paid to private landlords in the rental economy. They would break up concentrations of poverty and, by extension, all-minority ghettos.

Rose hoped it would work that way for her. But at the briefing, the Section 8 officer “told us not to tell [landlords] we have Section 8 until we see the apartment,” she recalled. “She was saying, maybe landlords would judge you because you have this voucher, and they may have negative stereotypes associated with it. And, two, maybe she was thinking they’d tried to take advantage.” Rose was told to search online, at GoSection8.com. She soon found that “90 percent of the apartments listed on there are in bad neighborhoods.” As for other referrals she’d received from the Yonkers housing authority, she said, “I exhausted that list the first day. They either didn’t have anything or were in bad neighborhoods.”

A few days later, Rose went through her packet again and found a one-page flier. All it said, in English and Spanish, was:

THE ENHANCED SECTION 8 OUTREACH PROGRAM (ESOP)

20 SOUTH BROADWAY, SUITE 1102

YONKERS, NEW YORK 10701

PHONE NUMBER: (914) 964-5519

FAX NUMBER: (914) 964-6619

She had no idea what ESOP was about, but called anyway. A woman named Beverly Bell answered the phone and told her to come in on Nov. 10. With Bell’s assistance, she hoped, she just might make her deadline of Jan. 4.

For at least 100 years, sociologists and policymakers—from W.E.B. Du Bois and Horace Cayton to Daniel Patrick Moynihan—have debated the relationship between housing and poverty. That some neighborhoods are rich and others poor is a basic fact of capitalism, but the extent to which “neighborhoods broker access to social goods and exposure to environmental harms (PDF),” as one advocacy group puts it, is peculiarly American. So is the enduring overlap between race and economic status.

The Fair Housing Act, like other parts of the 1968 Civil Rights Act, was intended to prohibit discrimination based on race and other demographic categories. Landlords, realtors and brokers could no longer refuse outright to rent or sell property to racial minorities. Desegregation was the goal, yet residential homogeneity continued to be the norm.

In 1966, Dorothy Gautreaux and other low-income renters in Chicago filed a lawsuit claiming that the city and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, had engaged in racial discrimination by clustering public housing in black areas. The plaintiffs won, and HUD and the city were ordered to move African-American families into racially mixed areas. By then, it was the mid-1970s, and they had a new device to do so: Section 8 vouchers. Eventually, some 7,000 people were relocated.

Following the blueprint of the Gautreaux case, HUD launched a program known as Moving to Opportunity in 1993. In several large cities, Section 8 vouchers were used to relocate people of color to middle-class neighborhoods. Similar “mobility” initiatives—federally funded and locally designed—now operate in 15 of the nation’s 2,300 housing authorities. Some, like Baltimore’s, are quite large, benefiting thousands of women and kids. And though research on long-term poverty-alleviation has shown mixed results (PDF), children who moved at a young age have been more likely to finish school and earn higher incomes than those who remained behind.

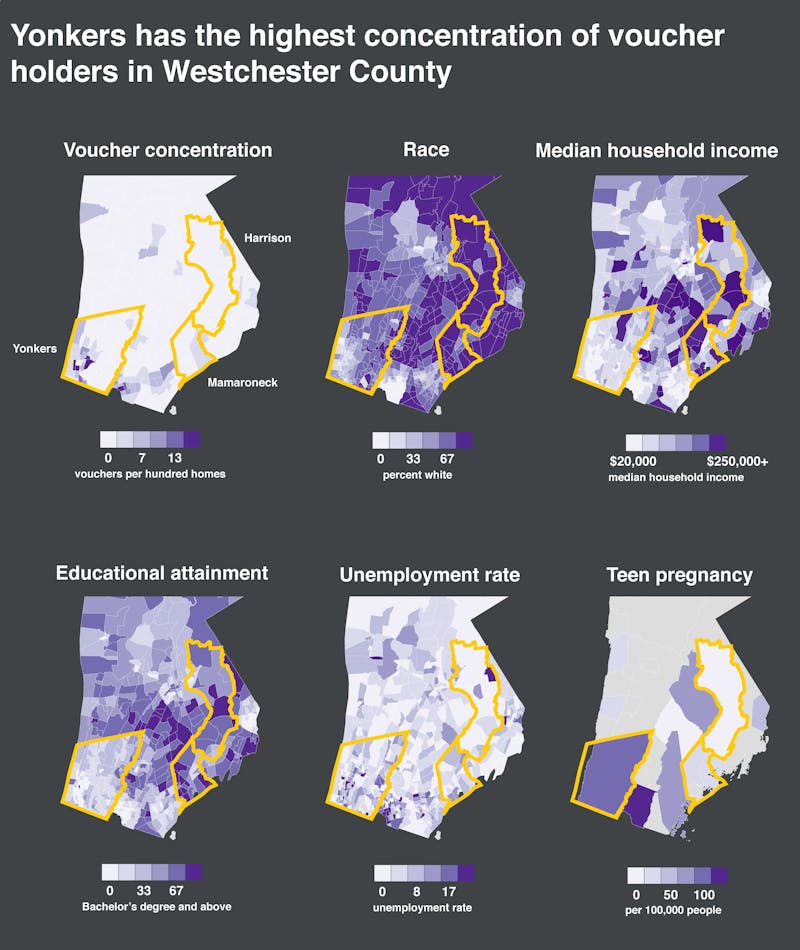

Rose didn’t realize that the number she’d dialed in her Section 8 folder belonged to Yonkers’s very own housing-mobility office. The Enhanced Section 8 Outreach Program, or ESOP, had been established in 1993—the same year as Moving to Opportunity, but through the settlement of a class-action lawsuit against Yonkers Municipal Housing Authority, Westchester County and HUD. Section 8 voucher holders had accused the defendants of “perpetuating the racial segregation of Yonkers” by failing to ensure that vouchers were spent on “decent, safe housing outside of areas of minority and low-income concentration.” The named plaintiff was Carol Giddins, an African-American receptionist with two kids whose apartment was roach-infested and surrounded by crime.

The structure of Section 8 was partly to blame. Federal voucher dollars flow through local agencies incentivized to get people housed as quickly as possible. It’s easiest to use vouchers in neglected areas, where landlords need tenants and neighbors are unlikely to be hostile toward low-income newcomers. In whiter, more affluent neighborhoods, rentals are in short supply and landlords often refuse to take Section 8. Historically, advocates say, HUD has done little to enforce anti-discrimination laws.

Giddins was represented by Jerry Levy, a Legal Aid attorney born and raised in a Jewish enclave of Brooklyn. Levy had gone into legal services determined to make a difference in the lives of the poor. In the 1970s and ’80s, he saw clients all over Westchester County, untangling welfare cases and helping families keep their food stamps. It was good, satisfying work, yet the wins didn’t last. His clients came back again and again. They couldn’t find work. They stayed sick. Their kids went to failing schools. It all went back to where they lived, he concluded.

The Giddins case veered quickly toward settlement, coming, as it did, on the heels of another, more infamous Yonkers lawsuit. As captured in reporter Lisa Belkin’s 1999 book “Show Me a Hero,” and a recent HBO miniseries of the same name, that case alleged that Yonkers had deliberately segregated people of color through the placement of public housing, much like in Gautreaux. The federal court agreed and ordered Yonkers to build a small number of low-income units in white areas of the city. Local officials refused, bolstered by residents hurling slurs against blacks and Jews. (One of the lead attorneys for the NAACP, a plaintiff in the case, was Jewish.) But the town houses were eventually built.

Yonkers and Westchester County had no appetite for war in the Giddins case. By 1993, a consent decree was approved, establishing ESOP as one of the first Section 8 mobility offices after Gautreaux. HUD gave ESOP 100 vouchers for families moving out of high-poverty areas, while the city and county provided an operating budget. Bell, who’d made an appointment for Rose, was there from the beginning, and Levy was hired in 2000. It’s been just the two of them ever since.

ESOP no longer has its own vouchers to distribute. It functions instead as an off-ramp from two standard Section 8 programs, in Yonkers and Westchester County. (There are 14 overlapping public housing authorities in the county, many with waitlists thousands of names long.) Applicants lucky enough to obtain a voucher are given the option of working with ESOP. Those who choose the organization are “self-selecting … people who are willing to leave their neighborhood,” said Joseph Shuldiner, executive director of the Yonkers Municipal Housing Authority. ESOP’s mobility work, he said, must be paired with investments in poor communities. “If you don’t spend any money on [bad neighborhoods] and get the upwardly mobile people to leave, then you’ve made the situation worse. … You have to have viable neighborhoods everywhere.”

The ESOP office is on a rowdy downtown block, in an old, art deco bank building with a mechanical elevator dial, the handiwork of a brighter Yonkers. Levy, a voluble, 72-year-old activist, and Bell, a reserved African-American woman who’s lived all over the world, see themselves as stewards of another history. “In America it’s all about race,” Levy said. “Black progress and black civil rights are being delayed.” This belief keeps them going: They’d intended to retire this year, but with no successors in sight, they’ve put those plans on hold.

Since ESOP opened for business, it has helped some 800 families move into “nonimpacted” areas, defined as neighborhoods with very low rates of poverty and a majority-white population. Nationwide, some 2.1 million households benefit from Section 8 vouchers. ESOP has a special budget from HUD, the state and the county to pay brokers fees and higher rents in select ZIP codes. Thus, while an ordinary Section 8 voucher covers rents of up to $1,510 for a two-bedroom in suburban Harrison, ESOP’s limit can be as high as $2,120.

The nonprofit may have grown out of class-action litigation, but its services, and successes, are household by household, rental by rental. Short-staffed and run on less than $250,000 per year, ESOP must choose which clients to serve. “It’s a real give and take with them and us—‘What we can do for you possibly? What do you need?’ Sometimes we find baggage right there at the first interview,” Bell said. She cited an irksome example: People so attached to their animals that they’d sacrifice the chance to live in a superior, no-pet building. Or, Levy added, “we have clients who live in terrible housing, and they see the [new] apartment and they don’t want to take it because their furniture is so big.”

They knew right away that Rose would be a good fit. At her intake meeting, she explained that she was working full-time and getting her master’s on the side; she fretted over her children’s education and spoke of a need for calm. Though Rose knew nothing about ESOP, she liked what she heard from Bell and understood the mission: to give ambitious people of color a chance in high-opportunity neighborhoods. “I know it sounds horrible coming from me, because I’m African American,” she explained, but she wanted everything white suburbia had to offer. “If you move into an affluent area and [the neighbors] see you as a single mother waking up every day and doing what you have to, to see you dressed like you’re going to work, that might break some of the stereotypes that they have about African-American families.”

ESOP will not pay for a unit that’s rundown, overpriced, located in a high-poverty neighborhood or inaccessible for a tenant with disabilities. Public housing and “affordable” developments are similarly off-limits, both because of stigma and geography: The vast majority of the 63 HUD-subsidized buildings in Westchester County are located in poor black or Hispanic neighborhoods. Yet not everyone agrees with Bell and Levy’s vision of Section 8.

Since its founding, ESOP has faced three HUD complaints filed by former clients, in 2002, 2003 and 2006. The complainants (whom HUD would not identify) alleged “discriminatory refusal to rent” and discrimination in rental terms based on disability and familial status. All three grievances were judged groundless by HUD but proved the hazards of an inflexible approach. “We’re pretty much purists here,” Levy said, “almost to our detriment, because a lot of our funding is to get people into apartments, and there are plenty of clients who come in who we can’t move.”

Those who have moved with ESOP seem to be thriving. There’s Tiffani Hardy in leafy Mamaroneck, who delights in letting her young daughter walk home from school. There’s Heidi Sweat, whose children, Asia and Robert Blue, will be among the first in their extended family to attend college. And there’s Carmen Gomez, a Dominican immigrant who raised three successful daughters in quality housing with Levy and Bell’s guidance. Most ESOP clients are African-American mothers.

For Geraldine Halsey, 71, and her grandson, Carlos, ESOP has meant the difference between life and death. In May 2009, the day after his high school prom, Carlos was hospitalized for pneumonia. He was living in Yonkers, confined to the dark, damp basement of his father and stepmother’s house, when he suddenly became ill. He’d used a wheelchair most of his life, but the pneumonia compounded his muscular dystrophy, leaving him in need of round-the-clock nursing care and derailing his college plans. Halsey stepped in and decided her grandson would not return to Yonkers.

She obtained Section 8 on his behalf and found her way to ESOP. She told Levy and Bell that she wanted a place “in a quiet, decent neighborhood—a neighborhood that, when I went there, I wasn’t afraid.” She found one, in a tranquil section of Mamaroneck, and ESOP took over from there. By the time Carlos got out of the hospital, the unit was furnished and ready: a modern, wheelchair-accessible two-bedroom. He recalled thinking, ‘ “Wow, I have my own apartment—so much space. I could see everything. I could see the outside.’ ”

ESOP most recently moved Monica Coaxum, a college student and hospital lab technician, and her 10-year-old daughter, Nyla. Their old place in southwest Yonkers was filled with problems. The windowsills were crumbling, the bathtub would hardly drain, and mice and cockroaches skittered across the warped floor. What happened beyond the front door was harder to fix. Nyla wasn’t allowed to play outside.

Last fall, in a stroke of bureaucratic luck, Coaxum applied for and received a Section 8 voucher. She attended a briefing at the Yonkers housing office, just as Rose would do some weeks later. The staff informed her that she could “live anywhere,” yet offered no leads on available units. A short while later, she met with Levy and Bell and asked them for help.

On January 15, after a brief but taxing search, Coaxum and Nyla settled into the second floor of a large, three-story home near the Harrison train station and Nyla’s new, top-ranked elementary school. The street was quiet, the wood floors level and new, the walls painted peach. Levy and Bell had gotten word of the vacancy and thought immediately of Coaxum. They guided her from start to finish: Bell showed her the unit, inspected it for habitability and demanded repairs from the landlord. Coaxum signed the lease in the ESOP office, and Levy talked her through assorted odds and ends—parking permits, car insurance (Coaxum’s premium dropped substantially upon leaving Yonkers), local taxes, and whether Nyla could walk to and from school on her own.

“I view it as if a corporation is moving somebody from L.A. to N.Y. They say, ‘OK, here’s what we’re going to do for you: tell you about a good place to eat, where the doctors are, where there’s shopping,’ ” Levy explained. “So for my clients, in their world, I make sure the day care’s right, medical insurance, whatever legal problems they’re having with schools, and if there’s a dispute with the landlord, we try to intervene.”

As a rule, Section 8 recipients recertify their vouchers once a year, or whenever there’s a change in income or household composition. This may be their only reason for contacting the local housing authority. ESOP speaks with its clients far more frequently. It has guided some families through two or three rentals over a period of decades. “We become like the family lawyer when they have issues,” Levy said. “The work I do for my clients is the work my parents did for me.” (Bell, too, is an attorney, though she no longer practices.)

“ESOP follows up with families, and that’s valuable. We’ve seen that the post-move counseling has been essential to stay in higher-opportunity areas over time,” said Phil Tegeler, president of the Poverty & Race Research Action Council, a policy group in Washington, D.C. From a taxpayer perspective, “It’s a small price to pay for benefits—access to high-quality schools; health and employment; for young kids to be out of stressful, high-crime environments for their cognitive development and emotional development.”

Her children’s welfare was Rose’s top concern. In Yonkers, four-year-old Khalil was in preschool and daycare, learning his ABCs; Khyla, ten, was earning good grades and taking up the saxophone. Rose wondered, though, if her daughter “was doing well because of the mediocrity of the school or because she has a high intellect.” How would Khyla fare in the better funded, more competitive districts ESOP had gotten her to imagine?

Bell promised to look for vacancies, while Rose continued her own search. The market was much bleaker than she’d expected, and many landlords told her upfront that they would not consider her voucher. “I always wanted [Section 8]. I was a single mom with two kids paying my bills on my own,” she said. “Now I realize it’s a little bit of a hindrance, because a lot of apartments don’t accept it. A lot of landlords turn their nose up at it. It’s really hard to find an apartment on this program.”

Rose gave up on GoSection8.com but continued to scour Craigslist, nonprofit housing lists, and the local pennysaver. Scrawled notes listing names, phone numbers, addresses, and rents piled up in her purse. Every day, she contacted brokers and landlords, interrupted only by Thanksgiving, then Christmas, then New Year’s Day. She took a new job, as a full-fledged accountant, and adjusted to a longer commute. Her pay jumped from $36,000 to $50,000, yet she remained eligible for a voucher: Unlike most anti-poverty programs, Section 8 allows families to earn more over time.

In two months, Rose saw about ten rentals in person and made countless calls. Rose refused to live “anywhere there’s trees”—on those infamous roads of Yonkers. “I’d rather live in a studio than a three-bedroom for $1,500 on Elm Street,” she said.

She finally had to ask Section 8 for a one-time extension. They gave her until the beginning of March. “It’s like a puzzle,” she said. “Everything takes time—for the inspector to come out, to pay the full security payment, to show Section 8 you paid the security payment so they release their portion, and hopefully you can get a key.”

Section 8 voucher holders get quickly accustomed to hearing “no.” In well-to-do neighborhoods, landlords cite federal red tape (the annual inspections, delayed payments), bad experiences with previous Section 8 tenants, or the latent wrath of neighbors opposed to anything other than market-rate, single-family homeownership. Realtors say similar things, and play bouncer, Bell said, to fend off unsavory prospective renters.

A few years ago, before Sweat signed her current lease, she contacted a broker showing properties in Mamaroneck. The broker wanted to make sure she would not be bringing “dozens” of men around, and was insulted when Sweat was less than enthusiastic about the available units. In an email to Bell, the broker wrote that she was “shocked” when Sweat declined to see an apartment willing to take Section 8 in Mamaroneck: “I do not have time to waste on lackadaisical non motivated renters who are just thinking about moving.”

Levy believes that the refusal to take Section 8 amounts to intentional discrimination, an untested theory under fair-housing law. But that’s indeed what it feels like for the many ESOP clients who’ve struggled to use their vouchers. “You make choices in life, and you still want to correct yourself and get on track,” said Hardy, the ESOP client raising a young daughter in Mamaroneck. “You’re doing what you have to do to get where you’re trying to be, so why am I only offered apartments in the worst areas?”

There is much damage inflicted by gatekeeping realtors and discriminatory landlords. Yet Bell and Levy see larger, murkier structures at play. Like many wealthy suburbs, those in Westchester County have historically defined themselves in relation to the perceived chaos of the metropolis: crowds, apartments, and poverty. The villages and towns north of Yonkers—home to Hillary and Bill Clinton, David Letterman, Martha Stewart and many other elites—were designed to uphold the sanctity of the standalone home. Duplexes are rare; apartment buildings even rarer. Zoning boards and homeowners’ associations wield as much power as local governments.

In 2006, the Anti-Discrimination Center, a nonprofit run by attorney Craig Gurian, sued Westchester County for unlawful use of HUD funds. According to the ADC, the county and its many localities had taken $50 million in federal funds intended to promote racial desegregation and economic mobility, while enacting restrictive zoning that shut out middle- and low-income minorities from well-to-do neighborhoods. In 2009, after the federal government took over for ADC as plaintiff, the parties reached a complex settlement. Local officials were directed to reform exclusionary laws and build 750 affordable town house and apartment units in affluent white communities. Westchester County was required to pass an ordinance banning discrimination based on source of income (in other words, Section 8). Even then, Republican County Executive Rob Astorino tried to block the law. Westchester maintains that it’s in full compliance with the court-ordered agreement. And James Johnson, an attorney and former Treasury official who was appointed federal monitor in the case, has mostly backed up the county. (He declined to comment for this article.) Johnson has focused on the construction of the 750 units—without considering their condition or location, or requiring the county to intervene in local zoning decisions, Gurian said. As reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones documented in a ProPublica investigation in 2012, much of the new housing intended to fulfill the settlement is being built in remote, undesirable stretches of the county.

Astorino, a media-savvy former radio host who Levy compares to Donald Trump, has formed his political identity around “local control.” Last July, he held a press conference outside the Clintons’ home in Chappaqua, decrying federal overreach. “Does she think she lives in a discriminatory town?” he asked, rhetorically, of Hillary Clinton. “I don’t. Does she think the Obama administration is being very unfair in attacking her own community? I do.” ESOP’s work has become harder over the years, in part because of Astorino’s policies, Bell and Levy say: They moved just seven families last year and three in 2014; since 2010, their active caseload has shrunk from 120 to 50 clients.

In September 2015, a federal appeals court allowed HUD to strip Westchester County of some $5 million in federal funds based on exclusionary zoning and other violations of the Fair Housing Act. “They provided us plans in the past that said, ‘We’ve looked around and done an honest assessment, and there are [no barriers to fair housing].’ And we’ve said, that’s not what we consider to be an honest assessment,” said Brian Sullivan, of HUD’s public affairs office. Nevertheless, HUD has permitted Westchester’s cities, towns and villages to continue receiving these federal funds—through the state, instead of the county—a policy endorsed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who was HUD secretary under former President Bill Clinton.

Westchester denies any wrongdoing in local zoning practices or problems with racial segregation. According to Astorino’s spokesman, the county is ahead of schedule on building new units and committed to affordable housing. It has partnered with the Housing Action Council, a large, nonprofit developer, and paid the council’s former director, John Nolon, a professor at Pace Law School, to provide fair-housing trainings to dozens of county officials, for a fee of $1,000 to $1,500 per person. The key to achieving progress, Nolon said, is education, not litigation: “To threaten people with a lawsuit was not going to get you anywhere, because you were implying that they were racist and doing something motivated by racial animosity.”

Levy, Bell, and Gurian disagree. Westchester will “change some zoning in some towns, but it won’t be inclusive, where everybody else lives,” Levy said. “They won’t be part of the fabric of the community.” Gurian blames HUD and the federal government for failing to act: “It’s not that the enforcement approach hasn’t worked; it’s that no one has dared to try it.” He doubts that either the 2015 Supreme Court case upholding a basic principle of the Fair Housing Act or HUD’s recent spate of fair-housing initiatives will make much difference for low-income African American families.

This was the part of Rose’s housing search that she could not see. The “no’s” she’d heard from individual landlords and brokers, their skepticism and disdain for Section 8, were the distilled product of a chemical reaction. An explosive mix of HUD rule-making, county governance, federal litigation, local zoning, and history.

She tried to believe it would work out, yet her deadline for using the voucher—extended once and for all to March 4—was approaching. With so many landlords unwilling to even consider Section 8, she started to feel it was “hindering me from finding an apartment,” she said. “Eventually, I may have to just pay $1,500 or $1,650 on my own.”

As January rolled into February, Rose spoke with ESOP three or four times a week. Bell and Levy worked their contacts and searched online, too, though the listings were grim. One day, they looked for two-bedroom rentals on socialserve.com, a website often recommended by local Section 8 offices. Twenty-six units came up that were willing to take vouchers, but nearly all of them had a waiting list, and only three were located in low-poverty areas. “Those are the worst days,” Bell said.

Just before Valentine’s Day, Bell called Rose with a lead. There was a vacancy in Harrison: a renovated three-bedroom with new appliances, a short walk from the local schools. Rose went to see it right away.

The landlords were a husband and wife who were new to Section 8. They were wary at first and asked Rose a number of personal questions, she said. What were her child care plans? Who might her visitors be? Would the children’s father come around? “They did seem to be concerned about me being a single mother,” Rose said. In Yonkers, “I wouldn’t have to put up with the questioning and barriers, but I’d be living god knows where, and the kids wouldn’t be in a good school district,” she told herself.

By the end of the visit, the landlords warmed up to Rose and were willing to make a deal. The apartment was a great fit. Pricey, though; impossible without ESOP. Bell had asked her not to commit right away, so Rose thanked the landlords and drove home, promising to be in touch soon. “I don’t know how I could turn it down,” she said. Though it was far from settled, she let her thoughts race ahead—to the inspection and lease-signing, to the cool metal keys in her hand, to Khyla’s first day in an excellent school.

Editor’s note: This story was co-published with Al Jazeera America.