Sharon Tate was murdered in the early hours of August 9, 1969. She was 26. Her funeral was held four days later, and by then the papers were speculating about the “ritualistic” Manson family murders at 10050 Cielo Drive and the “sex-drug” cult that might have committed them. Reports of the autopsy noted that her unborn child—she had been eight months pregnant—“had been perfectly formed,” partly to stave off any speculation stemming from her husband’s film Rosemary’s Baby. As her mother bent to kiss the closed casket, “I heard her say as plain as if she was standing beside me. ‘Mother, that’s not me,’” Doris Tate told an interviewer. “That’s what saved my sanity and that’s what gave me strength, because I do believe in life after death.”

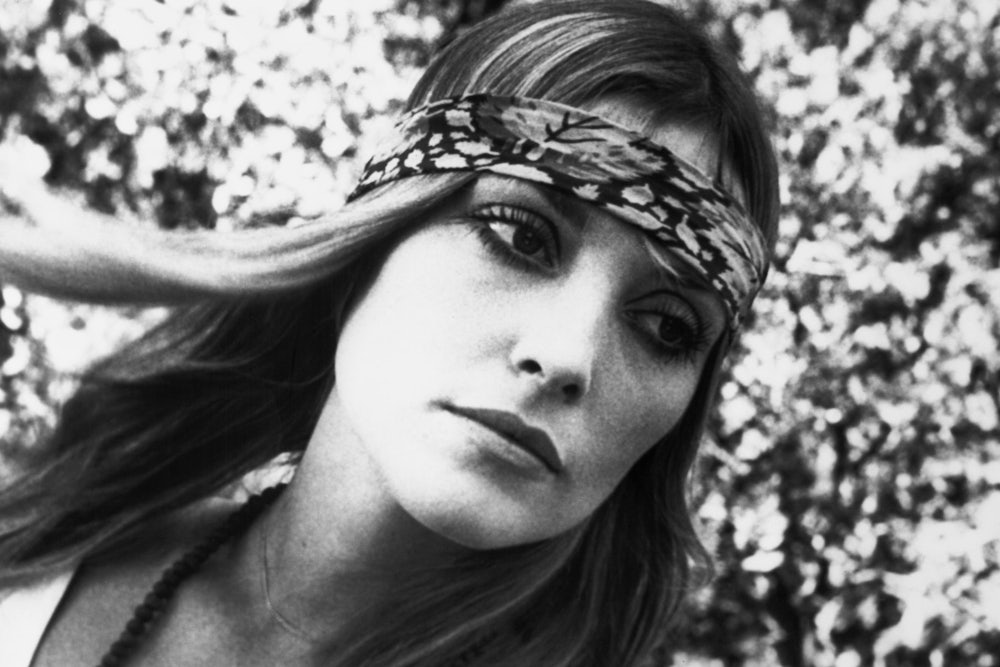

It feels cruel and unjust that a person could be reduced to a detail in the lurid story of their killers. (Any person—Tate died along with her friends Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, and Wojtek Frykowski, as well as 18-year-old Steven Parent, who had been visiting the property.) But Tate left little more to the public than her image, and her impressions on famous friends; she’d been featured in only six films. Meanwhile, her death has been packed with symbolism: the demise of the ‘60s, the loss of innocence, the suffering of women.

In his new biography, Sharon Tate: A Life, the poet, archivist, and musician Ed Sanders notes that “while there may be thousands of photos of her… Sharon Tate apparently did not keep a written and annotated trail of her life.” He avoids speculation. Without detailed diaries to draw from, or detailed recollections from many of her intimates, he has “sequenced her history, comparing various sources, as a tapestry of America during the twenty-six years she was given.” In other words, he worked with what he had: arranging her in negative, stacking details around the short path of her life.

Since the 1970s, Sanders has amassed scores of Manson archival matter, which he keeps in a barn on his property in Woodstock, NY. There’s a lot to say, and likely plenty he can’t. The book is a set of coordinates, some crucial, others of mysterious relevance, arranged as flatly as documents on a harvest table: A paragraph on Tate’s pregnancy segues into several on husband Roman Polanski’s film trajectory; a note on Tate’s marketability after Valley of the Dolls becomes a 14-page diatribe on the Robert F. Kennedy assassination. The book refuses to sensationalize Tate’s death, and avoids scavenging her memory for symbolism. But it tells us more about Sanders’s preoccupations than hers, and makes sense by his logic, which is compelling elsewhere.

Sanders wrote Sharon Tate “mainly because of the mystery that still surrounds the close of her life,” but it raises more questions than it answers: The murders might have been Manson’s attempt to spark a race war, or it might have been a contract killing, Sharon Tate having “heard too much” about something, possibly the R.F.K. assassination. Rumors abound, of satanist cult orgies, about the rape and torture of a drug dealer at Mama Cass’s house. Loose ends, as Sanders admits. And the matter of why Tate was murdered seems less interesting than the question of who she was.

Sanders is a historical figure himself, and a unicorn: a living library of 20th century counterculture—little brother of the beats, older brother to the hippies—who is not also a relic. Raised in Blue Springs, Missouri, Sanders bought and memorized Howl while in high school. “I used to shout it out to my beer-drinking buddies as we drove around the Independence courthouse square drinking Griesedick Brothers beer,” he told Steve Paul in an interview. “They ignored me. But they let me do it.” In the summer of 1958, he hitchhiked to New York City, where he studied Greek and Latin, published Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts, opened the Peace Eye Bookstore in the East Village, and formed beloved rock band The Fugs.

In early 1970, struck by the horror and intrigue surrounding the Tate-LaBianca murders, which had rippled into his social circle, he began “a frenzy of continuous day and night activity”—a deep, perilous investigation that resulted in The Family, “the first complete, authoritative account of the career of Charles Manson,” as Robert Christgau wrote in The New York Times Book Review. The Family is flamboyantly matter-of-fact, jammed with details relevant to an investigation but not a narrative—a report written in “Sanders Americanese,” as Christgau called it. Terms like “sleazo inputs” are dropped casually, weird reveals are punctuated with “oo-ee-oo,” haughty language is alloyed with hippie (“during the gobble the girl went nuts and, all in one incision, bit in twain Manson’s virility”).

Some reviewers scorned this approach—the onslaught of unprocessed detail, the conspicuous voice, and the lack of psychological insight into Manson himself. Christgau, however, called it “determinedly non-written. There is no theorizing, and no new journalism either—no fabricated immediacy, no reconstructed dialogue, no arty pace… he represents a sensibility that has pretty much rejected such devices and his book is truer and more exciting for it.” Sanders, a moralist in his own way, let the evil speak for itself. (He would later formalize some of his techniques with Investigative Poetry, the manifesto he published in 1976.) But the book offered ways of looking—it had a take—enough to pull a reader through the troughs of raw evidence, as well as the moral confidence to characterize. Manson, released from prison during the Summer of Love, was “a glib, grubby little man with a guitar scrounging for young girls using mysticism and guru babble, a time-honored tactic on the Haight.”

The Family was a substantial true crime book, written within two years of the crimes; it had an audience. It also had a point. “The Manson case engendered much confusion in the ranks of hip,” Christgau wrote. “A distressing minority… were unwilling to believe that a long-haired minstrel could also be a racist and a male supremacist who used dope and orgasm and even some variety of love to perpetuate his own murderous sadism.” Manson was the near enemy of Sanders’s counterculture. The book dispelled any notion that he was one of the good freaks.

Sanders’s intentions in Sharon Tate are more obscure. Counterculture in 2015, however you define it, is more populist than it was 45 years ago, and more willing to sympathize with the glamorous; the notion that Tate’s life and legend are worth telling is a given, but the book fails as a conventional biography. The right cultural socket could have given Sharon Tate the vitality it lacks. It would be ham-handed to impose a feminist message on her life, but the misogynistic culture she lived in (of which Manson’s extremism was an offshoot) is as good a key as any for considering her inner life. We know who she was supposed to be—who her body suggested she was—and a little about how she felt about it. But we still lack a strong sense of Sharon.

Tate’s posthumous mythology follows easily from her living reputation: reporters and colleagues remarked on her capacity for suffering as if it were a feature of her beauty, and of course it was. Sanders cites a 1988 book called Fallen Angels: The Glamorous Lives and Tragic Deaths of Hollywood’s Doomed Beauties, which reported, against her friends’ recollections, that Tate had been considering a starring role in The Story of O. You can detect a flush of pathetic sadism in contemporary accounts of her life, pleasure in both causing pain and deriving pity. “I haven’t got two cents worth of talent. All I’ve got is a body,” she read at her screen test for Valley of the Dolls. “She was perfect,” noted author Jacqueline Susann. Her co-star Patty Duke later wrote scathingly of director Mark Robson, “who used humiliation for effect,” and had singled out Tate for abuse—he “continually treated her like an imbecile, which she was definitely not, and she was very attuned and sensitive to that treatment.” Robson reportedly told Polanski, “That’s a great girl you’re living with. Few actresses have her kind of vulnerability.”

Tate reportedly said in private that she disliked both the book and the script. She was shy—“Leslie Caron invited me to a party and I was thinking: What can I say to people that would be interesting?”—but not silent. Her quotations, where Sanders includes them, are lucid and insightful: “We have a good arrangement,” she was quoted by Peter Evans. “Roman lies to me and I pretend to believe him.” She was aware of, and ambivalent about the question of her objectification. (“They see me as a dolly on a trampoline,” she said; her role in Don’t Make Waves reportedly inspired Malibu Barbie.) She was an ordinary person in an extraordinary milieu, and, like Sanders, she lived at a cultural crossroads that must have seemed both thrilling and terrifying: Raised Catholic, in a strict but loving military family, she came into herself just as the sixties began to swing. Tate had a sense of adventure; she might have craved monogamy, but she tried to adapt. “I wish I had the tolerance to let everybody have complete freedom,” Evans quoted her. “To be able to take a man home and make love and enjoy it without some lurking puritanical guilt interrupting the pleasure… Mentally it’s what I want, but emotionally it is more difficult to take.”

For a different biographer, Sharon Tate could be a friend. No one could solve the mystery of her inner life, but one could demonstrate an interest, which alone could enliven a book—some desire to understand, or relate to her. The Family’s ironic distance was warranted, but here the gulf between writer and subject feels awkward. Sanders seems to resist stepping in where he doesn’t feel he can, or should, hold forth, and this feels respectful, but frustrating—at worst a cop out, when he abandons her world for the borderlands of his interests. His organizational logic is sometimes inscrutable, with details plunked in as if by bingo blower (why, again, are we reading about Nike-Hercules missiles?). The result is that Tate fails to rise as a sensibility.

Sharon Tate: A Life is a decent project, dutiful and worthy of acknowledgment; as a read, it has moments, just not coherence. It also seems to predict its own failure, which is ethical, in a way, and honest—the only true outcome of a resurrection attempt. “Here is my tracing of the life and times of an American actress, cut off so cruelly from her husband, child, family, friends, and future films by the so far untraceable mechanisms of Fate and Evil,” Sanders writes in the foreword. By the afterword he concedes, “As for the true motive that caused Manson to send his marauders into the house on Cielo Drive, we may never know… and no loose ends can prevent our sense of outrage and anger for the horrible injustice perpetrated upon Sharon Tate and her friends.” The senseless violence of Tate’s death superseded her; at least Ed nails that senselessness.