It all started off humbly enough. It was a forum dedicated to a band that came out of Glasgow in 1996, and the very first email, sent in 1997, set things in motion with a deceptively simple premise: “The Sinister mailing list was setup by Paul Mitchell in August 1997 to assist David Kitchen’s efforts to create information about the band Belle and Sebastian.”

But that doesn’t come close to describing the breadth of material that has accumulated in The Belle and Sebastian Email Mailing List over the past 20 years, resulting in what resembles a rough draft of a massive novel in which the characters are all startlingly alive, even if the plot remains discursive. The notion of a fan email list also doesn’t capture just how frequently, eloquently, and hilariously the emails depart from the topic of Belle and Sebastian completely, the band becoming the thinnest of tissues, more of an inspirational sensibility, connecting an altogether different kind of internet community.

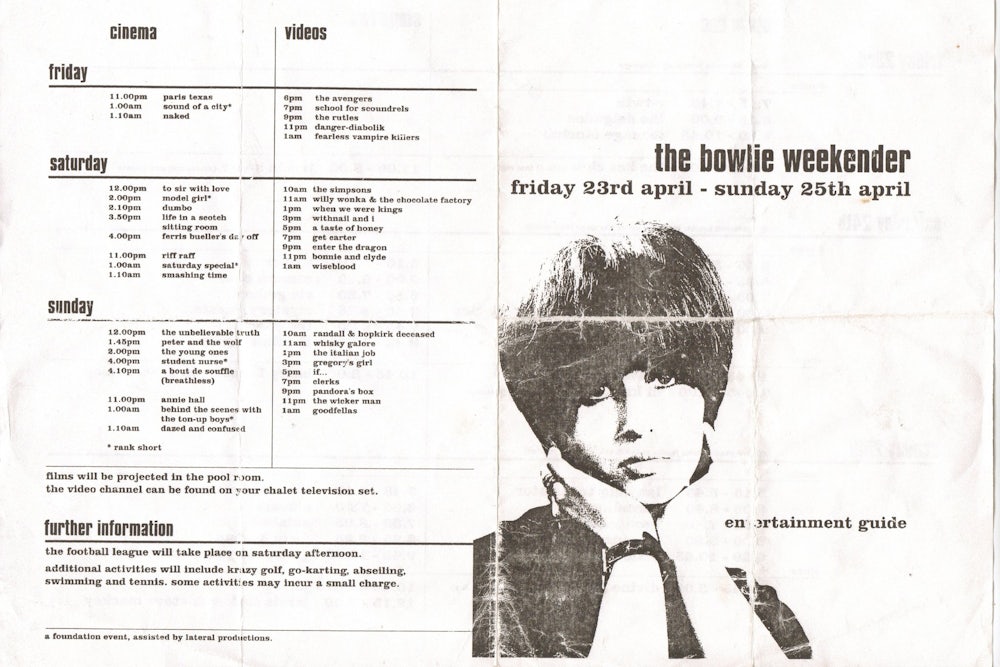

A typical email would begin by discussing how “all this talk of Czech weather and soft-core pornography has inspired me to speak up and introduce myself”; or how someone has “a bellyful of wine and passiflora” and “still can’t sleep”; or how another gets “mocked for having Nietzsche under my bed … not a book … the actual german philosopher.” Actual friendships formed through the list; one former list member, Joe Brooker, told me that he “came to meet people who made music, and thus … ended up making records and playing live as a direct result of all this.” And after a while everyone clearly knew everyone else, to the point where one man told the list that he was “ponder[ing] the idea of a Sinister retirement village, an everlasting bowlie weekender/perpetuality-er.”

Reached by email, one of the original site moderators, who asked not to be identified, told me that he considers the mailing list and the subsequent archives “something of a symbol of a bygone age when the Internet was less corporate and people talked at a greater length about their lives.” Advice was shared (“the hostel above kelvingrove is okay but b & b’s are better for creature comforts (are you a creature?)”). Contributors met up. “People started having ‘picnics’ as the term became fairly early in list history,” he said, with photographs on the site to confirm it.

“I can’t remember who started it, but I bet it was an actual picnic, and mostly continued that way but always ended up in a pub or concert,” he told me. “People from the list had these all over the world, made friends, and I know many cases of people who met on the list, married, [and] had kids because of it.”

It initially had about 1,000 members, the FAQ page informs us, and was established “one afternoon in August 1997 for a laugh.” As the FAQ notes, “The list is run from Scotland, so it’s pretty close to home, and many of the members are friends of the band—the band sometimes mail and often read too.” After you’ve subscribed to the mailing list, there is a waiting period of two to three weeks so you can get a feel for the unique tone of the list, which, like Belle and Sebastian’s music itself, can be both arch and whimsical. “Compose your message,” we’re informed, “hover your hand over the send button for 10 seconds—think: ‘would Cliff Richard or the Dalai Lama send this?’—send if the answer is still ‘yes.’”

Lawrence Mikkelsen, a teacher in New Zealand and a

co-founder of Lil’ Chief Records, is a former list contributor. (One of his

emails has him jokingly referring to himself as a “beagle

howling in a wind tunnel.”) He offered up one perspective as to

why the list grew.

“Information about the band was really scarce at the time,” he said, “virtually no press photos, very few articles in music magazines, so I felt like I’d joined this benign little cult. … I also remember how long I’d take writing messages ... pretty much everyone really put a lot of effort into their posts. There were lots of genuinely interesting writers on there, and lots of moments where I’d laugh, or be genuinely moved by posts.”

He “still thinks the Sinister list is the gold standard for internet communities—nothing else has ever come close in terms of having a critical mass of genuinely good people.”

More than the list’s benign cultishness may be at work here. Geography, and particularly the list’s physical locus in Glasgow, likely played a role in the list’s success as a social network. Michael Seman, a research associate at the University of North Texas who specializes in how music relates to economic development, told me that while he hasn’t “come across an eccentric fan community that informs the music economy of a city in a specific way,” there are plenty of “site-specific events facilitated by eccentric music communities” like the Gathering of the Juggalos in Thornville, Ohio, and Phish’s weekend events (The Great Went, Lemonwheel, Camp Oswego, Big Cypress, It) in various places across the country.

“Each of these events only happen due to fervent fan bases that are eccentric enough in their own ways to travel to arguably tiny, remote communities for a long weekend,” Seman continued. “The general indie community has somewhat similar, eclectic—but not necessarily eccentric—fan-driven events like Basilica Soundscapes in the Hudson River Valley and the recent Marfa Myths event in Marfa, Texas.”

The band liked the list, too. “We loved what those guys from the Sinister mailing list were doing on the fledgling internet,” Stuart Murdoch told Loud and Quiet in August of last year. “They were giving two fingers to the press and the zeitgeist of the time, quietly, in the same way we were.”

Such mutual admiration is rare in a band’s relationship with its fans. It speaks to the way bands and fans can exist symbiotically in the digital age, and the list is a very sophisticated example of the way fans work out their own thoughts and feelings through a band’s work, which is what is happening at some level whenever you find yourself deep into a record.

“I still glance [at the Mailing List] sometimes,” Alastair Fitchett, a former list contributor, told me. “Revisiting that has been helpful for me mostly by reminding me of what’s important in terms of giving me pleasure. ... I wrote fanzines in the ‘80s and early ‘90s and through that I had a fairly wide global network of friends to whom I would write. The letters we wrote seemed as important as the fanzines themselves. Probably more so. It was in the letters that I found myself thinking through ideas. I know other people felt the same.”

There are a few obvious beats to hit when it comes to talking about how fans interact with musicians and bands online today. There are Beliebers, who have flooded every known social network. There are highly quotable Reddit AMA threads. Artists release whole albums without a word of warning, skipping the traditional middle men and hype machine that can stand in the way of a direct musical experience. Bandcamp, Soundcloud, and Facebook fill up with independent artists clamoring for attention. And you can find and champion artists who might never get the traction they absolutely should get.

There are quirks of old-fashioned email, however, that may allow for greater creativity and self-expression than a Facebook template. The research shows that “people still spend half their workday dealing with [email], they trust it, and overall they’re satisfied with it,” according to Harvard Business Review. “It’s becoming a searchable archive, a manager’s accountability source, a document courier. And for all the love social media get, email is still workers’ most effective collaboration tool.”

But I’m not here to tell you that blogging is dead or that email “isn’t dead, but evolving.” What is interesting is the way certain experiences, certain phenomena, can become collective ones. For a small window of time, there was something charming about using your college email address to sign up for a new site called Facebook. For a small window of time, there was something charming about the groups that formed through Tumblr. For a moment, there were shared experiences that weren’t cramped by groupthink or torn apart by anonymous trolling. And it’s easy to see how that sweet spot could be hit through an email list, a medium that is a little closer to traditional letter-writing.

At the opening of her memoir, Carrie Brownstein writes that nostalgia is “so certain: the sense of familiarity it instills makes us feel like we know ourselves, like we’ve lived. … Though hard to grasp, [it] is elating to bask in—temporarily restoring color to the past.” The emails collected in the Sinister archive exist not only as information on a server, but as a password to a world beyond Glasgow and the one between your headphones. Speak the password, and you get another sunny day where we met for a picnic. Don’t speak it, and it might just disappear.