Like many people, Juan Thompson had a father who was frequently drunk, occasionally violent, and clearly ill-prepared to set his own childish impulses aside in the interest of raising a kid. As a lot of children before him have found, drug-addicted parents can be narcissistic and rarely award the comforts middle-class families are supposed to provide in their ideal and/or fictional state: material support, school tuition, a sense of propriety that excludes bringing your kid’s prudish girlfriend on a tour of a strip club.

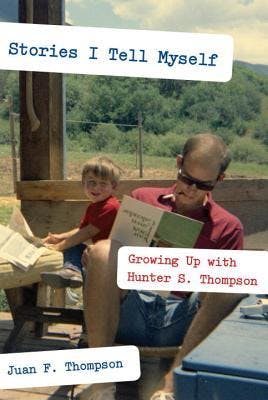

And as with a lot of kids—particularly those who decide to write books dedicated to their relationships with their parents—Thompson spent the early years of his life despising his father for all of those unfatherly quirks before ultimately, as he approached middle age, forgiving him. That the dad in question was Hunter S. Thompson gives the junior Thompson a built-in audience and some wild source material, but Stories I Tell Myself, out this month, is at its core a composite sketch of memoir’s most fashionable sub-genres: celebrity, drug addiction, and familial strife.

Juan Thompson has some company in his excavation of his relationship with his father, the extremely famous dead male writer. Since 2000, the daughters of novelists Bernard Malamud and William Styron, as well as Saul Bellow’s son, have written books about their notable parents. Inevitably a significant part of these books address what some might refer to as a poor work-life balance but what to children feels like neglect. When James Wood reviewed Bellow’s book, he infantilized the adult son’s anger, characterizing it as “a child’s complaint” about the fame that ostensibly stole his father away from him. When we talk about sub-par parents who also happen to make things we admire, there’s little room for ambiguity: Writerly dedication is too self-serving to wipe snotty noses or show up on graduation day. But that doesn’t exonerate them; it’s not as if they had to have children in the first place. Writers such as Virginia Woolf and Rebecca Solnit and Anna Holmes made what looks like, under the circumstances, the rational choice, judging themselves too unstable or solitary or simply too selfish to procreate.

Unlike many writers, though, Hunter’s celebrity is more cinematic than literary. None of the other writers I’ve mentioned were caricatured by two of their generation’s most recognizable actors during their lifetimes, and few harnessed their own dysfunctional tendencies so thoroughly in the service of their work. Thompson may have wanted to be a novelist, but his contributions to culture will be remembered as personality-driven first, with his political journalism trailing closely behind it. Thompson is a famous writer, sure, but he’s also an enduringly viral one: Even if you’ve never read his books, you may have come across the letter he wrote to the editor of the Vancouver Sun in which he describes his “healthy contempt for journalism as a profession,” or the response to Anthony’s Burgess’s failure to file for Rolling Stone where he calls the famously prolific author a lazy cocksucker. (“And you thought your editor was tough,” tweets the #amwriting Internet).

At the outset, Juan Thompson claims he wrote this memoir in order to combat that caricature of Hunter, the version of his father that foregrounds him as a bumbling, cross-eyed “wild man”; I guess if Hunter were my father I’d be frustrated, too, by the (nearly always male) Gonzo enthusiasts who haunt the internet, aping the grim staccato of Thompson’s reporting, placing “the good doctor” in the pantheon of macho, toxically-inclined dudes of note right next to Chuck Palahniuk. But Stories I Tell Myself ultimately doesn’t reveal much, save that Juan is a measured, nice, nerdy guy who grew up to work in IT. A good chunk of the book is dedicated to Juan’s struggle to understand the swashbuckling masculinity that Thompson embodied, both publicly and privately. And around the margins, female characters—most notably Hunter’s long-time (and apparently unpaid) assistant Deb—dedicate themselves to taking the edge off the writer’s manic tendencies, an angle that probably deserved a little more discussion than it was given in this book.

I mean, of course Hunter wasn’t a great father, and alcoholism is an ugly disease at the end of one’s life, and having to deal with celebrity parents in a certain era has a sort of sceney set-piece appeal to the average reader. Unlike most children whose parents go through a divorce, Juan took off and and played cabin boy on Jimmy Buffet’s boat for a few months. He dropped acid—in a mindful manner; this is the 1970s after all—with his mother, though he says his father would have “beaten the shit out of him” had he found out. He survived the awkwardness of dating women who had read Thompson’s work in depth. He and Hunter shared moments of intimacy cleaning guns together, right up until the end, when Juan unwittingly oiled and reassembled the Smith & Wesson his father used to shoot himself.

It took nine years for Juan Thompson to write this book. In interviews he’s described the process as “emotionally taxing” and “exhausting”; as with most books in the genre, the language of catharsis is integral to the process of its writing and probably extremely useful for the final marketing push. But when the five stages of grief could conceivably be performed in private, it’s worth asking what angles a child’s perspective should add to the profile of such a public figure, particularly when it’s someone who already produced so much autobiographical information himself. There’s about as much literature about Thompson the practicing writer, if you’re interested, as there is about Thompson the celebrity. As Juan himself points out, in Hunter’s later years his mental faculties scattered and rendered even a 1,000-word article something of a major feat. To keep paying the bills—and satisfying demand, one would assume—Thompson instead published collections of previous work and several volumes of his letters.

I’m sure it’s infuriating for those who knew him intimately that Hunter S. Thompson may be the kind of writer whose truly awful fans and imitators end up dictating his legacy, and that they’re so enamored with Hunter the cowboy, the gun enthusiast, the hedonist, that some take his work as proof that writing is a man’s pursuit. But when the question of whether parents—particularly female ones—are capable of brilliance without damaging their offspring has been the subject of intense debate, a retelling of Hunter S. Thomson’s domestic challenges comes off a little sour. Remove the last names and telling details from this book and it’s an addition to an already saturated genre; focus on the celebrity at the heart of it and it’s a recitation of what we already knew.