A certain kind of American never tires of explaining that the country is a republic, not a democracy. Exactly what the distinction means can be obscure, but the drift is clear. “Democracy” is catching some shade: the people, that troublesome demos, is too feckless, passionate, selfish, and irrational to get by without adult supervision. Recently, Republican Congressman Devin Nunes praised “the difference between a democracy and a democratic republic,” and warned against the “unfettered kind of mob-style movements” that too much democracy can bring. Watching the current Republican presidential race, plenty of Americans may be inclined to agree.

The adult supervision is usually associated with anti-democratic features of the Constitution. It is not the people who make decisions, but their representatives in a government divided among the president, the two houses of Congress, and, of course, the Supreme Court. The justices of the Court are not representatives of the people. If they represent anyone or anything but themselves, it must be the Constitution itself, which, in the brief article that establishes the Court, assigns it “the judicial power.” Since an 1803 decision (in which James Madison was the defendant) the Court has repeatedly said, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” including the law that the Constitution spells out. If the Constitution ensures that the people act only indirectly and under watchful supervision, then the Supreme Court watches the watchers.

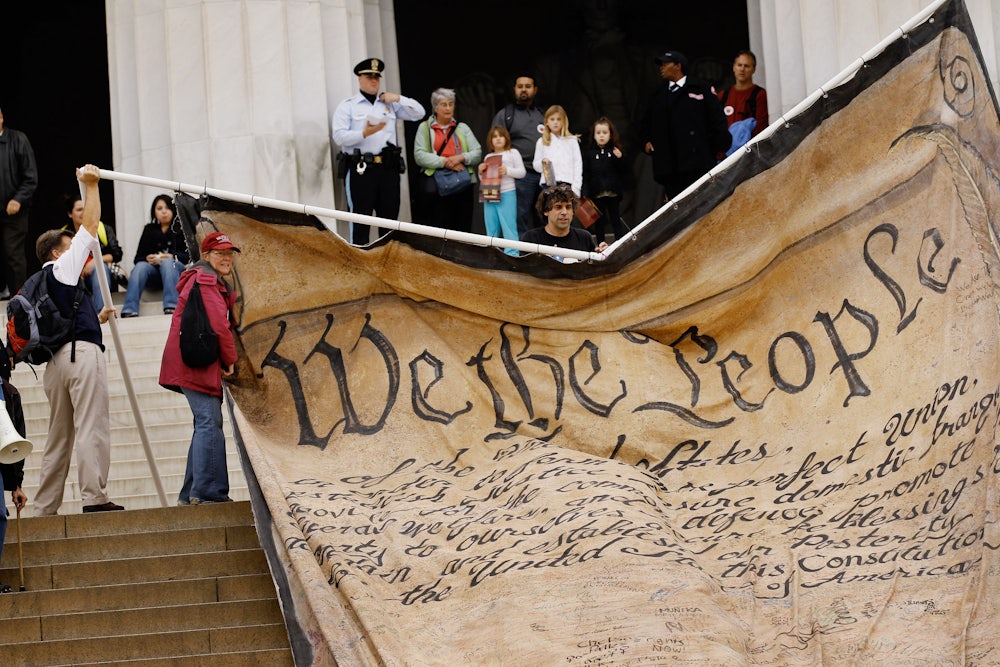

It isn’t just fans of the not-a-democracy-but-a-republic

school who treat the Supreme Court as a tribune of higher truths that float above

mere democratic politics. If there is an American civic religion, it is

constitutionalism. When the Court established marriage equality nationwide in

2015, it did more than hand a practical victory to would-be grooms and brides;

it said something about the identity of the We in the Constitution’s opening

passage, “We the People….” According to this civic religion, if a moral truth

is denied in constitutional law—as racial equality was in the age of

segregation, when the Court embraced the doctrine of “separate but equal”—it

must be latent in the principles of the document, waiting to be made true. From

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, to Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon

Johnson, reformers have presented themselves as constitutional redeemers, arriving

overdue on the stage of history to “form a more perfect union.” Even in the

Occupy Wall Street encampment in 2011, there were plenty of people who believed

that the inequality of American wealth and political power must somehow violate

the Constitution, and who hoped to set things back on their right foundation.

The Constitution’s special status is awkward in practice,

though. It becomes visible only when the Supreme Court declares some official

act—usually a law—unconstitutional. In these cases, the Court—nine old lawyers,

of whom five can carry a decision—denies the force of law to the present representatives

of a political majority. Known among lawyers as “the counter-majoritarian

difficulty,” this awkwardness has sent generations of scholars in search of a

distinction between politics and law. Surely political decisions belong to the “political branches,” and can’t

be vetoed by five judges in a weirdly temple-like building across the street

from the US Capitol; but law is what

judges say it is, and these anti-majoritarian decisions are, after all, the

ingredients of what everyone calls “constitutional law.”

For some four decades, the most influential candidate for

setting the boundary between law and politics has been originalism, the view

that Constitutional language should mean the same thing today as when it was

ratified (in 1789 for the original document and, for instance, 1868 for the

Fourteenth Amendment). That original meaning might lie in the minds of its

authors or the way the phrases were used in the public at the time. (Scholars

and judges have spent lots of time debating the difference, but they tend to

come to the same thing.) This was a very convenient argument when conservative

jurists were arguing against abortion rights and constitutional equality for women

and gay people. Originalism was a language of dissent, for people whose point

was to say, “Whatever ‘liberty’ and ‘equality’ meant in 1868, they didn’t mean

that!” The implication was that giving those constitutional terms new meaning

today was political decision-making, not legal interpretation, and therefore

illegitimate when a court did it.

Originalism’s importance has receded markedly in the last few years. The new intellectual leaders of the Supreme Court’s conservative wing, John Roberts and Samuel Alito, show little interest in any doctrinaire interpretive method, originalist or otherwise. Maybe they are too busy using the judicial power to bother tying themselves to a theory of how that power should be limited.

Be that as it may, originalism has also been looking intellectually unpersuasive as a compass for navigating the law-politics distinction. The original meaning of a phrase, after all, can be taken in many different ways. Adopting a constitutional principle of equality in 1868, for instance, doesn’t mean that you expect future generations to be bound by the interpretations that you would give it. The point of adopting such a broad principle might be that it will require interpretation in later applications, which might become very different over, say, 148 years. While it would plainly be un-originalist to ignore a specific rule—such as the Constitution’s requirement that the president be at least 35 years old—it is not necessarily un-originalist to say that equality has different meaning today than in 1868, and that what was adopted in 1868 was understood to be a principle that would change over time. Yale constitutional theorist Jack Balkin calls this view “living originalism.” Once we remember that liberals and conservatives alike can be originalists, there is much less motivation for anyone to take the trouble.

The most basic problem with originalism, though, is that it is just terrible as a theory of political legitimacy. This doesn’t matter much as long as you like the particular outcome being defended; but political theory has bite, if it ever does, precisely when it is time to explain to someone why she should go along with a decision she bitterly resents and which may even do her harm. Try explaining that Texas can outlaw abortion, North Carolina can forbid gay marriage, and—as originalist justice Clarence Thomas seems to believe—the courts should strike down much of environmental law—because of how they saw things in 1868 (or 1789). That was then. They are dead, and we are living. Didn’t that old slaveholder Jefferson say that the earth belongs to the living? Turning his formula into “belongs to the dead, as channeled by somewhere between five and nine judges,” is unpersuasive and arguably creepy.

But originalism’s total failure to give a good answer to the counter-majoritarian difficulty is only an acute case of the chronic and endemic problem of constitutionalism. Someone who reminds you that the country is a republic, not a democracy, is always telling the people, alive now and represented in their political institutions, to hush and take a (back) seat. And who, really, should get to do that? Constitutionalism may be a civic religion, but like some others, it is a holy mess at justifying its god’s (or its government’s) ways to man.

All this is why it is so refreshing to read Richard Tuck’s The Sleeping Sovereign. Tuck, a political theorist and historian of ideas, argues that the point of an eighteenth-century constitution (like ours) was not to limit democracy, but to empower it, even to rescue it from the dustbin of history. This is surprising because the counter-majoritarian difficulty has shaped so much of the American experience of constitutionalism in the last century.

A constitution, Tuck argues, was an answer to a problem that had long been thought insoluble: how could democracy, associated with the city-states of classical Greece, possibly be revived in the modern world? The eighteenth century imagined ancient Greek citizens constantly engaged in making the laws they lived under, and this seemed impossible for modern citizens, who (already more than two centuries ago!) were too numerous, dispersed, and busy with other things to spend their days in never-ending politics. If socialism would eat up too many evenings, in Oscar Wilde’s famous formula, so would democracy.

The genius of a constitution was that it gave the whole citizenry a way of making its own law: not by constantly engaging in self-government through assemblies or parliaments, but by occasionally mobilizing, through special institutions such as conventions and plebiscites, to authorize the fundamental law of their polities. A constitution was the law that the people authorized, directly rather than through their representatives. This power to make fundamental law was called sovereignty, and a democracy was a political community where sovereignty lay with the citizens. By contrast, the ordinary laws that legislatures passed were simply government, the apparatus that carried out sovereign decisions. Government, as Rousseau wrote, mediates between the sovereign, which makes the law, and the people, who live under it. In a democracy, government mediates between two aspects of the people: as democratic sovereign lawmakers, and as everyday law-abiders. Less mystically, government is what the mobilized people sets up to keep order after the sovereign citizens disperse to their private lives.

What difference does this make? Some contrasts are helpful. In this way of thinking, the distinctive thing about a constitution, its special interest and force, is not in the structure of government that it sets up, but in the theory of sovereignty that underlies it. It is true that the US Constitution has the democracy-baffling “republican” features that clog and divert political decisions, such as the divided Congress, the unrepresentative Senate, and the presidential veto. But these checks and balances were intended originally to keep the government from usurping the powers of the sovereign but dispersed people, according to whose collective will it was originally established.

On this theory, too, what makes a government democratic is not that it is rooted in and responsive to “the people” in some diffuse way, as the Supreme Court, the European Union, and the US legislative process all are. As Tuck emphasizes, there is nothing special in this idea, and both US lawmakers and Eurocrats give themselves undeserved congratulations for being “democratic” in this sense. Most medieval and early-modern governments claimed to have this kind of relation to the “the people.” The seventeenth-century Stuart “divine right of kings” was a marginal and rather desperate rationalization of monarchical power, which understandably loomed large in the imagination of American revolutionaries in the next century. The real ancien regime was consultative, operating in part through representative institutions like the French parlements and tracing its legitimacy to the people. It was simply assumed that there was no way for the people to act as the sovereign, so sovereignty was merged into the government—in the institutions and elites that held day-to-day power. Constitutional conventions and referenda provided a modern innovation, a way for the people to be sovereign once again by promulgating fundamental law.

The theory that Tuck has recovered from early-modern sources suggests a way of telling the story of constitution-making in America. When Massachusetts held a plebiscite on a proposed constitution in 1778, it was the first election of this kind—a popular vote on a fundamental (or any) law—in the modern world. Other states followed, New Hampshire first. A new version of popular sovereignty was on the move. It faltered, however, at two key moments. In Philadelphia, the framers of the proposed US constitution chose ratifying conventions, rather than a popular vote, deliberately keeping fundamental law-making closer to elite control. Moreover, the provision they made for constitutional amendments allows an amendment to proceed entirely through Congress and state legislatures—through ordinary government, that is, rather than a special act of mobilized sovereignty. The US constitution is thus a halfway house, or maybe a three-fifths house, deeply inflected by popular constitutional sovereignty, but not quite committed to it.

Many, and soon enough most, states required popular votes to amend their constitutions, often by simple majorities. (Many still do it this way, though the importance of state constitutions is diminished by the big brother of the federal constitution.) This makes it especially pungent that the Confederate states almost uniformly avoided submitting their secession and their revised (Confederate) constitutions to the popular vote. (Virginia, Georgia, and Texas are partial exceptions, but Georgia did it after the fact, Virginia’s vote resulted in the state’s splitting and the creation of West Virginia as a Union state, and Texans voted on the secession measure but not the new constitution.) Seen in light of democratic sovereignty, the Confederacy was born in a series of coups d’etat.

What about the US Constitution? Tuck takes his title from a vivid image of Thomas Hobbes, intended to illustrate the difference between sovereignty and government. When a sovereign is asleep, his ministers are not, collectively, the sovereign. Their job is to carry out the orders he issued at naptime. The same is true, Hobbes argued, if the sovereign is a prisoner of his enemies; he remains sovereign, his word the source of law, even if he cannot act. (This argument was salient in mid-seventeenth century England, when Charles I was imprisoned by his Parliament.) The difficulty of amending our imperfectly democratic constitution means that, between amendments, the American popular sovereign sleeps for a very long time. Perhaps it is even imprisoned behind the bars of a constitution that was submitted for (quasi-)democratic authorization, but was designed by men who mistrusted democracy. If we are a republic, not a democracy, it is because our sovereign is in jail.

What does this view mean for interpreting the Constitution? Legal theorists tend to fixate on this question, often taking their cues from what the courts are doing. A benefit of Tuck’s approach is that he treats the Constitution in terms of democratic political theory, rather than judicial interpretation. This shifts the emphasis. The point of the constitution is indeed in its origins, but the point is not what it “meant” originally, but where its authority originates: in the citizenry acting as sovereign lawmaker. Tuck argues that the best way to take this is to say that the Constitution remains in effect as long as the people have not mobilized to repeal it. And that means that, in effect, it is being constantly re-authorized (or perhaps, as Yale Law scholar Akhil Amar has argued, it was re-authorized at the last time the document was amended). Conventional originalism fails, not simply because it cannot maintain the distinction between law and politics, but for a more basic reason: It fails to understand the Constitution as the product of a very special kind of political lawmaking, the only kind that is, in fact, democracy for the modern world, rather than updates of the ancien regime’s consultative government.

Tuck’s comments on constitutional interpretation are brief and do not break new ground relative to Amar or Bruce Ackerman, whose account of the Constitution in his multi-volume series We the People centers on “moments” of popular mobilization that put new political principles into effect, including the New Deal and the Civil Rights era. It would take another book to parse the difficulties that a democracy-oriented account of the Constitution confronts, given how old and often gnomic the document is and how seldom and indirectly it permits “We the People” to speak. For that, readers will have to turn to the law professors who take democracy as their starting point and ask what it requires of government, including judicial interpretation, rather than the other way around.

Tuck’s contribution is to restore the place of constitution-making within a broader case for the specialness, and difficulty, of democratic self-rule. The special thing about a constitution is not that it should save us from ourselves—any kind of government can hurt us, as Tuck notes mordantly toward the end of the book, and checks and balances were perfectly standard for centuries before 1789. It is that, unlike any other basis of government, a constitution makes possible a democratic “We” that otherwise dissolves into diffuse ideas that rulers should be responsive to “the people” and “public opinion.” Even ordinary elections only pick representatives, who act on their own judgment in divided government. Only constitution-making achieves the old idea that, in a democracy, people live under the law they make.

The irony is that, under the Constitution that most Americans prize, the democratic sovereign is either asleep or in jail, and in practice even the most democratic judge must interpret the document like a minister of the ancien regime, trying to gauge the people’s attitudes and interests by consultation, introspection, and guesswork. (Some, notably Anthony Kennedy, seem to revel in this high-ministerial role.) Perhaps our civic religion is, as Marx wrote of all religion, the opium of (We) the People.