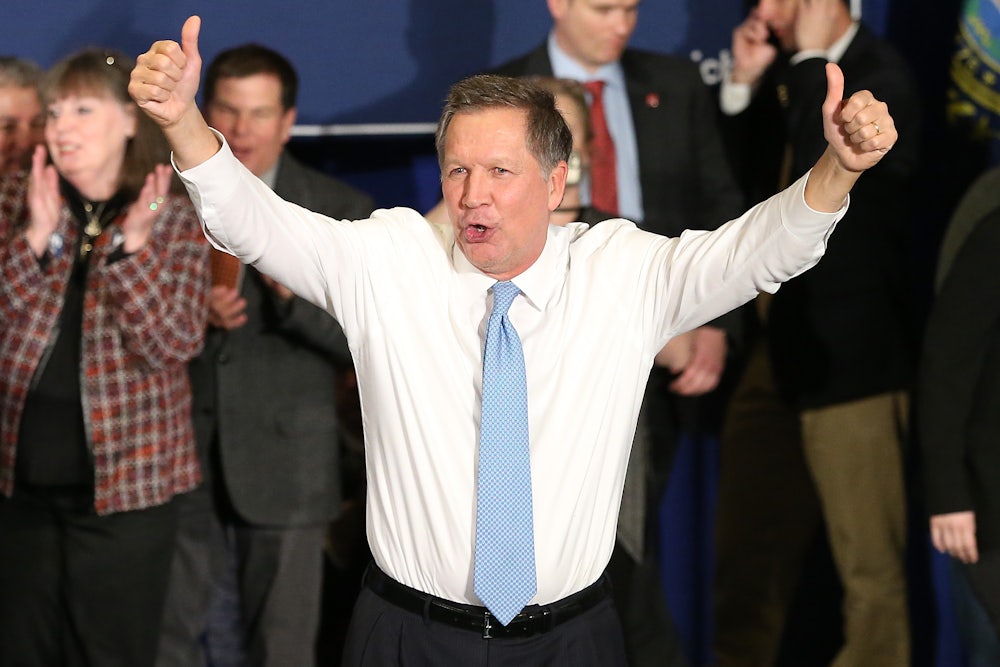

Shortly after 10 p.m. on Tuesday night, John Kasich took the stage in Concord, New Hampshire, for a surprising victory lap. The Ohio governor had come from behind to clinch second place in the New Hampshire primary, and first in the “establishment primary” that provided most of the night’s suspense. “Maybe, just maybe, we are turning the page on a dark part of American politics,” Kasich told his supporters. “Tonight the light overcame the darkness of negative campaigning.” It was Kasich’s chance to introduce himself to the broader American public with the message that had broken through in New Hampshire: Here was the lone positive force in a bitterly divided Republican primary.

Kasich ran a singularly bold campaign in the first primary state, betting that New Hampshire voters would sour on the other establishment candidates—Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, and Chris Christie—who were blanketing television with vicious attack ads in the months before the primary. His gamble paid off, as more New Hampshire Republicans opted for Kasich, the compassionate conservative who’d deemed himself “the prince of light and hope.”

Kasich, who’d said he would drop out if he fared badly in New Hampshire, can now preach his kinder, gentler Republican gospel in the next primary contests. But is there any path to the nomination? Kasich leaves New Hampshire with a bit of momentum, but no money or organization in any state but his own, Ohio, which doesn’t vote until March 15. His big experiment in political positivity will be a far tougher sell as the race moves south for the South Carolina primary on February 20 and Super Tuesday on March 1. And the confluence of factors that propelled Kasich to his surprise finish in New Hampshire isn’t likely to be replicated.

Just last week, Kasich was still languishing in the single digits, on track to become an also-ran in New Hampshire. His late surge stemmed from a near-perfect storm of factors. Rubio sunk in the polls after his disastrous performance at the last Republican debate, giving Kasich an opening to snap up his supporters. He also took advantage of the unusually large number of independent voters who turned out on Tuesday—according to ABC, four in ten. CNN’s Dana Bash reported Tuesday afternoon that Kasich volunteers were calling independents leaning toward Bernie Sanders to ask for their support, likely touting Kasich’s relatively moderate record on Medicare expansion and marriage equality.

But it was the bitter negativity of the New Hampshire showdown between the establishment candidates that gave Kasich his biggest boost. Super PACs supporting Rubio, Bush, and Christie funneled millions into attack ads hitting their closest competitors, including the Ohio governor. Kasich and his affiliated PAC, created an unmissable contrast, aired predominantly positive spots and only hammered the other candidates for their mudslinging.

“We have a lot of candidates who like the prince of darkness,” Kasich told radio host Hugh Hewitt last month. “I don’t spend all my time getting people riled up about how bad everything is.” In a brilliant reading of the New Hampshire electorate, he bet that voters would grow tired of the relentlessly negative ads and the candidates who launched them—so tired that they would support Kasich, whose main selling point is his dogged adherence to positivity.

Kasich’s strong

finish was also a triumph of retail politics. The Ohio governor has long been

all-in in New Hampshire; he’s crisscrossed the state for weeks, holding 106 town halls (the next-closest candidate in town-hall totals was Chris Christie, who held just 72). That kind of politicking can work wonders in New

Hampshire, a small state where voters value face time with the presidential

contenders and candidates like Kasich can rely on independents for support.

But as the campaign moves past Iowa and New Hampshire, the states get larger—and on Super Tuesday, there will be twelve voting at once. Candidates need ground troops to fan out over the states they’re targeting, and pricy campaign ads to spread their message on the airwaves. Kasich has neither.

So now comes his next test: Kasich will have to translate his momentum into a decent showing in South Carolina’s primary on February 20, where Jeb Bush is positioned to perform well in the establishment lane. Kasich intends to target Michigan, where his rust-belt roots and populist message could connect with voters. But its primary falls on March 8. By then, if Kasich has failed to score another surprisingly strong performance in at least a state or two, he may not have the juice to get a hearing from Michigan voters.

Can Kasich’s prince-of-light politics travel? There’s no question that his message will stand out from the Republican pack wherever he goes—but will voters in states like South Carolina find it refreshing or weirdly out of tune? Watching Kasich on Tuesday night, it was tough to imagine a whole lot of South Carolina Republicans nodding and clapping along. Hunched over the podium, the Ohio governor gave a folksy, rambling treatise about the America of

his youth, encouraging folks to hug their neighbors and heal the divisions in

their families. He peppered the speech with lines like, “We all cried a little

bit that night,” and “From this day forward I’m going to go

slower, and spend my time listening, and healing, and helping, and bringing

people together.”

Donald Trump, the actual winner (who’s also miles ahead in South Carolina), could not have delivered a more dramatically different victory speech. “We are going to win so much. You are going to be so happy. We are going to make America so great.” Even his punchy sentence structure conveys an aggressiveness you never see in Kasich’s genial, rambling speeches.

Kasich can only hope that the populist anger the media has been talking about for months proves to be overblown. His strong finish in New Hampshire would suggest that that a solid Republican cohort still wants a moderate as its standard bearer in the general election, one who stands apart from the mudslinging and vitriol in this race. But looking at the winners in both the Democratic and Republican primaries tells a different story: Both Trump and Bernie Sanders railed against the status quo, tapping into a deep-seated anger about the direction this country is heading, and they bested the other contenders by wide margins in New Hampshire.

Polls show that 65 percent of likely voters are worried their country is headed in the wrong direction. Republicans are particularly angry, and they want a strong leader who channels their outrage. That makes it a tough road ahead for a candidate like Kasich, who promised Tuesday night to make America great again—with hugs.