This summer private madness briefly managed to push aside the wars, riots, and strikes that bedevil us. Pictures and stories cut a swath through the front pages of the newspapers, showing and telling a horrified nation that merely unfortunate or even exemplary men can become in a flash murderers, striking out of nowhere at anyone for reasons that never quite measure up to what they presume to explain. We learned that a “bewildered” Richard Speck, pictured looking just that, was declared by his lawyer not guilty of recently strangling and stabbing eight nurses to death in Chicago. We learned also that Charles Whitman, initially described as a model citizen and student, had the day before gone wild on the University of Texas campus, shooting and killing in all directions from the top of an observation tower, and in the end establishing something of a record for himself in the annals of what might be called American amok.

A few days after that, an 18-year-old school dropout told Texas police about the murders of two schoolboys and a schoolgirl he said his 20-year-old companion had shot and strangled. All over the world, those who needed additional evidence that America is a violent, murderous nation had it; and those who did not need it but wanted it for their own purposes also had it. The extent to which political commentators use events—of almost any character or incidence—to lend weight to one or another ideological persuasion perhaps goes unnoticed until the theories suddenly emerge, apparently ready-made and waiting for their chance. We were once again proven a savage, uncontrollable, unpredictable, gun-ridden and murderous people, with our pilots showering upon Asians the same brutal iron a Texan youth blasted down on his classmates in Austin.

Another category of observers heard from were those whose interests center not on nations but individuals. We learned that the message on Richard Speck’s tattooed arm—“born to raise hell”—showed the long standing and so to speak ingrained character of his violence. (I suppose thousands of men are now wondering what their tattoos forebode.) The man was described as a drifter, though a cunning psychopathic one who could successfully calm and persuade a room full of girls to comply with his wishes. A number of outraged people see the kind of justice our Supreme Court has now demanded as threatening that the murdered nurses (and the rest of us) go unavenged.

We had no reason to worry about having Charles Whitman’s head, but we were particularly anxious about what had gone on inside it. If Speck was the obvious (and reassuring) marginal man, Whitman at first seemed little more than the good American everyman, as we quickly found out. His credentials were imposing: a former Eagle Scout, a former Marine, a Scoutmaster, a good student, the handsome and eminently likable husband of an attractive woman. What else could we do but somehow find him secretly but decisively flawed?

In the effort no one was spared—members of the family, friends and experts, both willing and reluctant. Within hours of the tragedy Whitman’s father stood before the hungry, prying and poking devices of men who wanted to capture his looks and get him to speak his story. What did he know? How could he account for it all? Since the police had armed the interviewers with a précis of Whitman’s last, disordered notes protesting father-hate, it seemed only appropriate to rush to his father, confront him with the facts and ask him all about the family’s bad blood—particularly when the two women closest to the “child” were slain, along with another dozen people aimed at from a college building, and more than likely to be age-mates, class-mates, and thus contemporary competitors. If Whitman had ever feared asking his father anything, he died making sure others would have the chance he missed.

Meanwhile there was an autopsy and a discovery, both of which provided information enough to keep everybody curious rather than fatalistically resigned. A small tumor was found near the brainstem, and for a while neurologists all over the country were asked whether wildly multiplying cells could produce wild and unintended behavior. Slowly that possibility diminished. The growth was far away from the brain’s “thinking area,” and it turned out to be slow-growing and benign. In any event, what of those thousands whose nervous systems have been riddled with cancer? Every day they live and die among us, their suffering kept to themselves or shared only with sympathetic loved ones. The pathologist appeared to take that fact into consideration when he made his diagnosis: “an anti-social psychopath.” He added that “they are the worst kind,” and of course by definition he was right.

For a fleeting second there was the specter of drugs; a number of dexedrines were found in Whitman’s pockets. Might he have been excited and driven mad by pills? A less likely or compelling answer from the start, its worth soon faded. A sample of the dead man’s blood revealed not a trace of that or any other drug. Naturally, the same logic that had to be applied to the first guess would apply to the second: even more people work themselves up with dexedrine than fall sick to brain tumors, yet Whitman’s deed was unparalleled in its outcome, and its purpose had only a handful of recorded precedents in our recent history.

From the beginning the psychiatrists seemed the best if not the only hope; moreover, there was information—quickly made public—to support the conviction that underneath it all Whitman was already disturbed months earlier, and in the long run a product of a home whose peculiar troubles in some fashion would produce a sick mind if not a violently mad one. He had consulted a psychiatrist, in the South and West (except for California) not something to be taken for granted. Furthermore, his parents had just been separated, with the mother recently arrived in Texas to be near her son. In interviews with reporters the father called himself a “fanatic about guns”; they were said to hang in every room of his home in Florida. If the father was quickly found to be odd or “fanatic,” he was sure his son was a “sick boy.” Certainly he was “not the boy I loved and who loved his father.” Yes, he had been a strict father, but he had been raised an orphan and in poverty. Indeed, the more he told of himself the more typical (even archetypical) his life became. He had fought his way up with little education and through hard, muscular work to a position of money and respect. In the home he was an admitted bully, but a loyal, loving and generous one—the kind we all know, from top to bottom. To his neighbors he was the head of a stable, and by no means eccentric, family. Still, in Florida the father said his son was ill, though nobody knew what made him that ill.

In Texas a psychiatrist might be able to tell. I do not know why the officials in the university infirmary decided to break the utter confidentiality that must protect medical records. No one can deny an eager press and an anxious public the information they have a right to learn. A summary statement could have been issued, and certainly the doctor interviewed; but for a patient’s entire psychiatric record to have been instantly made available for no explicit medical reason seems to me at least a panicky reaction to a stressful situation. In any event the report had one distinct surprise to it. There was hostility; there was a history of family tension; there was a problem with study; but amid all that rather common clinical information there was one “vivid reference” made by the patient which the doctor quotes directly. He thought about “going up on the tower with a deer rifle and start shooting people.”

There it is, the deed predicted by the patient and the prediction written down by the doctor. Might it all have been prevented? Yet, as the psychiatrist left off reading his notes to comment on them and put them in the context of his daily work—and the experience of other psychiatrists—what seemed like the substance of welcome reason rapidly turned into the essence of bewildering ambiguity. It seems that many students bring a variety of suicidal and even homicidal fantasies to college psychiatrists, and in the University of Texas those fantasies often center on or involve the tower. To Charles Whitman’s psychiatrist—his, only by virtue of one visit—the patient’s story was coherent, unalarming, not exceptionally remarkable, but definitely an indication that help was needed, as with many others. Come back next week the student was told. I would imagine that most psychiatrists read of their colleague’s sudden predicament both nervously and sympathetically—as well they should. There is every reason to believe Whitman presented himself to the doctor as described: sane and possessed of rather prosaic difficulties that were destined to be transient.

We were left, then, with nothing substantial to “explain” a terrible crime, the obvious rampage of a madman. With each of his friends, acquaintances or teachers questioned, Whitman became steadily more ordinary. True, there were signs that he was on occasion tense; there were signs that he was almost too good; there were signs that he might have had something troublesome “going on” inside him; there was meager hearsay of occasional moodiness or mild, commonplace wrongdoing, such as gambling and even, in 1961, poaching. What it all ironically confirmed was that Charles Whitman was a fallible human being.

What is to be said—and done? Two men in rapid succession have once again reminded us of two enormously vexing problems that face, among others, any psychiatrist willing to look even a short distance outside his office. For one thing, we know much more about the way people think and dream than we know about their actions—about what they do or will do. For another, we face terribly complicated issues when we try to go from an individual’s illness to the various disorders that plague the masses of individuals we call a society or a nation.

We now can rummage over the lives of Richard Speck and Charles Whitman and raise our eyebrows knowingly over this and that detail, but to little avail. There are fiercely suspicious and sullen people whose minds are commonly worked up by hate and rage, whose thoughts in a second can be determined insane, whose parents may or may not have exceeded Speck’s or Whitman’s in roughness, toughness or worse—yet by the thousands they walk the streets a danger to no one but themselves. We simply do not know right now what specifically makes for the way people choose to act or find themselves acting, for the good or the bad. We can throw psychiatric labels around here and there. We can connect crimes to complexes and trace the gifted man’s productions all the way back to his mother’s womb. In doing so we only appease our own craving for answers and explanations. For every quiet, apparently harmless individual who becomes a criminal are there not dozens of manifestly angry and even crazy people who not only commit no crimes, but live extremely useful lives? Do not many so-called “ordinary” people share whatever pattern we find in a gifted person’s personality? These are yet riddles, not ones to shame any profession, but not ones to go unacknowledged, or be buried in a display of wordy and dogmatic psychiatric interpretations.

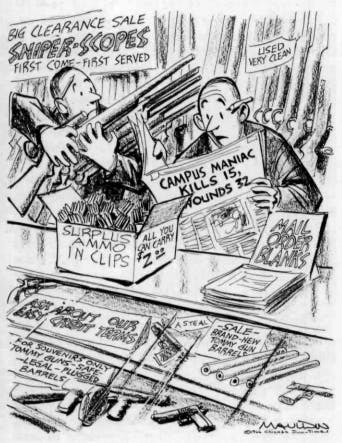

Equally

puzzling is the matter of what to recommend for a society startled by these

recent atrocities and presumably anxious to prevent their recurrence. As we

were in 1963 after President Kennedy was shot, we are again reminded how

readily guns can be obtained, not just rifles for hunting, but pistols and

automatic guns for human slaughter. The figures are appalling: Americans are

killed by fatal shootings at the rate of 17,000 a year, or nearly 50 a day. In

this century alone over 750,000 of our citizens have died from gun wounds “at

home,” as against a total of about 530,000 killed in all of our wars,

from the Revolutionary War to the present one in Vietnam. Nevertheless, Senator

Dodd’s fight to place even modest controls on the sales of weaponry has failed.

There is a powerful rifle lobby that watches our legislators from impressive

headquarters in Washington, and it is more than a match for any support Senator

Dodd may gain from the general (unorganized) public.

An Oswald or a Whitman calls attention to the millions of guns about, but only temporarily. People say it is dreadful, what has happened; then they ask whether a law restricting access to guns might have prevented the tragedy. The answer is that of course a determined murderer can get around any bill Congress is even remotely apt to pass and find his weapon. That is not the issue. Every psychiatrist has treated patients who were thankful that guns were not around at one or another time in their lives. Temper tantrums, fits, seizures, hysterical episodes all make the presence of guns an additional and possibly mortal danger. In this country today children can obtain guns by mail-order. I have treated delinquents who have grown up with them, not toy guns but real ones. We cannot prevent insanity in adults or violent and delinquent urges in many children by curbing guns, but we can certainly make the translation of crazy or vicious impulses into pulled triggers less likely and less possible. It is as simple as that, though many politicians refuse out of fear to let it be as simple as that.

There is, finally, the need we feel to make larger sense of individual behavior. Curiously enough, it is easier to deal with a mass murderer such as Whitman than with the concentration camps and battlefields this century has witnessed. We can call one man a lunatic (for what he has done, if not for what doctors can discover in him). That is, we can understand why he may have felt violent (and violated) even if we still do not comprehend why those feelings prompted in him the particular action he took. In contrast, what can we say about those many thousands who a few years ago killed millions in gas ovens or through bombing? The further we get from a particular person’s words or deeds, the more haunting and nightmarish is the whole business of man’s continuing murder of his fellow man. We say Hitler was an exception, a maniac become dictator. Yet, historians, political scientists and psychiatrists will discuss and argue the relationship between Hitler and his times, Hitler and Germany, Hitler and Wall Street or Hitler and the Communists until the end of time without providing what really cannot be provided: a tidy statement that demonstrates how countless people—large segments of whole nations—came to be murdered by the ordinary citizens of a supposedly civilized continent. Accidents, misfortunes, the crafty genius of individuals, complicated historical and political forces combine as “factors” to make any explanation of wars and institutionalized murder incredibly harder than the task facing us with even so puzzling a phenomenon as Charles Whitman.

On the very day Whitman killed 16, about the same number of Klansmen denied before a federal court in Mississippi that they killed one Negro man. If they are guilty, how do we explain their actions, their minds? What do we say about the mind of a man who wants to be governor of California, and is said to have suggested that North Vietnam be “turned into a parking lot”? How do we analyze the thinking of inscrutable leaders who would sacrifice a country’s entire generation to forced labor, prisons and hunger in the name of an abstraction like “dialectical materialism,” an ideology whose meaning and purposes cannot really be debated in such countries save by a very few? While “primitive” people have given something like amok a cultural form (among the Malay, Iban and Moslem groups of Borneo and elsewhere) mighty and “civilized” nations threaten to destroy everyone alive on this planet. The mind shudders before the prospect of looking at it all, the awful carnage of which man is capable. We turn away in disbelief, or we use every device to justify the unjustifiable. For a second the Whitmans of this world catch us by surprise and make us wonder— but not for much longer than that second, and not to any effect.