Werner Herzog’s new film Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World is a sprawling exploration into the past, present, and future of the web. The documentary, which premiered this week at the Sundance Film Festival, is strategically divided into ten chapters, hitting on everything from the perils of web addiction to the potential risks and rewards of artificial intelligence. Like many of Herzog’s celebrated documents of life, Lo and Behold is at its best when its filmmaker is curious and inquisitive, hungry for answers about the labyrinthine technocratic age.

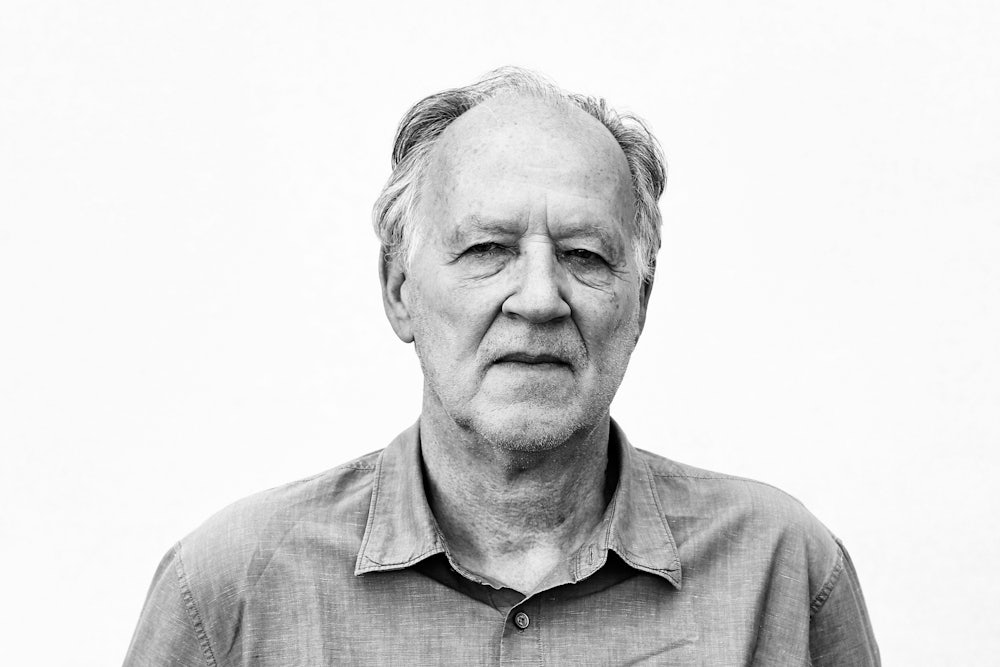

Sitting across from Herzog, with his towering presence and unmistakable accent, is as intimidating as you might imagine. In conversation, though, he is generous and forthright—ready to speak his mind when it came down to the fundamental matters of love, survival, and death.

Sam Fragoso: Do you enjoy festivals like this?

Werner Herzog: No, there’re too many of them, and too few good films. We have 4,000–5,000 festivals a year, but we only have three of four good films a year.

SF: What are the good films from last year?

WH: Act of Killing [a documentary Herzog executive-produced]

and some of my stuff.

SF: How big of a role does technology play in your life?

WH: In my personal life, it has a reduced presence. For cultural reasons, I do not use a cellphone, for example.

SF: What does that mean?

WH: It means that I do not want to be available all the time; I do not want to be dependent on information that I get through there. Sometimes there is shallow information that I need—Is there a traffic jam ahead of me? So, that’s fine. But, I’ll give you one example: I’ve been at the house of friends who have a teenaged daughter who sits at the dinner table and after five minutes puts her face down, and under the table, she’s texting, and throughout the next hour-and-a-half, she’s not there anymore. I mean physically, she’s present, and she’s texting.

SF: Does she

represent the future to you?

WH: No, it’s one side of what’s coming. That has already materialized. I do not want to have a meal with people who are tweeting at the same time; it’s as simple as that. The internet I do use, mostly email, and it’s a fine instrument.

SF: With the mass

consumption of technology, do you think we’re heading into a lonelier place?

WH: I think you are right, because it sounds like a paradox. The more tools of communication we have—it’s not only the internet and cellphone, it’s also television and radio, faxes used to be part of it. … But the more available and the more massively our tools of communication have expanded, in reverse proportion, we have become more solitary and lonesome. Not solitary, because when you are out in a snowstorm in Utah, and you’re snowed in and you have a cellphone on you, you’re not isolated anymore, because you speak to the state trooper, and they send a helicopter to rescue you. Which is very fine that we have that. But at the same time, on an existential level it’s a deep solitude, it’s somehow enshrouding us, and this century, because of that, will be the century of solitude.

SF: Do you

believe people would rather be alone than with other people?

WH: That’s one thing a renaissance of being unconnected and just in silence and alone may resurge: self-reading, deep reading, not just reading tweets, but ancient Greek drama, Tolstoy, a 850-page novel. And without that, we’ll never have a conceptual grasp of what the world is all about. And I have this dictum: Those who read gain the world, and those who are too much on the internet lose it.

SF: There’s a

chapter in the film that dives into when, not if, Earth will be damaged by a

sun flare. When your interview subject spoke so candidly about our fate, were

you as horrified as I was?

WH: If you are conceptually prepared for it and if you do the right thinking, then yes, you can easily cope with it.

SF: How have you

coped?

WH: In practical terms, everyone is talking about, Oh, it’s the end of cash money. Yes, in a way, [cash] disappears more and more. However, I advise you to have a stash of one- and five-dollar bills at home.

SF: Is that what

you have?

WH: I don’t have it at the moment, but it would be my advice, because at least you can buy a few gallons of gasoline at the pump, or you can buy a hamburger at the hamburger joint. They cannot give you change for a 100-dollar bill. For the immediate necessities, you better have a stash of drinking water, a flashlight, a few dollar bills.

SF: Would you

characterize yourself as optimistic?

WH: No, let’s not get into that.

SF: Fine, but…

WH: I would be a good outdoorsman. I could survive longer than the average man. I can make a fire, I would be a good hunter, I have traveled on foot, I could still survive a little bit longer than, let’s say, the average.

SF: Definitely longer than me.

WH: But you can’t drive your car, you’d have to walk and find some place where people live off the land. I think before we start talking about Carrington Joseph, we must realize you have just as much of a risk of Yosemite going up in a super volcano and plunging in a Dark Age.

SF: And this doesn’t worry

you?

WH: No. It’s a philosophical question. I’ll do you: How do you settle the question of your own death? You cannot be scared.

SF: Have you

always had this approach?

WH: I would say from a certain point in my life, I was not scared anymore.

SF: What point

was that?

WH: I can only give you a simple answer: That man who scares me has to be born first. And I’ve been shot various times, not just once. So what?

SF: You know you’re

the only filmmaker to make a movie on every continent?

WH: You shouldn’t say it loud. Because somebody is going to put me in the Guinness Book of World Records, and that would be my deepest embarrassment.

SF: A picture of you right next to

the individual with the longest fingernails. But really, in a way, you have

become this planet’s contemporary travel guide.

WH: I like to have companions, and to take them along, but it’s not like exploring different landscapes and going to Antarctica. Any idiot can go to Antarctica. But it’s a voyage, and you can see that in particular in my feature films. It’s exhilaration; it’s this kind of real storytelling and taking people along. That’s more important than enumerating, Yes I have shot in Australia, and yes, I have shot in Europe, and yes, I have shot in Mexico, and yes, I have shot in Antarctica.

SF: Don’t you feel you have a

genuine grasp of life on Earth?

WH: No, no, any travel agent can go out and check the hotels.

SF: But you intimately spend time at

these places.

WH: And I’m working with people, but it’s something different that’s more important—that I’ve traveled on foot, and it’s never translated into a movie, but understanding the world comes from someone who has been out on foot.

SF: On foot is important to you.

WH: At least for me, and I say this as a dictum: The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot. Period.

SF: Earlier, you mentioned

exhilaration in your work. When are you most satisfied by your art?

WH: When I cook a steak really well.

SF: A steak?

WH: A beef steak. Really well done and sizzling in front of you, and you share it with your guests. Cooked to perfection, as it should be.

SF: What is it about that?

WH: There’s nothing more exhilarating.

SF: In making this film, what

information were you most surprised by?

WH: I think nothing really surprised me because looking at what’s going on around you, you get a grasp of events that are happening or that are coming. But maybe the most surprising single thing was mind-reading: that you can read the radio waves that come from your brain from a short distance with an MRI scanner. You can read these brainwaves, where somebody who reads a text in English and somebody who reads the same text in Portuguese can create a different wave pattern that you can understand. There are certain structures that articulate themselves in a variety of grammars in different languages.

SF: And where does love fit

into this equation?

WH: What about the dishwasher that falls in love with the fridge? Let’s put it this way: In the film, it can be seen and felt that I love everyone with whom I talk. There’s a great warmth and appreciation. But, otherwise, let’s say, real love occurs among ourselves as human beings. It has to be in a different film. Like Queen of the Desert, a feature film.

SF: At its core, Lo and Behold feels like a portrait of

humanity.

WH: That’s why no one else had made this film so far. It needed me to step in and get into the mess.