National Review is the great intellectual gatekeeper of the American right, a journal of opinion that has long served as the arbiter of what counts as respectable conservative thought. Throughout its six-decade history, the magazine has been known for launching crusades against ideological factions it regards as unworthy of belonging to the conservative tribe, including anti-Semites in the late 1950s, libertarians and members of the John Birch Society in the 1960s, and anti-war conservatives in the 1990s and post-September 11. Acting as a kind of bouncer, National Review has earned enemies who accuse it of purging dissident thought on the right. But there’s no question that the many wars National Review has fought to purify the conservative movement have often had a salutary effect, particularly in excluding anti-Semitism and more overt forms of racism.

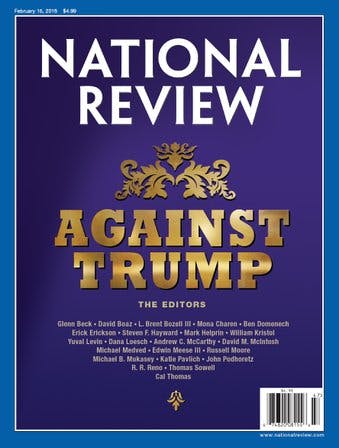

So when National Review launched its special issue “Against Trump” last night, it was keeping to a venerable tradition of policing the right. The magazine has been fiercely skeptical of Trump since he announced his candidacy last summer, but the special issue, which boasts an array of right-wing media personalities and pundits as well as a feature editorial, seems designed to be its definitive statement, a historical milestone on par with William F. Buckley’s denunciation of the John Birch Society in 1965 or the magazine’s rejection of Pat Buchanan’s anti-Semitism in 1991.

Yet, despite some good polemics, “Against Trump” is a weak-tea effort. Too much time is spent trying to prove that Trump is not a real conservative, while ignoring the fact that the racist nationalism he is espousing has its origins on the right. Trump, the editors argue, is “a philosophically unmoored political opportunist who would trash the broad conservative ideological consensus within the GOP in favor of a free-floating populism with strong-man overtones.” There’s much that can be questioned here: After all, National Review didn’t have a problem with “free-floating populism” in 2008 when it celebrated Sarah Palin (now an enthusiastic Trump cheerleader), and historically the magazine has loved strongmen dictators like Mussolini and Franco.

The symposium gets off to a rocky start by beginning, admittedly for alphabetical reasons, with a contribution from Glenn Beck. With his long history of racism and conspiracy-mongering, Beck has all the flaws of Trump many times over. To get Glenn Beck to denounce Donald Trump as an unsound thinker makes about as much sense as hiring Larry Flynt to write about how Hugh Hefner demeans women. Nor is Beck the only extremist in the symposium, which also includes contributions from Erick Erickson (known for his boorish sexism) and Thomas Sowell, who in 2007 wrote in National Review: “When I see the worsening degeneracy in our politicians, our media, our educators, and our intelligentsia, I can’t help wondering if the day may yet come when the only thing that can save this country is a military coup.”

In the “Against Trump” symposium, Sowell makes this outlandish comparison: “The actual track record of crowd pleasers, whether Juan Perón in Argentina, Obama in America, or Hitler in Germany, is very sobering, if not painfully depressing.” Is there any rhetorical overkill Trump has been guilty of that is worse than this?

Sowell’s belief that a coup could be good for America and that Obama can be fairly compared to Hitler gives lie to the argument, made repeatedly by writers in the National Review symposium, that Trump is not a true conservative. For there is very little that Trump has said or done that can’t find prior sanction in National Review, be it racism, anti-immigrant nativism, or sexism. In the last debate, in response to an attack on his “New York values,” Trump noted that conservatives do come from New York and cited William F. Buckley. It is fair to see Trump’s version of white identity politics as firmly in the tradition of Buckley and his magazine.

Decades from now, when historians try to figure out the genealogy of Trumpism, they will have to pay careful attention to the pages of National Review in the 1980s and 1990s, when a crucial debate was being played out between neo-conservatives and paleo-conservatives. Although National Review ultimately sided with the neo-conservatives, it gave ample room to such paleo-conservative voices as Joseph Sobran, Peter Brimelow, John O’Sullivan, and Samuel T. Francis. Even after these writers were purged from the magazine, the white identity politics they argued for was taken up by other National Review writers, albeit in more muted and coded form. This paleo-con tradition created the idea of a politics centered around immigration restriction and a more robustly nationalist foreign policy (including trade policy). Many of these writers seeded the ideas that helped form the alt-right, which is the faction on the right that is most enthusiastic for Trump.

In truth, the relationship between National Review and Donald Trump is like that of Victor Frankenstein and his monster. Horror-stricken by what the monster is doing, Frankenstein might deny his own creation and say that it has a will of its own. But without Frankenstein, there is no monster. And without a conservative movement that fostered and indulged white identity politics, there is no Donald Trump.