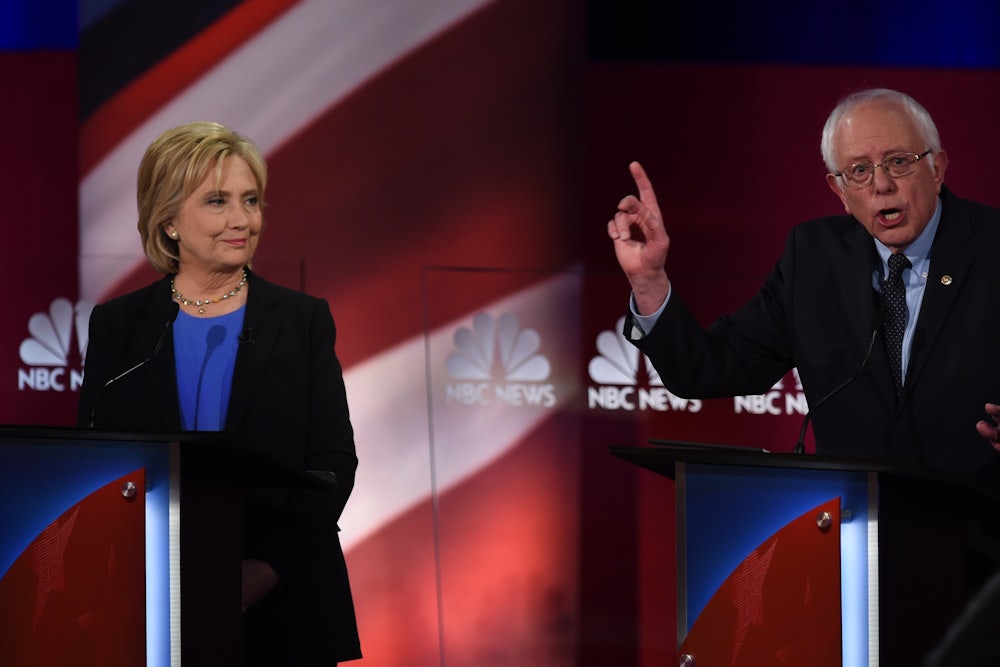

Max Weber, the great sociologist best remembered for coining the phrase “Protestant work ethic,” would have loved Sunday’s Democratic debate. Leaving aside the sad and quixotic figure of Martin O’Malley, the two main contenders Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders perfectly illustrated a distinction Weber made in his classic 1919 essay “Politics as a Vocation.” In that essay, Weber distinguished between two different ethical approaches to politics, an “ethics of moral conviction” and an “ethics of responsibility.”

Sanders is promoting an “ethics of moral conviction” by calling for a “political revolution” seeking to overthrow the deeply corrupting influence of big money on politics by bringing into the system a counterforce of those previously alienated, including the poor and the young. Clinton embodies the “ethics of responsibility” by arguing that her presidency won’t be about remaking the world but trying to preserve and build on the achievements of previous Democrats, including Obama.

The great difficulty Sanders faces is that given the reality of the American political system (with its divided government that has many veto points) and also the particular realities of the current era (with an intensification of political polarization making it difficult to pass ambitious legislation through a hostile Congress and Senate), it is very hard to see how a “political revolution” could work.

The differences between Sanders and Clinton were acutely visible when they debated the issue of health care. “Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards,” Weber wrote. That’s an almost perfect description of how Clinton approaches politics. Clinton’s core argument was that Sanders’s call for “Medicare for all” would jeopardize all that Democrats have achieved through the decades-long strong and slow boring of hard boards that it took to get Medicare and Obamacare. “What I’m saying is really simple,” Clinton argued on stage. “This has been the fight of the Democratic Party for decades. We have the Affordable Care Act. Let’s make it work.”

As against this call for responsible stewardship, Sanders forcefully articulated his moral conviction that a better system could be achieved by a politics that tackled the corruption of big money. “Do you know why we can’t do what every ... major country on Earth is doing?” Sanders asked. “It’s because we have a campaign finance system that is corrupt, we have super PACs, we have the pharmaceutical industry pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into campaign contributions and lobbying, and the private insurance companies as well.”

Sanders has a much tougher and deeper analysis than Clinton of how fundamental America’s problems are. The question is, how plausible is his prescription of political revolution as a solution?

Slate’s Jamelle Bouie wrote one of the sharpest dissections we have of Sanders’s theory of political change and found some serious problems:

On Thursday, I argued that both Hillary Clinton and Sanders need to give plans for executive branch action, given gridlock in Congress. In response, on Twitter, some Sanders supporters said this was wrong: That Sanders—with a long career in lawmaking—could win Republican support; that Sanders would use the bully pulpit to rally voters; and that a Sanders win would necessarily bring the kind of wave that would give him votes for his policies.

But this is blind to reality. Compromise is a distant shore. The Democratic Party has moved to the left, and the Republican Party has made a sharp turn to the right, guided by two generations of conservative revolutionaries, from Newt Gingrich to the Tea Party tidal wave of 2010. If you watched the Republican and Democratic debates back to back, you’d be forgiven for thinking they described two different countries. What’s more, as demonstrated by the GOP presidential race—as well as the leadership fracas in the House of Representatives—many Republicans (57 percent, according to the Pew Research Center) reject compromise full stop. The world where Donald Trump and Ben Carson lead the GOP presidential race is not a world where Republican voters would support a Democratic president or assent to his policies.

The presidency is polarizing. When you step onto its field, you become a polarized figure.

Sanders has convincingly argued that America needs a political revolution. And with his full-throttle “ethics of moral conviction” Sanders is proving to be an inspiring leader in the push for that movement. But given the way American politics works now, electing Sanders won’t achieve that revolution, which is why many voters will stick to Clinton’s more plausible politics of responsibility.