Arriving in Russia as an American student at the end of the Cold War, during the first years of Boris Yeltsin’s presidency, life revolved around food. As it was for every Soviet citizen, it became the same for me: Where to get it, how to get it, and how to pay for it?

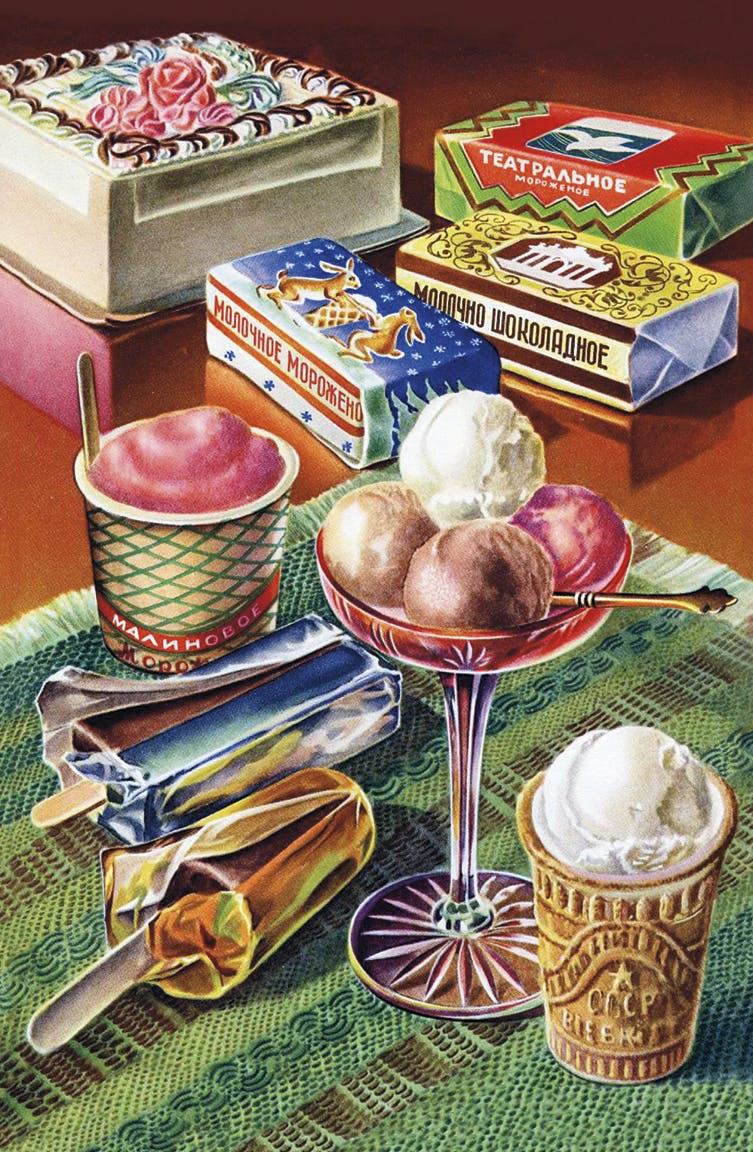

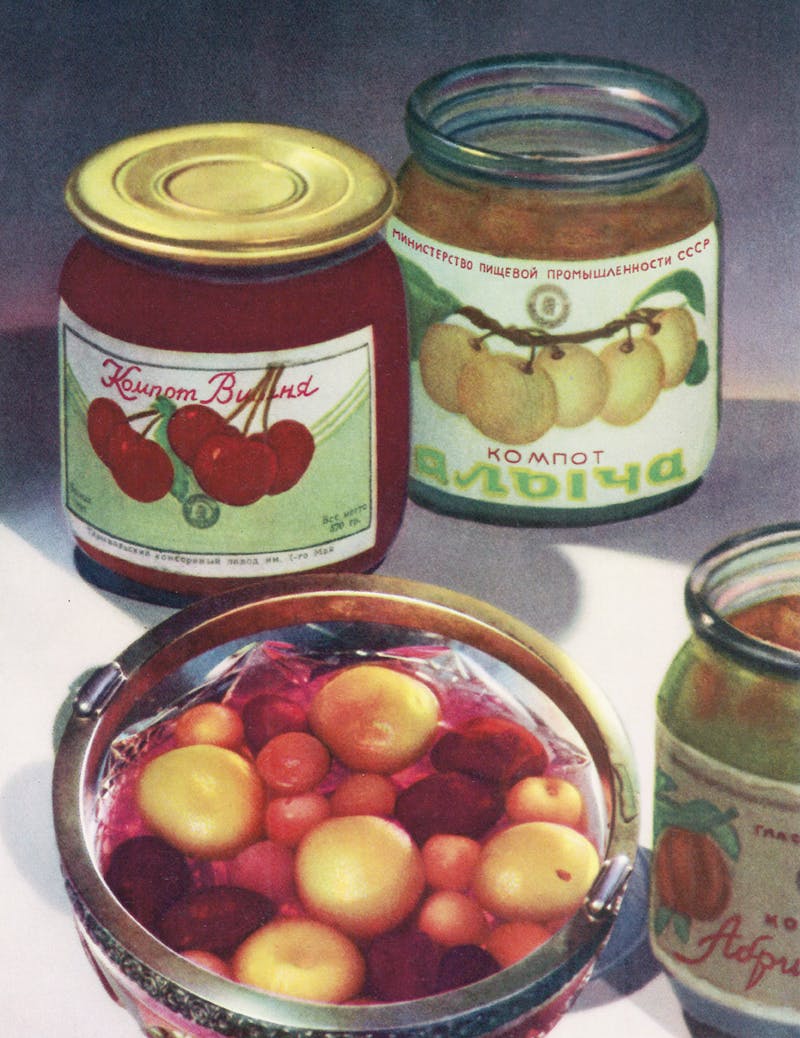

In the CCCP Cook Book, Olga and Pavel Syutkin showcase

the bounty of Soviet cuisine through the lens of social realism. Many of the images

from the book are from menus for Intourist, the Soviet travel agency begun by

Stalin in 1929, which managed foreign travel and tourism in the country. The

book also includes images and recipes for the proletariat—how to cook up what

ever might become available for the rest of the narod who were forced to

queue for hours, or ration their meals. As the authors acknowledge, “Soviet

cookery books were designed to convey a sense of abundance and endless variety.

In reality, however, things were not so rosy and their illusion of a ‘socialist

heaven’ was easily shattered.”

As a foreigner I had valuta—hard

currency, American dollars. My options were basically the same as party elite, since I had the authority to walk into a hard currency supermarket. But the food

there was imported from Finland—it was incredibly expensive and far beyond my

means, leaving me in the hunt for sustenance with everybody else in the local ruble

economy.

Like other Soviet citizens, I became used to going out with several small string bags known as avoska in the event that a car full of apples, cabbage, vegetable oil, or tea bags, had simply “fallen off a truck.” The first winter after the demise of the USSR, there was no fruit to be had, until suddenly in March there was a gold rush of bananas in Moscow, and citizens who were unaccustomed to the fresh tropical fruit left peels in piles in the gutters.

Traveling around the former USSR gave me access to the Intourist hotels and restaurants. The opening question from a customer to the wait staff in any restaurant, assuming you were allowed to sit down, was simple: “What do you have?” There was no use wasting one’s time looking at a menu, most of what was described was unavailable. A scowling state-employed waiter might bring a Stolichny Salat (mayonnaise, pickles, tiny chopped potatoes, maybe a spring of parsley) or if I was very lucky, Gribni Julienne, creamy baked mushrooms to slather on a slice of black bread.

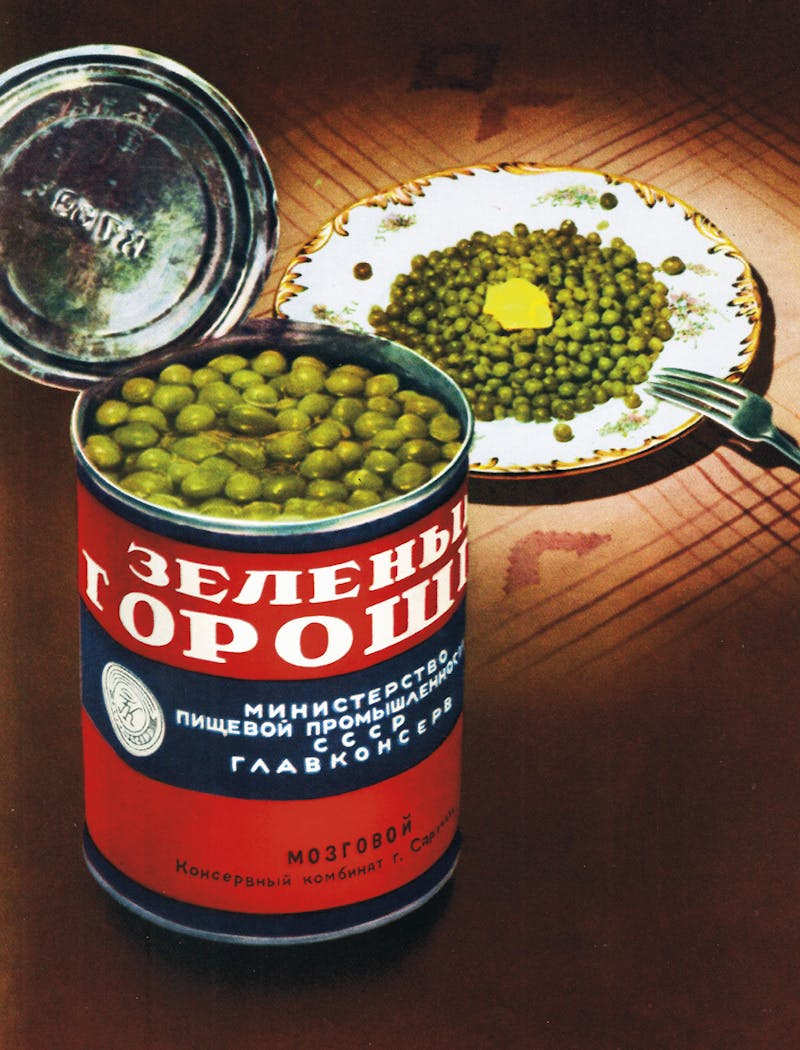

I experienced the twilight of Soviet cuisine. Olga and Pavel Syutkin explain that the golden age began with reforms of the 1930s that brought technology from the West, as well as food distribution systems, which led to an increase in variety of recipes, the establishment of Soviet flavors, and even the publication of cookbooks with quality paper stock. However not all food was available all the time. Any “Capital” Salat, in pre-revolutionary times was known as the holiday dish Olivier Salat and it originally called for capers, grouse, crayfish tails and black caviar. By the end of the 1930s, capers had disappeared and grouse and crayfish were hard to come by, so a chef in Moscow recreated it by replacing grouse with chicken, tinned peas for capers, and carrots replaced crayfish. Stolichny Salat became one of the standards of Soviet cuisine.

I would visit my Russian friends as often

as they would invite me to simple meals of borscht and fried potatoes, or Okroshka,

translated by the Syutkins as “mystery ingredients,” in short, any food you can

find cut into small cubes. Frankfurters, cucumbers, radishes, hard-boiled eggs,

with obligatory smetana (a type of

sour cream), could all be included, and during a food shortage Okroshka became

a popular meal.

The authors of the CCCP Cook Book

are food historians, and the

recipes they include come with historical anecdotes that contextualize the

dish. Many Soviet cookbooks were written for the public-catering industry,

and recipes would have three columns to specify portion size depending on the

target consumer: restaurants for the elite, cafés for the middle class, and canteens that fed workers and educational

institutions.

The recipes in the third column were the least nutritious, using less butter and meat. For instance for studded beef, a single serving contained 125g of meat in the first column, 100g in the second and only 70g in the third. The shortfall was made up with increased amounts of pasta, rice or potatoes. In this respect, the “culinary heaven” for workers was so modest it barely met the nutritional minimum.

Soviet aspics are dishes designed to evoke aristocratic banquets for the common man: Pikeperch patties with mayonnaise sauce and jelly and stuffed venison fillet set in a gelatin aspic are literal towers to Soviet imagination and no doubt, the state’s culinary achievement.

MOSKOVSKY BORSCHT

For 9-12 servings:

3 litres meat

or vegetable stock

2 tbsp butter

2 small onions

1 carrot

3 medium-sized beets

2 large tomatoes (or 3-4 tinned tomatoes or 3 tbsp tomato purée)

Juice from half a lemon

2 tsp sugar

2 medium-sized potatoes

2 or 3 bay leaves

3 or 4 cloves

Garlic, salt, and pepper to taste

One small chilli pepper and a selection of fresh herbs (dill, parsley,

coriander, etc.)

Sugar and vinegar to taste sour cream or horseradish to serve

Make a meat or vegetable stock and prepare the rest of the ingredients while it is cooking. Melt the butter in a deep pan and add the onions and carrots, both sliced into thin strips. Cook until lightly brown, then add the beet, sliced in the same way. Add the grated tomatoes or tomato purée, lemon juice and sugar and stir well.

When the mixture comes to the boil, cover and simmer for 40 minutes, stirring occasionally to prevent sticking. When the stock is ready, add the finely diced potatoes and 5-7 minutes later add the cooked vegetable mixture. It is imperative at this point not to let the soup boil—keep the heat low and simmer for 3 minutes.

Add the bay leaves, salt and pepper and chili pepper if you want a more spicy soup, along with sugar or vinegar to taste. If you made meat stock, add the finely sliced meat. Add the sliced garlic and fresh herbs if required then remove the soup from the heat and allow it to cool for 30 minutes. Serve with sour cream. If you use vegetable stock and sauté the vegetables in vegetable oil, the borscht can be served cold with sour cream or horseradish. Borscht reaches the peak of its flavor the next day, so it is often left to sit for a day or two in the fridge.

*

This article is a part of No One’s Watching Week, the time of the year when the readers are away, and your tireless editors have run amok. For this week only, Atlas Obscura, New Republic, Popular Mechanics, Pacific Standard, The Paris Review, and Mental Floss will be swapping content that may be too out there for any other week in 2015. This article originally appeared on the New Republic.