I don’t suppose that when my parents sent me off to the University of Virginia Young Writers Workshop they imagined I’d return, a few weeks later, both gay and an objectivist. Fortunately they were wise enough to understand the former as something indelible and the latter as a phase, which they amusedly tolerated. In fact, my mother had given me a copy of The Fountainhead the year before; like any wishfully pubescent teenage loser, I devoured it in a couple of sittings, but if I ascertained in its pages some proof of my own self-evident heroic genius, the notion that the novel represented a Weltanschauung escaped me.

The Young Writers Workshop took place over three summer weeks on the outskirts of the UVA campus, far beyond the neoclassical charm of Thomas Jefferson’s academical village where the practical necessities of dorm tower blocks and cafeterias dictated a more stolid, if still leafy, environment. On weekends, the Workshop made efforts to get its religiously inclined attendees to churches and prayer meetings and so forth. I considered myself an atheist, so I wandered into a meeting held by a couple of our counselors that was billed as Atheist-Objectivist.

The second word meant nothing to me; I found myself at once aghast and fascinated as both the counselors and the other teenage non-believers quoted giddily from Ayn Rand’s vast body of work. For a bunch of godless heathens, they seemed oddly reverential, but every weird teenager secretly desires a gang of fellow iconoclasts: It’s much easier to be different together. I also met a cute boy that summer, who happened to live not very far from me on the other side of Pittsburgh, but the man who really changed my life was a fellow you may already have heard of. His name was John Galt.

Ahem. Who is John Galt? Galt is the mashiach of the Randian cosmos, the savior-judge whose incarnation marks the inflection of one era to the next. But unlike Jesus, say, who sacrificed himself that you might live, Galt, the hero-manqué of Atlas Shrugged, Rand’s immense magnum opus, simply absents himself that the rest of us might burn, reappearing to claim the pile of ashes. I had never heard of John Galt, or Atlas Shrugged for that matter, but I was quickly disabused of my ignorance. The Fountainhead was a fable for children; Atlas was the Word. And though I didn’t actually read it until the following school year, I found it, even in the abstract, immensely appealing. Galt—like the boy heroes of the science fiction that I also loved—was the perfect adolescent savior, a comic-book supervillain cast as a superhero. “I will stop the engine of the world,” he bragged. Like so many conversions, mine required less theology than brief flash of grace. In a student lounge in a vaguely Soviet dorm on the expensive campus of a fancy college, I was converted.

Over the next school year, I used a fair portion of my slim earnings as an office assistant at the State Theatre Center for the Arts, the “Grand Old Lady of Main Street” in Uniontown, PA, to purchase a full paperback library of Rand’s novels and non-fiction. Their covers all featured heroically angular illustrations that—an irony I didn’t quite detect at the time—looked like pastiches of WPA murals, Soviet propaganda posters, and the architectural imagination of Albert Speer.

In his marvelous 1957 review of Atlas Shrugged (“called a novel only by devaluing the term. It is a massive tract for the times”), Whittaker Chambers noted “that the author has, with vast effort, contrived a simple materialist system, one, intellectually, at about the stage of the oxcart, though without mastering the principle of the wheel.” He does grudgingly admire the book’s “bumptious” energy, though.

Yet this is also, by his description, the sniffy disdain of an “upperclassman,” presumably at one of the better colleges. To a disaffected teenager, Atlas serves as a thrillingly direct indictment of the whole damn system, man. The government is hopelessly corrupt. Society is hopelessly corrupt. But for a few men of genius—the reader is implicitly invited to imagine himself as one of these, even if Rand herself would’ve disdained the pimply physical defectiveness of her lumpen adolescent readership—the world would be a morass of totalitarian misery. Let the world burn, and out of the ashes arise a new order!

I spent my junior year of high school styling myself—politically at least—as a kind of queer fascist libertarian, a political platypus, firmly convinced that if those geniuses and businessmen were to fuck off to an isolated gulch somewhere in order to let the rest of humanity’s second-raters self-immolate in an auto-da-fé expiation of their corrupt, mooching ideology, then by God (a base superstition, by the way; a violation of Ayn Rand’s great insight that A is A!), I’d be invited to fuck off with them. To assure my place, I even entered the Ayn Rand Institute essay contest, which promised a grand prize of something like ten thousand dollars. And I was actually one of the named honorable mentions, but I didn’t make the podium, and I didn’t win any cash. This immediately soured me on the whole enterprise—also, I’d discovered sex and weed, though, if I’m honest, my participation in either of these was usually more notional than actual. I’d finally started to grow into my own body, but I remained the sort of gawky adolescent who stays at home reading The Virtue of Selfishness while listening to the prog rock of his father’s generation.

Although in the current election season the Republican Party has drifted toward a blood-and-soil nativism with vague overtones of a militant Christianity—none of which would particularly appeal to a real Objectivist—there remains, in the party and in its candidates, a certain rhetorical affinity for Rand’s uncompromising brand of juvenile laissez-faire. “These regulations. Come on!” said John Kasich at the last debate, as if there existed a categorical rather than particular evil. Rand “Not Named After Ayn Rand Thank-you-very-much” Paul has cited her, along with a few economists of the so-called Austrian School, as an early influence. Back in 2013, Ted Cruz spoke glowingly of her apocalyptic vision for the social welfare state when he joined Paul’s filibuster of John Brennen’s nomination as director of the CIA. “One of my all-time heroes,” he said at the time.

As you can imagine, they’ve all toned down their love affair with the famously atheistic Rand for the GOP primaries. Nevertheless, she has a durable following among the conservative political class. There are few scenes more appalling hilarious than Justice Clarence Thomas, each year, inviting his new law clerks to his home for popcorn and a screening of The Fountainhead, the King Vidor-directed, Cooper-and-Neal vehicle that’s high in the running for the worst movies of all time—a thing that really happens.

But there is a tendency among mainstream liberals, the sort of people who flatter themselves as “progressive” while supporting the same hack Democrats election after election, to sneer at this enduring fascination with the crackpot Russian émigré as a testament not only to Conservative heartlessness—she famously compared people on welfare to leeches and parasites—but, more damningly perhaps, as a sign of never-ending adolescence, a signal that these guys (they are mostly guys) never grew up and got responsible politics.

But of course, responsible politics have delivered us a perpetual War on Terror, a panoptical crypto-police state, bank bailouts, and the ever-yawning gap between the new rentier class and the rest of us, none of which Barack Obama, less yet another Clinton, seems especially inclined to do anything about. Even Bernie Sanders, the most progressive of progressive candidates, is hardly more than a milquetoast European Social Democrat, barely radical in the American context and not radical at all if viewed in a more global political spectrum.

Rand is generally treated as a figure of the crackpot right, which isn’t entirely fair. Her scientific (or pseudoscientific) anti-clericalism, for example, owes as much to the French Revolution as it does to any conservative ideology. If she vehemently rejected the internationalism of communism, then she also rejected the ethnic nationalism of the right. She hated totalitarianism and proposed herself a kind of meritocrat, but there is, in her work, a barely concealed longing for an aristocracy; not by accident are many of the industrialist heroes of her fiction actually heirs and heiresses. Even as you outgrow her, she appeals to the part of you that rejects the neat taxonomies of politics in the West.

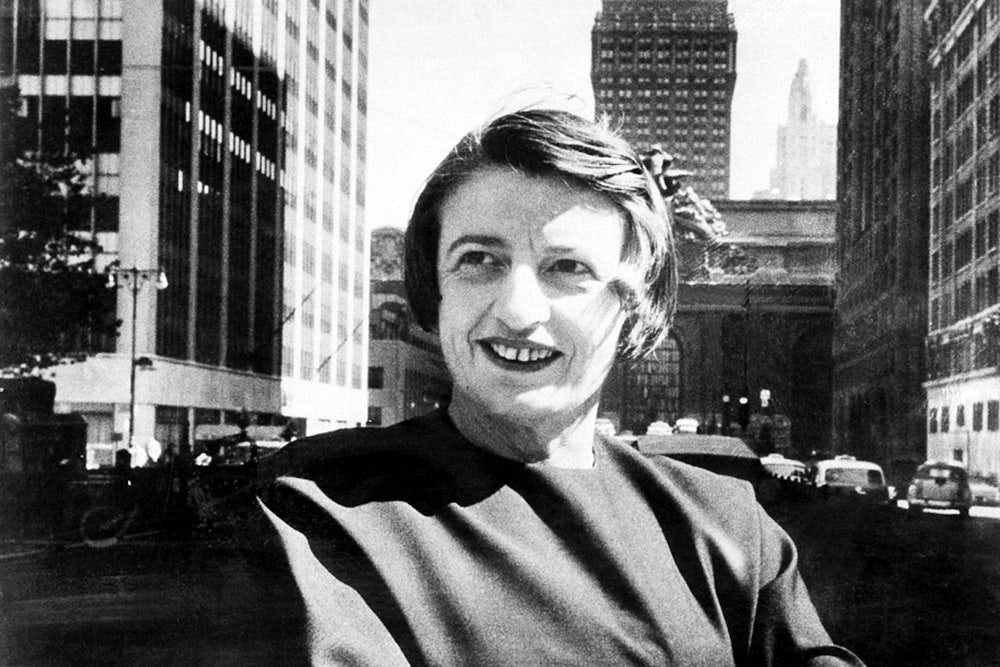

As for me, I’ve never quite figured where to place myself on a left-right spectrum: a moralist but a moral relativist; a queer atheist with an enduring affection for the most traditional of religions; an anarchist by intellect but a collectivist by sentiment. I do count myself a radical, and even if my later development as a political writer and thinker owed a great deal more to Didion and Vidal and Ishmael Reed and a lot of crackpot early-aughts bloggers, then it would still be no exaggeration to say that my earliest, most formative, and most enduring encounter with a radical politics was the high priestess of The Collective herself, Ayn Rand.

“Individual rights are not subject to a public vote; a majority has no right to vote away the rights of a minority; the political function of rights is precisely to protect minorities from oppression by majorities (and the smallest minority on earth is the individual).” Get it, girl! It was Ayn Rand who suggested to me that there existed a place for political thought and political affinity beyond the meager push-pull of American electoral politics; that perhaps Clinton-Dole or Bush-Gore did not in fact express the widest range of thinking about the proper structure and operation of a human society. Words that appear nowhere in her major works: Democrat, Republican. It’s another ironic truth that her utter and absolute commitment to the supremacy of individual rights, including a total rejection of a notion of the common good, made me more receptive to the ideas of Marx or Prudhon, because she taught me, in the same year as I was learning the opposite lesson in A.P. American Government, that the electoral viability of this or that Congressional candidate was not the be-all and end-all of a person’s politics.

Rand’s actual philosophy, such as it is, is pretty gross, as are the stunted grown men who imagine her as a world-historical intellect rather than a horny materialist who misread Aristotle. But insofar as a high-school student is more likely to encounter The Fountainhead than Das Kapital—or for that matter, A People’s History of the United States—there seems to me to be an intrinsic value in her writing that exists almost separately from the specific import of her limited ideology: in this case, something categorical rather than particular. It is salutary for young people to encounter radically different ways of thinking; it’s good for them to see a hostile reaction to the established order; and it’s immensely condescending to assume that they’ll all end up as smarmily self-satisfied Ted Cruzes because of it. If a thousand pages of rough sex and bonkers speechifying offers even a few kids a sense that political philosophy can comprise something greater than “How a Bill Becomes a Law,” then it’s something to be encouraged. Just because something is worth growing out of, that doesn’t mean it’s worthless. I don’t smoke weed much anymore, either, but I don’t regret that I did.