Where do phobias

come from? And how do they become political? In a recent New York Times article, Amanda Hess addresses these questions in an

investigation of phobia’s rise as a sociopolitical register. Titled “How ‘-Phobic’ Became a Weapon in the

Identity Wars,” the

essay shows that the “modern ‘-phobia’ boom” can be traced back to New York

psychologist and gay rights activist George Weinberg, who coined the term “homophobia”

in his 1972 book Society

and the Healthy Homosexual.

“‘Homophobia’ was a hit,” Hess explains. It became the go-to “descriptor for

the intolerant” and a rallying point for gay liberation worldwide. Since then,

phobia has fully infiltrated activist lingo. “Islamophobia,” “xenophobia,” “transphobia”—each fulfills a hallowed role for a corresponding social movement, organizing

an array of discriminatory acts into an all-purpose buzzword.

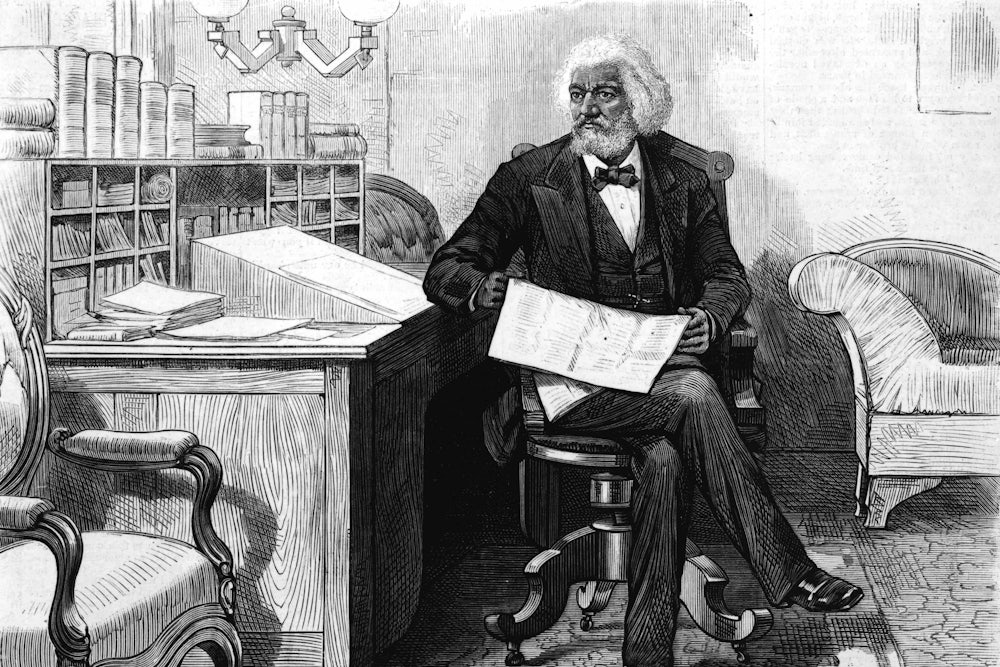

But if we want to understand the origins of this phenomenon, we have to look beyond the history of homophobia in the twentieth century. For more than two hundred years, Americans have been using the “phobia” suffix as a political weapon. In fact, the first progressives to recognize its rhetorical power were not gay rights activists but nineteenth-century abolitionists. Two terms became especially prominent: “colorphobia” and “Negrophobia.” Armed with these neologisms, abolitionists developed a vocabulary that not only contested the slave system, but also unearthed an emotional basis for slavery’s persistence. In their eyes, racial phobia was a malevolent force—one that threatened to tear the nation apart. It was not uncommon for pieces published in Frederick Douglass’s The North Star, William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, Charles Bennett Ray’s The Colored American, and Lydia and David Child’s National Anti-Slavery Standard to focus entirely on rooting out “cases” of “colorphobia” and “Negrophobia.” At the end of the Civil War, newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic had published hundreds of editorials tackling race prejudice in these terms.

By the late 1830s, colorphobia and Negrophobia had become central to national conversations about slavery and social life. Does this mean we have at last uncovered the origins of our many political phobias? Well, not exactly. It is precisely now, during a resurgence of the phobic imagination in political circles, that we should resist assuming a perfect correspondence between antebellum phobias and our own. Colorphobia and Negrophobia originated in a lexical relationship that has since faded from historical memory. The terms were, in fact, first imagined as analogies of a disease called hydrophobia, the predominant name for rabies until the late nineteenth century.

Transliterated

from the Greek word ὑδροφοβία (in the late fourteenth century, according to the

Online

Etymology Dictionary),

hydrophobia was the only major term in English to adopt phobia (φόβος)

as a suffix for hundreds of years. Hydrophobia persisted as a name for rabies

because it was believed that an intensifying fear of water was the first and

most recognizable form the disease took. Not until the influence of Benjamin

Rush did new phobias begin to garner interest. Remembered today for being the

“father of American psychiatry” and one of the signers of the Declaration of

Independence, Rush introduced an original taxonomy of phobias in 1786, in an

essay titled “On the Different Species of Phobia.” An amusing piece halfway between

entertainment and sincere speculation, the essay cites hydrophobia as

inspiration for fifteen other “species” ranging from Rat Phobia and Doctor

Phobia to Church Phobia and Rum Phobia. As colorphobia and Negrophobia became two

of the most commonly referenced phobias of the following century, they retained

this same analogy to rabies.

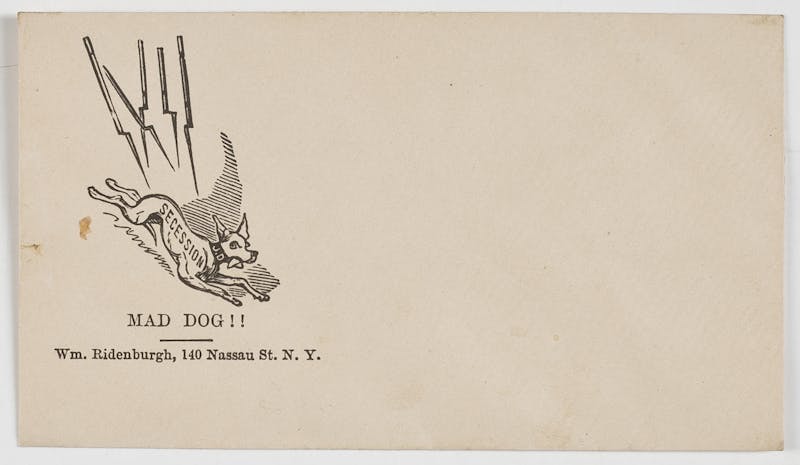

Hydrophobia was vital to framing the rhetorical fashion that followed. A writer for the black New York newspaper The Colored American put it this way in 1839: “The word [colorphobia] is first cousin to hydrophobia and so is the thing. It is a terrible insanity produced by the bite of slavery.” In short, hydrophobia imbued the charge of racial phobia in antislavery circles with a vivid picture of proslavery’s mentality. Consider, for instance, an impassioned piece published in Vermont’s The Voice of Freedom in 1839. Deciding that colorphobia had become a distinctly American feeling, the author cites the United States as the great “mad dog” at the root of the disease. The species “is peculiar to the land of liberty,” he writes, “where they all get bit by him, and the phobiac is indelible,” no more able to bear the sight of black persons than “a poor dog in the last stages of the rabies canis could bear the sound of Niagara falls.” Colorphobia was more than just a newly coined idea: It held in its etymology a riveting metaphor.

This was no monotone metaphor, either. The phobia in hydrophobia was not just about fear. It pictured American slavery as a vicious, inhuman, rampaging beast, surrendered to a furious insanity. An article titled “A New Kind of Phobia,” published in 1846, thus concludes its comparison of hydrophobia and Negrophobia by emphasizing their most damning resemblance: “Both are apt to bite and tear their species, being filled with a most unnatural hate against them.” Equally relevant to the abolitionist mind was hydrophobia’s contagious quality. Rabies was not yet known to be a virus, in the microbial sense; that development would come much later, with the birth of microbiology in the 1880s and 1890s. Yet the transmission of the disease was clearly passed on through animal-on-human and even human-on-human attacks. With this threat in mind, one writer lamented in 1853, after hearing reports that Canada was becoming unfriendly to black fugitives from the South: “Canadians have caught from us the contagion of negro-phobia.”

This is not to say the antislavery turn to phobia had nothing in common with activism in the twenty-first century. Hess isolates three tantalizing advantages to phobia’s contemporary usage: Phobia imitates medical discourse, to point out the neurotic and irrational hang-ups that often underlie prejudice; it stages a provocation—a “trollish imputation” that bigotry is only a veneer for the “politically scared” (here we have something like the childish taunt, “What are you, chicken?”); and, for less established movements, mimicking the familiar suffix also lends instantaneous credibility. Hess cites fatphobia as one example: “A copycat neologism (like ‘fatphobic’) automatically conjures a comparison between a struggling cause (like fat acceptance) and the overwhelmingly successful gay rights movement.”

Being the guinea pigs in the early years of phobia’s ascendancy, colorphobia and Negrophobia established, rather than benefitted from, the third advantage. However, the first two attractive qualities Hess mentions had important antebellum counterparts. By subjecting antebellum whites to clinical scrutiny, the rhetoric of racial phobia offered a sharp counterpoint to scientific racism, as practiced by the likes of Samuel George Morton and Samuel A. Cartwright. It offered a way of reading whiteness itself as pathological. It wasn’t long before colorphobia and Negrophobia evolved into barbed epithets too. The terms acquired a satirical edge, used to shame racist acts, persons, and policies in the North and South alike.

Nevertheless, the more colorphobia and Negrophobia caught on, the more disappointing they began to appear. By the late 1840s and 1850s, a handful of abolitionists began questioning whether colorphobia was, in fact, becoming more of an excuse than a polemical tool. An 1848 piece in Douglass’s The North Star, written by his printer John Dick, conveyed those doubts candidly. Titled “Colorphobia—Who Are Its Victims?,” the piece observes, “It is difficult to know whether those who are afflicted with this disorder, are most to be pitied or despised.” While Dick admits their “sufferings” and “torments” are obvious, he stipulates that “when we consider that this is the result of ignorance—ignorance of the most deplorable description, which they might, if they had chosen, have prevented—our pity becomes, in some degree, modified by an admixture of contempt.” Motivating the article is a sense that colorphobia’s focus on irrational fear was giving slaveholders and their political allies the benefit of the doubt, implying they could not perhaps help themselves.

A greater number of abolitionists began to see that phobia’s rhetoric was getting in the way of a crucial point. If Southern slaveholding had anything to do with fear, it wasn’t so much a fear of people of color as it was a fear that white supremacy might be exposed, challenged, and demolished. Thus motivated, a writer for Charles Swift’s Yarmouth Register in 1862 proposed a new name for the disease. Discontented with Negrophobia’s connotations, the author explains: “After some thought, I have concluded that their disease must be Negro-equality-phobia.”

As phobia came into its own as a default expression, it yielded increasing ambivalence among abolitionists. Skepticism over phobia’s connotations have returned periodically ever since. As Hess notes, the Associated Press struck political phobias from its stylebook in 2012, arguing that the allusion to mental illness is misleading. Hess herself takes a position not far from the abolitionists above. “‘Phobia’ is now so embedded in our language that it’s easy to forget that it is a metaphor comparing bigots to the mentally ill.” The consequence is that from a certain angle it begins to look more like justification than critique.

Yet the greatest deficiency, now buried in archival obscurity, is that the metaphor that once inspired phobia’s role in political rhetoric, its raison d’être, has since vanished. Without it, the suffix simply would not have taken off. As for a date when the hydrophobic allusion began to drop out of American culture, the best candidate may be the triumph of Pasteur’s rabies vaccine in 1885. Disseminated shortly after in the U.S. as “An Inoculation for Hydrophobia,” it seems nevertheless to have sounded the death knell for that very word. The term’s popularity experienced a sharp decline; “rabies” started to become standard. The lexical kinship between phobia and canine madness began slowly to dissolve. To put it succinctly, phobia lost its bite.

Bigotry does, of course, have a lot to do with fear—no matter its ideological motivations. George Weinberg insisted on this point in an interview with the Advocate in 2012, defending homophobia’s use after the AP ban. “It encapsulates a whole point of view and of feeling,” he explained. “It was a hard-won word, as you can imagine. It even brought me some death threats. Is homophobia always based on fear? I thought so and still think so. Maybe envy in some cases.” In either case, Weinberg argued, it remains “a psychological question.” Important as this reminder is, “phobia” was never only about fear—and it didn’t become a political epithet in the twentieth century. Understanding why the suffix feels “off” in its modern incarnations means recognizing that its potent symbolism has since dissipated.

Douglass and his contemporaries help us clarify a more incisive critique of phobia’s modern uses. The takeaway is not that metaphors are intrinsically bad or deceitful. Metaphors enlighten us precisely because they upset our fine distinctions. By connecting unlike things, they remind us that nothing in life is so perfect as a word, stripped of its ambiguities. Phobia’s flaw lies not in the messiness of figurative language, then, but rather in the smooth sedimentation of a singular idea. Only when we sacrifice the hard work of comparison for rhetorical comfort—the ease of a readymade epithet—do metaphors lose their efficacy. It is then we find ourselves the inheritors of a tradition emptied of its purpose, caught in a false struggle between pragmatic familiarity and naked precision. Instead, we might proceed by charting new parallels.