When it comes to democracy, the kids aren’t all right.

Research recently presented by Roberto Foa and Yascha Mounk shows growing disillusionment with democracy—not just with politics or campaigns, but with democracy itself.

This growth is worldwide, but it is especially strong among young Americans. Fewer than 30 percent of Americans born since 1980 say that living in a democracy is essential. For those born since 1970, more than one in five describe our democratic system as “bad or very bad.” That’s almost twice is the rate for people born between 1950 and 1970.

I have written on democracy and democratic politics for decades, and I have been watching these trends over much of that time. In 2008, people like me breathed a sigh of relief as young people came out in droves to vote. It was great to see them participating in our political system.

But in 2014, voting rates for young people hit record lows.

Will things turn back around in 2016?

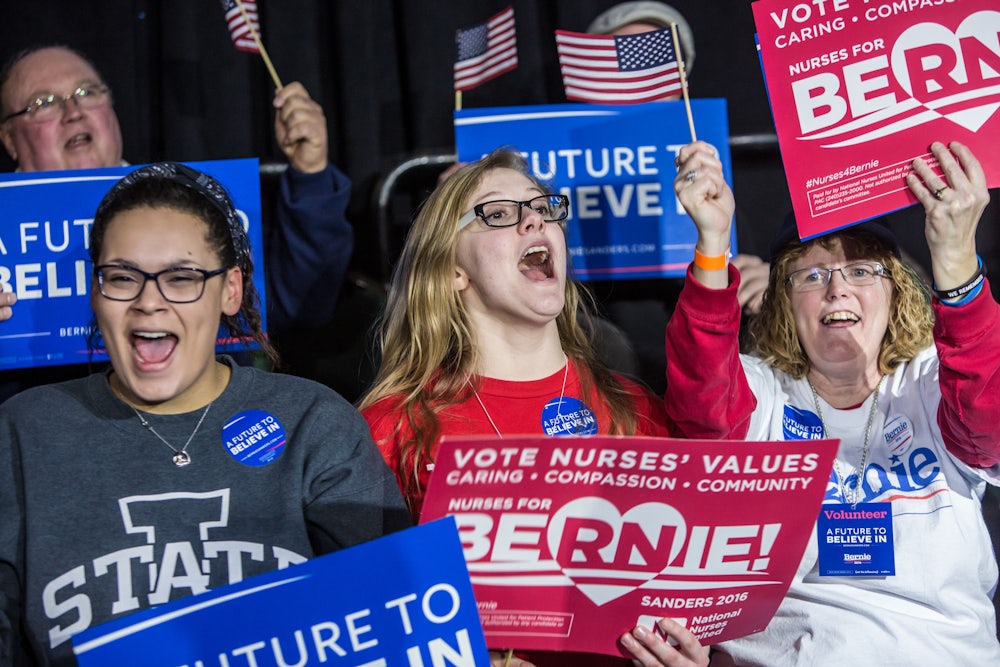

Those of us concerned about young people’s attachment to democracy are encouraged to see strong youth engagement in the “outsider” campaigns of Donald Trump and especially Bernie Sanders. But there is still cause for concern.

Young people checking out of politics altogether as well as those attracted to Sanders’ campaign are driven by their dissatisfaction with the status quo. In both cases, I believe their dissatisfaction is well-founded.

How did we get here?

There are good reasons why young people don’t respect American democracy.

The 112th Congress passed less legislation than any since 1947, and the 113th was second-worst.

The current 114th session is doing only slightly better. Children coming into adulthood have never seen democracy as anything but a system where politicians snipe at each other without end and without result.

Elections are supposed to be the way we change this. Yet while approval ratings for Congress hover around 10 percent, 19 out of every 20 members were reelected in 2014. Despite the people’s overwhelming disapproval, elections are not leading to change.

There are two main reasons for this, and neither gives young people much reason for confidence.

Barriers to change

First, the price of a congressional campaign has risen dramatically, costing “on average twice as much as it did a quarter century ago.” The average was up to about $1.6 million in 2012. For any candidate who is not independently wealthy, these costs put a viable race out of reach. And of course, those with deep pockets are unlikely to back a challenger when they know prospects for success are that low.

More important, there is the matter of gerrymandering—state legislatures drawing district lines in order to render seats safe for U.S. representatives.

The term was coined early in the nineteenth century, so there is nothing new about this strategy. But the 2010 off-year election was a landslide for Republicans, giving them complete control of redistricting in almost half the states. As a result, Democrats were packed into as few districts as possible, while the Republicans were left to divvy up the rest of the state. Republicans were therefore able to win and keep more seats, but seats for both Democrats and Republicans became decidedly safer.

But government is not merely inefficient and unresponsive.

Elected officials themselves say that government is crooked, if not outright criminal. Senators Ted Cruz and Bernie Sanders both repeatedly say that Washington is corrupt.

During the Republican presidential debate in Boulder, Governor Chris Christie said:

The government has lied to you and they have stolen from you.

If this is how people in government describe government, why should anybody have any confidence in the political system that put them there?

Civic education: bad or inadequate

But it is not simply a matter of what they have learned from politicians, it is also what they have not learned as students. In short, many young Americans have not learned how to be politically engaged.

Beginning in the 1990s, many school districts turned to “service learning” as a replacement for traditional forms of civic education. Offering students the chance to help their neighborhoods through spring cleanups and food drives was seen as a way to instill community spirit.

And it worked. Millennials do indeed appear to be extremely generous and socially conscious. But service learning hasn’t promoted an interest in politics.

In fact, precisely because so many schools focus on service learning, many students have not learned how to connect underlying problems to politics: that is, through voting, organizing and petitioning. Acquiescing to students’ distaste for politics, schools offer students a deficient understanding of what it means to be a citizen, thus reinforcing and sanctioning their attitudes.

Not all by accident

Finally, Republicans have endeavored to exclude young people from the voting process. According to NYU’s Brennan Center, between 2010 and 2014, at least 22 states passed laws that make it harder to vote.

Some of these restrictions, including shortened voting hours and new ID requirements, target college students and other young people.

Young people tend to vote Democrat, so these laws have the apparent and almost certainly intended effect of keeping Republicans in office. Of course, some young people see these restrictions as a challenge—no one is going to keep them from voting—but for those who are already disconnected, the extra hassle is just one more reason to check out from the process altogether.

Through words and deeds, then, we have taught young citizens that politics is not their concern, and that democracy is fool’s gold. Unfortunately for all of us, they have learned the lesson.

What happens next?

The 2016 campaign so far suggests that young people may not be democracy’s lost generation.

In fact, their learned distaste for democracy, paradoxically perhaps, may account for the strong interest young partisans show in Donald Trump and especially Bernie Sanders. Among voters under 45, Sanders holds a more than two-to-one lead over Hillary Clinton.

Seeing rampant evidence of inefficiency and hearing charges of corruption, they look to outsiders to radically alter the status quo. Whether these candidates are successful or not, their young followers might end up disappointed at the amount of radical change they see. Nevertheless, part of the reason for the success of these candidates is their ability to tap into young people’s deep discontent with democracy as they know it.

It would help if more candidates tried to engage young people. Even better would be if they directly addressed their discontent. Young people need to hear politicians acknowledge that politics has let them down. They also need to hear from candidates how they plan to restore their faith in democracy.

But we cannot simply rely on charismatic individuals to help students awaken their political selves. We must rather undertake the hard work of restoring their faith in democratic politics. Most importantly, we must recommit to a robust civic curriculum.

In the words of Jefferson:

The qualifications for self-government in society are not innate. They are the result of habit and long training.

To help students prepare for their role as voters, we need to help them learn how to take part in politics. Only after we have fulfilled our responsibilities can we judge young people for having failed to live up to theirs.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.![]() Read the original article.

Read the original article.