There is no marker at 87th Ave NW aside from a green street sign where the paved road turns to gravel. There is no billboard, no placard with an arrow directing a traveler to a place of interest. No crescent moon or other subtle indicator.

My car kicked up dust. In North Dakota unpaved roads are the norm as soon as you get out of town and off the main highway. Here, outside of Ross, population 100, the landscape appears as a prairie mosaic of farmland, pasture, and oilfield. Wheat, cattle, bobbing pumpjacks—and somewhere in all this, the site of the first mosque in America.

I read a map on my phone. It was August, and I had been in North Dakota for six months doing research on the oil boom. The first time someone told me about the mosque, I didn’t believe it. In North Dakota? How? But various sources agree with the claim, even if it comes with an asterisk. Other buildings in the United States may have been used as mosques before this one, but the first structure built specifically as a Muslim place of worship was a nondescript building in rural North Dakota.

In recent years the oil boom has remade the northwest corner of the state into a multicultural hub, one where I heard Spanish at home, Amharic at work, Bulgarian at the gym, and African-inflected French at church. In the early twentieth century the area would have been no less cosmopolitan: a polyglot countryside where the locals spoke Norwegian, German, Ukrainian—and Arabic. It was in this improbable setting that a group of Syrian homesteaders erected a building for worship that they called the “Jima,” a variation on an Arabic word meaning “assembly” or “gathering.”

By the 1870s the U.S. government had wrested control of the northern Dakota Territory from the indigenous population. In 1883 the Northern-Pacific railroad went fully operational. Homesteaders followed. In exchange for farming, a settler could receive 160 acres of fertile prairie. It was free land, a way to establish a stake in this country. Many who filed for homesteads in North Dakota came from abroad.

Those from abroad included immigrants from modern-day Lebanon, then a part of the Ottoman Empire known as Syria. Some came to escape what they described as the heavy-handed rule of the Turks. They called themselves Syrians, and they settled around the town of Ross, among other places. William Sherman’s book Prairie Peddlers reports that the first Muslim family to file for a homestead near Ross did so in 1902, with dozens more to follow. They farmed the land, “proved up”—meaning they satisfied government requirements needed to own the land, which took two years or more—and established an enclave of Arabic speakers with surnames such as Juma, Abdallah, and Omar.

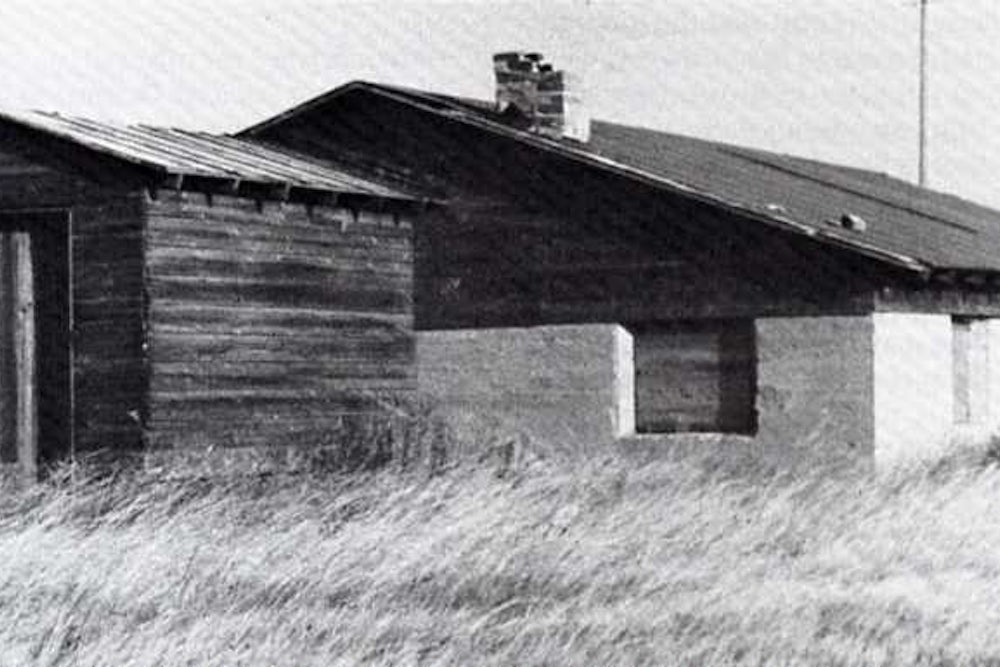

In

1929 they built a mosque.

A grainy photo reproduced in Sherman’s

book shows a low-slung rectangular structure built on a shallow

basement. It has a gabled roof and a stone chimney. The walls are made

of concrete, and a wooden anteroom

marks the entrance.

The building is modest

and unremarkable. Nothing about

the architecture suggests that it would be a place

of worship. It could easily

be a workshop or a stable.

I didn’t know

what to look for. The

original structure

was taken down in 1979 after it fell into

disrepair, the Muslim community in

Ross having shrunk over the course of the twentieth century as

people moved away or married into Christian families. A decade

ago a local family of Syrian descent raised money for a new building, a memorial to

the original. I drove half a mile down

the gravel road. Around me was the

familiar green of cropland and rolling yellow-brown of

pasture. Cattle grazed in a field

to the

east. And then, on a slightly

elevated plane to my

right, obscured at first by three

squat trees, was a square stone building, hardly

bigger than a storage shed,

with a bronze dome and four short spires—an unambiguous

echo of Islamic architecture.

I parked my car on the edge of the gravel road. A metal gate, its two halves loosely chained with a lock, marked an entrance, which was framed by a simple, attractive wrought-iron banner showing a crescent moon and a star. On the other side was a grassy lawn, well-maintained and more than an acre in size. I slipped through the gate to get a closer look.

The new mosque sits on the lawn’s north side. It has no ornamental details, nor does it have any windows to peer into. My eyes measured it at about fifteen feet on each side, and the exterior appeared to be splitface concrete blocks, an inexpensive and utilitarian choice. In the ground you can see evidence of the old building’s footprint, which was quite a bit larger than the current one.

The Muslim homesteaders who built the original mosque would have arrived at a sparsely populated prairie frontier, one with few amenities and little infrastructure. They plowed under the native grasses and planted wheat, rye, and oats. They raised sheep and cattle. They built farmhouses and barns. In the summer they worked in temperatures that topped 100 degrees, and during the winter they braved temperatures that reached 40 below. They endured hailstorms, grasshoppers, and drought. As one must in a harsh, isolated setting, they would have come to their neighbors’ aid in times of need, and likewise they would have received help in return.

In a way, these Syrian homesteaders, half a world away from their native villages near the Mediterranean, were like the yeoman farmers that Jefferson had idealized. They practiced the virtues of hard work and self-determination that Americans today still valorize. They also participated directly in our country’s first empire-building project, an effort to acquire and populate the territory that has become today’s United States—this effort aided, to be sure, by the dispossession and violent “pacification” of American Indians, some of whom were sequestered on a reservation a mere 30 miles from the mosque. These Muslim homesteaders are part of that legacy as well, a fact that binds them not only to our country’s glory but also its shame.

When they died they were buried in a cemetery on the grounds of the mosque. I walked across the lawn to look at the gravestones. A couple dozen plots, most of them grouped by family, make up the burial site. Some of the markers were showing the wear of decades. Behind the cemetery a pond flecked sunlight.

In 1939 a fieldworker with the Works Project Administration interviewed Mike Abdallah, one of the Syrian homesteaders whose family is buried in the cemetery. Abdallah immigrated to the U.S. in 1909. In 1915 he filed for a homestead near Ross. “In this country we get improvements for our tax money and we can think and say what we want,” he told the WPA interviewer, “while in the Old Country we could think what we wanted but we didn’t dare say it.”

Toward the end of my time in North Dakota I worked as a derrickhand on an oil rig. In early December we were servicing a well near Ross, no more than a few miles from the site of the mosque. At the end of the day I was driving the company pickup back to Williston, our home base. As we passed the turn-off to the mosque I mentioned it to my co-worker, a veteran roughneck with 15 years in the oilfield.

“You want to hear something amazing? The first mosque in America is right down that road there.” I told him about the Syrian homesteaders. It had been a month since the attack in Paris and just over a week since the shooting in San Bernadino. A few days earlier Donald Trump had called for a ban on letting foreign Muslims enter the U.S. Governors around the country, including the governor of North Dakota, had vowed to refuse Syrian refugees in their states.

“Somebody should blow that fucker up,” he said.