Early film historians have the unhappy lot of repeatedly

needing to remind non-specialist readers that whatever assumptions they’ve inherited

about the movie’s first decades are basically wrong, or incomplete, or given with

the stress in the wrong places. Early movies, they insist, were often not

screened in black and white, and hardly ever in silence. Many of Edison’s

accomplishments, they admit, are better attributed to his lesser-known

collaborators. And the first films were not, they caution, the charmingly naïve

productions they sometimes seem to be.

If there is a single thought behind the recent boom in scholarly research on

what we think of as “early cinema”—the period lasting roughly from the

introduction of projected film screenings in 1895 to the emergence of the production

company as a dominant presence in the early 1910s—it’s that early

movies were neither innocent in their intentions nor benign in their cultural

and environmental effects. From the beginning, the movies were blessed with the

knowledge that they were aggressive, threatening presences in the rapidly

changing cities and rural sites they were designed to record. Early filmmakers

gravitated in the direction of subjects that seemed to defy nature in the same

way that the movies did themselves: convoluted acrobatic routines, superhuman displays

of strength, magic acts, fairy tales and dream films, showcases for inventions,

exotic travelogues, Passion Plays. Even “actuality” films such as Porter’s Coney Island at Night (1905) or Billy

Bitzer’s Interior NY Subway 14th Street to 42nd Street (1905) may have been, as Brian R. Jacobson

argues in his recent book Studios Before

the System, in fact something closer to demonstrations of force, proof that

the worlds in which moviegoers lived and moved could be re-purposed as sets.

Jacobson’s is one of a handful of recent books to call attention to an under-studied aspect of the movies’ first two decades; it does for studio architecture what Joshua Yumibe’s 2012 study Moving Color was meant to do for early color processes and what Jennifer Lynn Peterson’s 2013 book Education in the School of Dreams did for commercial travelogue films—short, educational documentary portraits of exotic locales. If there was a single argument that dominated the turbulent period in cinema history these books address, it was over what rendered movies lifelike, natural, or real. When a filmed bout between the boxers Robert Fitzsimmons and Jim Corbett became a touring sensation, the enterprising distributor Siegmund Lubin hired Fitzsimmons to spar on camera with a Corbett lookalike. Once a Little Rock audience realized that their theater was screening a dupe, according to one account, the policemen on hand “could no more restrain the impatient and thoroughly exasperated crowd from rushing pell-mell at the box office than human hands could push back the Johnstown flood.”

Scenes like this seemed to come from a widespread form of the anxiety that the film theorist Sigfried Kracauer claimed to have felt after touring UFA’s studio village in 1926. “The things that rendezvous here,” he wrote, “do not belong to reality. They are copies and distortions that have been ripped out of time and jumbled together. They stand motionless, full of meaning from the front, while from the rear they are just airy nothingness.” He was giving voice to a worry that seems to have been in the air at the time—that a mutually beneficial, happy relationship would never be able to emerge between films and the worlds they purported to depict.

Many of America’s earliest moving images—the short records of tricks, dances, performances, and vaudeville acts that W.K. Dickson shot for Thomas Edison between 1893 and 1895—were filmed against cavernously dark backgrounds. Watched together, they would have suggested a variety show of the very barest means, staged so that the eye had no choice but to linger on whatever oddities—boxing kittens; cavorting Indians; flexing bodybuilders—happened to be gathered at the front of the shot.

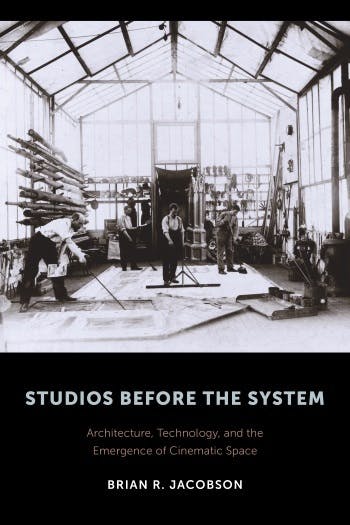

The dark backgrounds in question belonged to the hangar-like studio space Dickson designed at Edison’s New Jersey laboratory complex in 1892. At the time, Dickson and Edison were developing the Kinetograph, a camera meant to produce moving images for the single-viewer peepshow devices (“Kinetoscopes”) the company was then introducing, and the studio was built to accommodate the new machine’s demands. Having grasped that the camera’s subjects would show up more sharply the darker the space against which they were framed, Dickson constructed a velvet-lined tunnel that extended three feet back from the studio’s stage. Realizing that the Kinetograph best detected subjects lit by lavish amounts of natural light, he gave the studio a retractable roof through which sunlight could pass and built the entire structure on a rotating platform, which a staff of hired hands would turn as the day advanced.

“With its great flapping sail-roof and ebon [sic] complexion,” Dickson wrote in 1895, the studio had “a weird and semi-nautical appearance, like the unwieldy hunk of a medieval pirate-craft…and the uncanny effect is not lessened when, at an imperceptible signal, the great building swings slowly around upon a graphite centre, presenting any given angle to the rays of the sun.” Inside, it was cruelly hot. Lab hands derived its nickname, the “Black Maria,” from its resemblance to an oversized paddy wagon. For Jacobson, the studio epitomized the hope early filmmakers shared with turn-of-the-century architects and urban planners “to make natural light a technological form.” It was designed in every particular to “dissociate filmmaking from the strictures of nature”—in other words, to put as many of the conditions that made filmmaking possible under human control.

During the period Jacobson covers, film producers and studio

architects were remarkably quick about finding ways to reduce their dependence on

daylight, favorable topography and good weather. By 1909, filmmakers were combining

natural light with, in Jacobson’s words, “a shifting and uncertain combination

of various forms of glass, diffusing cloths, reflectors, Cooper Hewitts, arc

lamps and incandescent bulbs.” The seminal studio that Vitagraph established in

Flatbush around the same time was a large rock-faced building equipped with

prismatic windows and roofs through which the movement of light could be

carefully controlled. By that point, Gaumont’s Cité Elegé—the studio complex

it established just outside Paris in 1898—had expanded from one small building

to three formidable ones; as of 1913, it was a factory-like campus of two-dozen

separate facilities and at least three smokestacks.

Film production’s increasing reliance in the early teens on

location shooting and open-air studio backlots might be assumed to have

reconciled moviemakers to nature. Instead, Jacobson argues persuasively, it

simply changed the terms of their opposition to the natural world. Having once

poured time, money, and ingenuity into protecting their productions from cloudy

days and unpredictable rain patterns, producers were in a position by 1913 to

alter plots of woodland, marshland, or plains until those “natural” settings

resembled the controlled environments they’d become used to constructing. “The

best of all studios is Nature,” Jacobson relates an exhibitor writing in Motion Picture World. He makes much out

of a series of photographs, published in the same paper, of Cecil B. DeMille

and Jesse Lasky “prospecting for locations” like miners for gold. For

filmmakers like DeMille, Jacobson proposes, “location must have become much the

same as studio scenery—a resource that could be prepared, saved up and stored

for future use.”

The poignancy of Studios Before the System is that it lingers over a kind of early studio that did promise a less rapacious, happier relationship between filmmakers and nature: the “glass house” design that achieved widespread popularity in the nineteen-aughts, only to fall out of use as artificial lighting improved. Buildings like the pioneering iron-and-glass studio Méliès built in 1897 in Montreuil-sous-bois, the rooftop studio Edison inaugurated in 1901 on the Lower East Side and the enormous frosted cathedral at the center of the Cité Elegé were modeled after universally known works of nineteenth-century European architecture (the Winter Garden; the Crystal Palace; the Galeries des Machines), and soon enough more practical and cost-efficient methods emerged to meet the camera’s needs.

But the studios that replaced these glass houses never recaptured the delicate rapport they established with their natural surroundings, on which they relied selectively, respectively, and with a kind of moving openness. Méliès’s glass studio let in so much light that, as Jacobson relates in his book’s last pages, it served as a makeshift, weed-covered greenhouse decades after it closed.

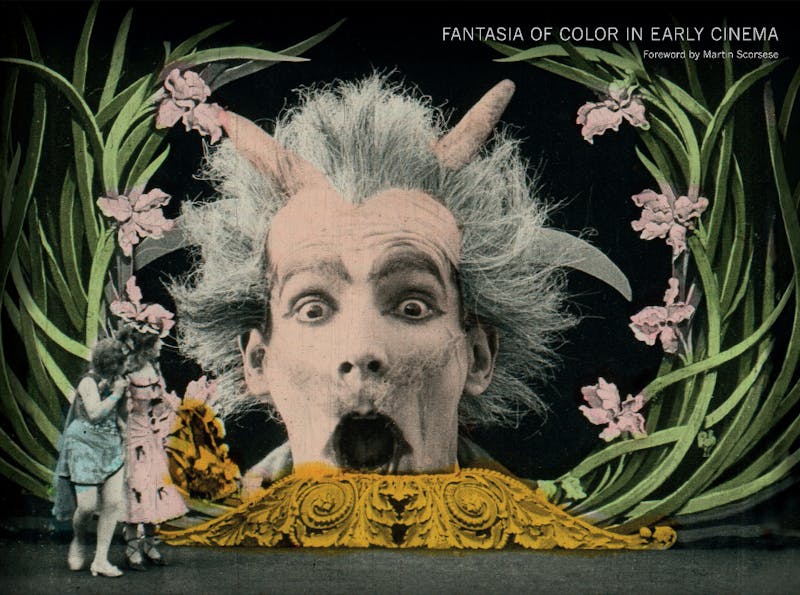

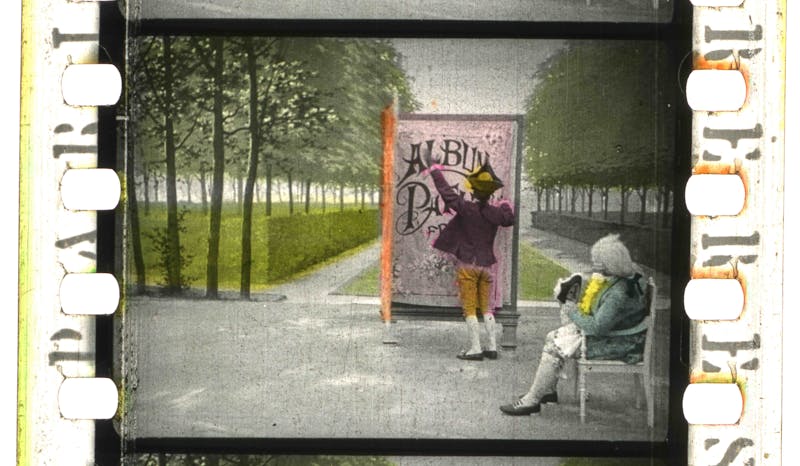

That Méliès shot most of his films in a frosted glass gallery flooded with natural light would have been lost on many of his original viewers, who would have seen his movies in what was then their preferred state: radiantly, sometimes garishly color-dyed frame-by-frame. Like early studios, early coloring techniques—almost all of which were applied to films after they’d already been shot—were at once feats of creative ingenuity and proof of how far the movies’ relationship to nature could be stretched. Looking at the hundreds of stills from tinted and hand-colored silent movies collected in Fantasias of Color in Early Cinema—a new archival picture book assembled with great care by Gunning, Yumibe, the archivist Giovanna Fossati, and the fine artist Jonathan Rosen—suggests precisely what made early color so unnatural. By transforming each frame of a film into a one-of-a-kind painted object, hand coloring called attention to what early films were otherwise at pains to conceal: the fact that movies, though they appeared to show unbroken movements, were in fact nothing but strings of discontinuous still images. Motion pictures in this period of early color became something like flipbooks of isolated, hand-painted still frames—objects not unlike the one Gunning, Fossati, Yumibe, and Rosen have now compiled.

Of the coloring techniques in use during the movies’ first twenty years, multi-color dyeing by hand was at once the most effortful and the most dazzling in its results. In contrast to tinting (which involved soaking the white regions of a filmstrip in a single dye) and toning (which entailed dying the film’s dark patches), it could never be carried out on an entire strip of film at once. Until 1905, filmstrips were painted frame-by-frame, using miniscule camelhair brushes, by assembly lines of meagerly paid female laborers. (“It was believed,” Gunning remarks in his introductory essay to Fantasia of Color, “that women’s fingers were more nimble.”) Since no device existed with which to copy a colored filmstrip, each print of a movie had to be painted afresh.

Stenciling, which Pathé’s engineers introduced midway through the aughts, corrected that problem. It was found that tracing styluses could be connected to pantagraphs—machines that resembled microfilm viewers or flatbed microscopes—and used to cut out stencils of 35mm film stock that corresponded to each of the colors in a given frame. A series of single-color dyes, at that point, could be applied mechanically to each strip in a batch of prints. In the earliest hand-colored films, colors tended to extend quaveringly beyond the objects to which they were supposed to belong. These later, stenciled films seem to come from a world in which colors and their corresponding subjects have been re-united, but somehow precariously. As Gunning observes, “Even when the coloring-in of objects has been carefully done… an impression persists that the color hovers over the object rather than inheres in it.”

If the stills collected in Fantasia of Color, many of which come from Edison and Pathé films preserved in Amsterdam’s EYE Film Institute, don’t give a sense of this hovering effect, they suggest much about the sheer, uncanny strangeness color conferred on early films. They produced especially ghoulish effects when applied to fairy tale movies or films documenting magicians’ tricks. (In a still from a 1903 Pathé adaptation of Puss in Boots, a king flinches at the static presence, near the rightmost edge of the frame, of a bright red bear standing rigidly on its hind legs.) And yet, like breakthroughs in studio architecture, breakthroughs in color affected movies both conventionally “realistic” and outwardly fantastical. Whimsical illusions of the sort associated with Méliès and Chomón were hand-colored, but so, the book shows, were travelogues set in the Swiss alps, local actuality films like Gaumont’s Dutch Types (1914) and antiwar propaganda efforts like Maudite soit la guerre (1914). In a frame from Pathé’s 1911 restaging of the infant Moses’s discovery in the Nile, a princess’s attendants walk in a double-file procession sheathed in pale, purple gossamer dresses. It’s another poignant aspect of Fantasia of Color that, as more than one of the book’s contributors stress, the colors it reproduces are particularly difficult to preserve. To keep them this vivid involved efforts as strenuous and fine-grained as the work it took to color them in the first place.

“Photography should have been invented in color,” Jean-Luc Godard intoned in a Kracauer-like tone over the soundtrack at one point in his multi-part video essay Histoire(s) du cinéma. But since it was designed “to reproduce life,” he mused, “to take away from life… it wore mourning for this putting to death. And so it was in the colors of mourning—black and white—that the photo began to exist.” The mystery, if one takes seriously Godard’s cryptic suggestion that the photographic image couldn’t do otherwise than “put to death” the bodies it was invented to record, is why so many filmmakers and distributors chose to decorate these solemn death-images with bright, intricate patterns of red, blue, yellow, and green.

Restored to their original, colorful state, these early films register less as tributes to a death than as celebrations of an ambiguous victory—the triumph of film producers, studio architects and colorists over nature’s inconveniences, mediocrities, and inflexible rules. Painted over, studio-shot films are something still farther from the direct representations of reality they’ve been periodically, naively taken to be. When they startle and mesmerize, it’s equally as mass-produced commodities and as odd, seductive works of imaginative art. Maybe never since in the history of the medium have those two categories been harder to distinguish.