Jeb Bush entered the Republican race for president with reluctance, worrying aloud that his 199os brand of conservatism would look hopelessly moderate to the Tea Party Republicans who have come to form the party’s base in the twenty-first century. As he told friends in 2012, Bush’s own father and even Ronald Reagan would have a “hard time” fitting into today’s GOP. In 2014, as Bush continued to waffle about running, Jonathan Martin reported in The New York Times that he was “grappling with the central question of whether he can prevail in a grueling primary battle without shifting his positions or altering his persona to satisfy his party’s hard-liners.”

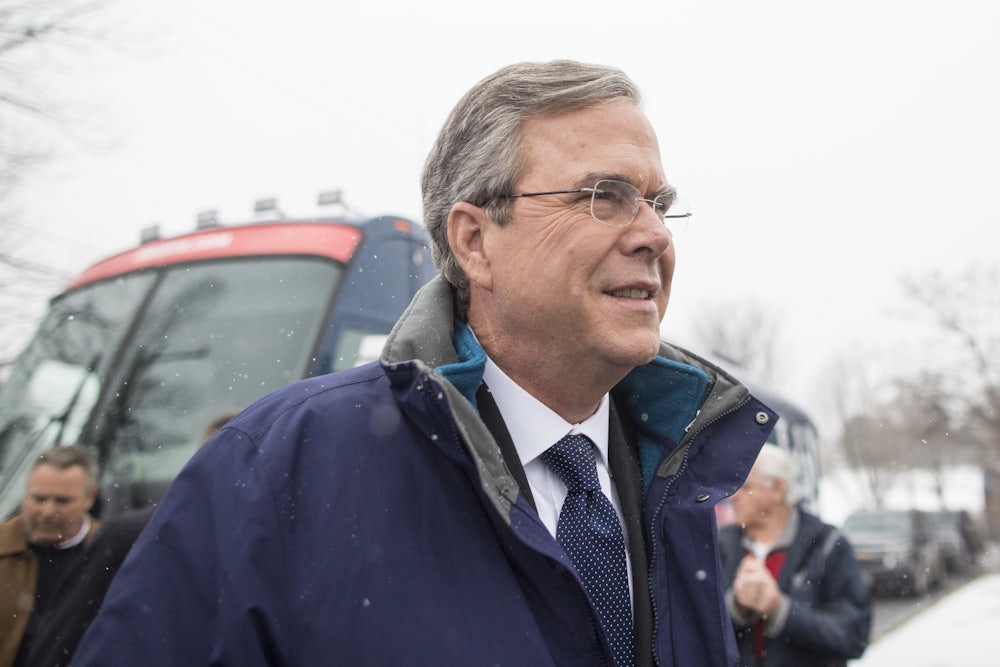

As his flailing campaign has proven, Bush’s trepidations were well founded. While Donald Trump and Ted Cruz have risen to dominate the polls, Bush has lagged far behind, unable to connect with a party that’s become reflexively hostile to signature programs he supports, like immigration reform and Common Core in education.

Bush has been floundering for so many months, it’s easy to lose sight of how odd this situation is—and of the profound truth it speaks about the state of the Republican Party. It’s easy to forget that Bush entered the race as the expected front-runner who quickly raised an intimidating war chest in a “shock and awe” attempt to ward off challengers. Moreover, members of the Bush family had been powerful figures in the GOP for decades—and, as befits a conservative party, Republicans have tended to be loyal to a few stalwart figures and families. Over the course of the last 70 years, only Richard Nixon comes anywhere close to being as much of a Republican fixture as the Bushes. From 1952 to 1972, Nixon was on the Republican ticket five times, winning four elections. From 1980 to 2004, a Bush was on the Republican ticket six times, winning five elections. In fact, the GOP has not won the White House without either Nixon or a Bush on the ticket since 1928.

Yet the family that has been a pillar of the party for decades now finds itself headed by a scion, poor Jeb, who came in sixth in Iowa with less than 3 percent of the vote. This broke pretty sharply with family precedent: George W. Bush won the Iowa caucuses in 2000 with 41 percent of the vote. For that matter, the patriarch George H.W. Bush beat Ronald Reagan in Iowa in 1980 before ending up in the number-two slot on that year’s Republican ticket.

Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary will likely decide the fate of not just Jeb Bush, but perhaps the entire Bush dynasty. It may also render a final verdict on the style of Republican fusion politics that the family has long represented. Currently clustered among the second-tier candidates, Jeb could conceivably rally his supporters, vault past his former protégé Marco Rubio to make a decent showing in second place, and regain his status as the establishment candidate. That would put him in a position to head to the next primary in South Carolina—where his brother George W. is slated to campaign for him—and compete with the national front-runners Donald Trump and Senator Ted Cruz in a potential three-way race.

Of course, the fact that Bush’s best-case scenario involves a series of far-fetched hypotheticals is a good indication of how dire his situation has become. If he fares poorly in New Hampshire, and especially if Rubio has a good night, even family loyalists who have stuck with the Bushes for decades will have to move on. “There is an increasing sense that Jeb Bush is running out of time to demonstrate strength,” reports Alex Isenstadt at Politico.

At this time of crisis, it’s worth taking stock of what the Bush brand of politics has represented. The family has never had a fixed reputation. Its political longevity has owed much to a chameleon-like ability to take on the coloration of different factions of the party. The Republicans combine East Coast patricians with Sunbelt entrepreneurs and evangelical Christians. With their shifting identities, the Bushes were able to play up these various roles. George H.W. Bush was both a Maine aristocrat and a Texas oilman, his eldest son George a Sunbelt capitalist and a born-again Christian. Jeb has similarly straddled the moderate-conservative divide, originally running for Florida governor as a hard-right candidate (and losing), but moderating (and subsequently winning twice) by emphasizing his outreach to Hispanics.

The Bushes haven’t had a consistent ideology so much as a recurring sales pitch: They always promise to give conservatism a human face, to be true to core right-wing principles but soften them with a dose of noblesse oblige. In essence, all the Bushes have peddled an ideological fusion that can cement the right wing and center of the Republican coalition. Hence George H.W. Bush both ran in 1988 as Reagan’s successor and promised a “kinder, gentler” America, while George W. Bush campaigned on “compassionate conservatism.” Jeb Bush’s commitment to immigration and education reform are his version of compassionate conservatism—but in today’s Republican landscape, they’ve made him toxic to the party’s xenophobes and hard-right purists.

The problem goes deeper than Jeb Bush’s “please clap” moments of embarrassment on the trail, or even the tarnish that George W. Bush’s disastrous presidency left on the family name. The GOP is so fragmented that the Bush style of Republican fusion politics can no longer unify. Beyond that, the hard right of the party no longer trusts the Bushes of the world, now seen as RINOs (Republicans In Name Only) who have consistently betrayed core conservative principles. To the party’s most fevered conservatives, especially in the Tea Party, George W. Bush is synonymous with budget deficits and the bank bailouts of late 2008 as much as with the failures in Iraq. The party now has large factions—Trump’s alienated xenophobes and Ted Cruz’s RINO-hating hard-right followers—for whom the Bush name is anathema. The Bush flag that once could rally different factions of the Republican party together is now itself divisive.

Over the last week, some political analysts, notably Franklin Foer, have argued that it’s too early to write off Jeb Bush’s chances. Writing at Slate, Foer observed that “seeing Bush press his case on the trail in New Hampshire, I was stunned by how he seemed high-energy, forceful, and confident.” With Rubio seemingly wounded by a much-derided debate performance on Saturday, when he couldn’t move beyond his canned soundbites, Bush might yet be the most plausible candidate the establishment has in the coming battle with Trump and Cruz.

If Bush were to garner some momentum in New Hampshire, he could continue on to South Carolina and stay in the race till he’s one of two or three alternatives; thanks in part to the family network, Bush’s campaign and its allied SuperPACs still have well over $60 million cash-in-hand. But the more likely outcome is that Tuesday’s primary will be end of the road—and the last stand for the Bush style of Republican fusion politics.