Like all head-to-head match-ups in modern politics, the Democratic primary race between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders has degenerated into an insufferable Twitter feud over who has the greater claim to ideological purity.

Lobbing familiar attacks over familiar differences is what candidates do before elections. But at this stage of the campaign it also serves to deepen enmity between party factions, without the added benefit of bringing any new information to bear.

That’s why it makes Democrats uncomfortable, and why Republicans can barely contain their enthusiasm.

Unlike most political spats, though, this one turned out to be at least minimally instructive, because it underscored a legitimate strategic concern many liberals have about Sanders and his allies. It’s also newsworthy coming on the eve of Thursday’s Clinton-Sanders debate, because it promises to bring the question of Sanders’s electability to the forefront.

The spat began two days ago, when Sanders said he thinks Clinton’s only a progressive “some days.” Clinton and her allies leapt to her defense, which in turn prompted Sanders to run through a litany of her heresies.

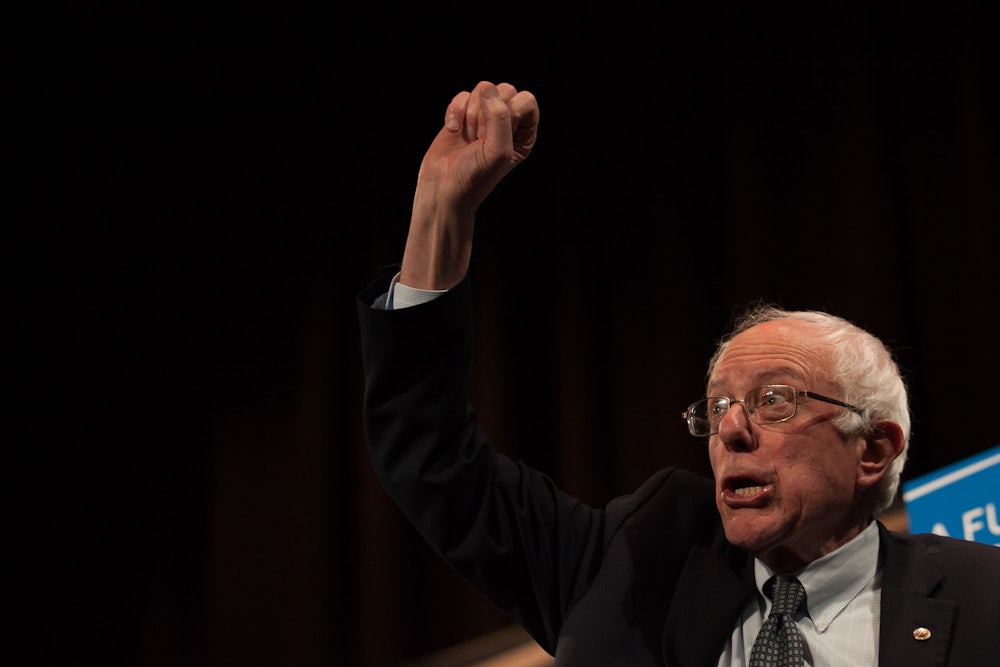

Here’s how he summed up his basic argument.

You can be a moderate. You can be a progressive. But you cannot be a moderate and a progressive.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) February 3, 2016

One of the questions at the heart of the fight between Clinton and Sanders is whether Sanders’s promise to lead a political revolution that brings the United States closer to social democracy is credible or fantastic. The argument frequently pits cynics and pragmatists, who see Barack Obama’s high-minded-candidacy-turned-difficult-presidency as an object lesson in the unloveliness of governing, against idealists and counterfactualists, who say Obama never attempted to turn the promise of his campaign into progressive action.

Even if you side with Team Sanders on this question, the insight that gave rise to that tweet (that pitting progressives against moderates is an effective tactic in a two-person Democratic primary) is incompatible with the goal of uniting the existing Democratic base with the unattached voters and Republicans of the white working class. It may even be incompatible with building a majority coalition in a general election.

The list of reasons to worry that Sanders is unelectable is unusually long. To paraphrase Vox’s David Roberts: Sanders would be far and away the oldest president to take office; he has self-identified as a socialist for most of his career, undeterred by the media’s inability to distinguish between social democrats (what he is) and Leninists (what Republicans will say he is); he supports a higher tax on middle-class labor, which is politically and substantively the worst way to finance a welfare state expansion.

On top of all that, he is unabashed about his disinterest in party coalition building. He’s happy to represent one wing of it, but not inclusively enough to pick up endorsements from influential party actors. This is all exacerbated by the fact that he’s spent his congressional career as an independent who caucuses with Democrats, and has never plied his popularity into helping Democratic colleagues get elected. This increases the likelihood that down-ballot Democrats would run away from him in a tough race, rather than rally to unite the party.

But you can set all that aside, too, and just consider the ramifications of Sanders’s defeating Clinton by boxing her out of the progressive movement, and using the term “moderate” as an epithet to describe deviations from his agenda.

For the better part of a decade, liberals have gazed upon conservatives with perverse glee as they’ve limited their ranks to an ever shrinking number of True Scotsmen. Their increasingly stringent criterion contributed to the failure of the GOP’s 2012 presidential nominee, Mitt Romney, who at one point had to atone for perceived heterodoxies by describing himself as “severely conservative.”

Ideologues, at least, comprise a very large (perhaps the single largest) faction of the Republican Party base. The same is not true of ideological progressives in the Democratic Party. Most progressives are Democrats, but most Democrats aren’t progressive. There will be no Sanders revolution without moderates, and moderates are unlikely to join a revolution organized by someone who stigmatizes moderation.

The irony here is that this is one of the main reasons liberals of all stripes hope that Ted Cruz (if not Donald Trump) wins the Republican nomination. Cruz’s critics in both parties compare him to Barry Goldwater, who lost 44 states to Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Cruz is resolute in his opposition to ideological compromise. When he announced his candidacy almost a year ago, he framed it explicitly as a campaign of, by and for “courageous conservatives [to] come together to reclaim the promise of America.” Cruz’s vulnerability in the general election stems from this factional identity—which, again, represents a larger faction than the one Sanders leads.

If Sanders were to win the Democratic nomination, his best, and perhaps only, chance to win the presidency would be in a general election campaign against Cruz. Somebody would have to win! For those with a very high risk tolerance, there’s never been a better time for a Sanders candidacy. But to pull it off—to make up for the fact that there are more ideological conservatives than progressives in the country—he would have to reconstitute the Democratic base, including Clinton supporters and other nefarious moderates. That might happen. A modern-day Goldwater against a modern-day George McGovern (who lost 49 states to Richard Nixon in 1972) would be a fascinating race to watch. But when Goldwater ran, the conservative movement was in its infancy and when McGovern ran, he never called himself a socialist.

Which is to say that even against Cruz, Sanders would represent an enormous gamble. A week ago I argued that Clinton and her surrogates had failed to make a persuasive case that Sanders stands to lose the presidency, leaving open the question of whether the gamble was worthwhile. That’s still true—in part because writing Sanders off would make reuniting the party more difficult, and in part because the Republican primary is rapidly neutralizing many of Sanders’s weaknesses. It’s furthermore true that if Sanders and Clinton are both more likely than not to win the presidency against a Republican, the argument for nominating Sanders becomes very strong. But as the race drags on, it’s getting harder and harder to grant that assumption—even if Clinton says nothing about it on the debate stage Thursday night.