In 1921, in a Munich beer hall, newly appointed Nazi party leader Adolf Hitler gave a Christmas speech to an excited crowd.

According to undercover police observers, 4,000 supporters cheered when Hitler condemned “the cowardly Jews for breaking the world-liberator on the cross” and swore “not to rest until the Jews…lay shattered on the ground.” Later, the crowd sang holiday carols and nationalist hymns around a Christmas tree. Working-class attendees received charitable gifts.

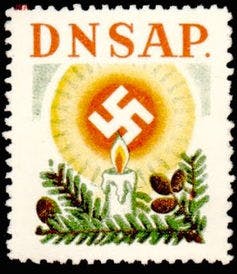

For Germans in the 1920s and 1930s, this combination of familiar holiday observance, nationalist propaganda and anti-Semitism was hardly unusual. As the Nazi party grew in size and scope—and eventually took power in 1933—committed propagandists worked to further “Nazify” Christmas. Redefining familiar traditions and designing new symbols and rituals, they hoped to channel the main tenets of National Socialism through the popular holiday.

Given state control of public life, it’s not surprising that Nazi officials were successful in promoting and propagating their version of Christmas through repeated radio broadcasts and news articles.

But under any totalitarian regime, there can be a wide disparity between public and private life, between the rituals of the city square and those of the home. In my research, I was interested in how Nazi symbols and rituals penetrated private, family festivities—away from the gaze of party leaders.

While some Germans did resist the heavy-handed, politicized appropriation of Germany’s favorite holiday, many actually embraced a Nazified holiday that evoked the family’s place in the “racial state,” free of Jews and other outsiders.

Redefining Christmas

One of the most striking features of private celebration in the Nazi period was the redefinition of Christmas as a neo-pagan, Nordic celebration. Rather on focus on the holiday’s religious origins, the Nazi version celebrated the supposed heritage of the Aryan race, the label Nazis gave to “racially acceptable” members of the German racial state.

According to Nazi intellectuals, cherished holiday traditions drew on winter solstice rituals practiced by “Germanic” tribes before the arrival of Christianity. Lighting candles on the Christmas tree, for example, recalled pagan desires for the “return of light” after the shortest day of the year.

Scholars have called attention to the manipulative function of these and other invented traditions. But that’s no reason to assume they were unpopular. Since the 1860s, German historians, theologians and popular writers had argued that German holiday observances were holdovers from pre-Christian pagan rituals and popular folk superstitions.

So because these ideas and traditions had a lengthy history, Nazi propagandists were able to easily cast Christmas as a celebration of pagan German nationalism. A vast state apparatus (centered in the Nazi Ministry for Propaganda and Enlightenment) ensured that a Nazified holiday dominated public space and celebration in the Third Reich.

But two aspects of the Nazi version of Christmas were relatively new.

First, because Nazi ideologues saw organized religion as an enemy of the totalitarian state, propagandists sought to deemphasize—or eliminate altogether—the Christian aspects of the holiday. Official celebrations might mention a supreme being, but they more prominently featured solstice and “light” rituals that supposedly captured the holiday’s pagan origins.

Second, as Hitler’s 1921 speech suggests, Nazi celebration evoked racial purity and anti-Semitism. Before the Nazis took power in 1933, ugly and open attacks on German Jews typified holiday propaganda.

Blatant anti-Semitism more or less disappeared after 1933, as the regime sought to stabilize its control over a population tired of political strife, though Nazi celebrations still excluded those deemed “unfit” by the regime. Countless media images of invariably blond-haired, blue-eyed German families gathered around the Christmas tree helped normalize ideologies of racial purity.

Open anti-Semitism nonetheless cropped up at Christmastime. Many would boycott Jewish-owned department stores. And the front cover of a 1935 mail order Christmas catalog, which pictured a fair-haired mother wrapping Christmas presents, included a sticker assuring customers that “the department store has been taken over by an Aryan!”

It’s a small, almost banal example. But it speaks volumes. In Nazi Germany, even shopping for a gift could naturalize anti-Semitism and reinforce the “social death” of Jews in the Third Reich.

The message was clear: only “Aryans” could participate in the celebration.

Taking the ‘Christ’ out of Christmas

According to National Socialist theorists, women—particularly mothers—were crucial for strengthening the bonds between private life and the “new spirit” of the German racial state.

Everyday acts of celebration—wrapping presents, decorating the home, cooking “German” holiday foods and organizing family celebrations—were linked to a cult of sentimental “Nordic” nationalism.

Propagandists proclaimed that as “priestess” and “protector of house and hearth,” the German mother could use Christmas to “bring the spirit of the German home back to life.” The holiday issues of women’s magazines, Nazified Christmas books and Nazi carols tinged conventional family customs with the ideology of the regime.

This sort of ideological manipulation took everyday forms. Mothers and children were encouraged to make homemade decorations shaped like “Odin’s Sun Wheel” and bake holiday cookies shaped like a loop (a fertility symbol). The ritual of lighting candles on the Christmas tree was said to create an atmosphere of “pagan demon magic” that would subsume the Star of Bethlehem and the birth of Jesus in feelings of “Germanness.”

Family singing epitomized the porous boundaries between private and official forms of celebration.

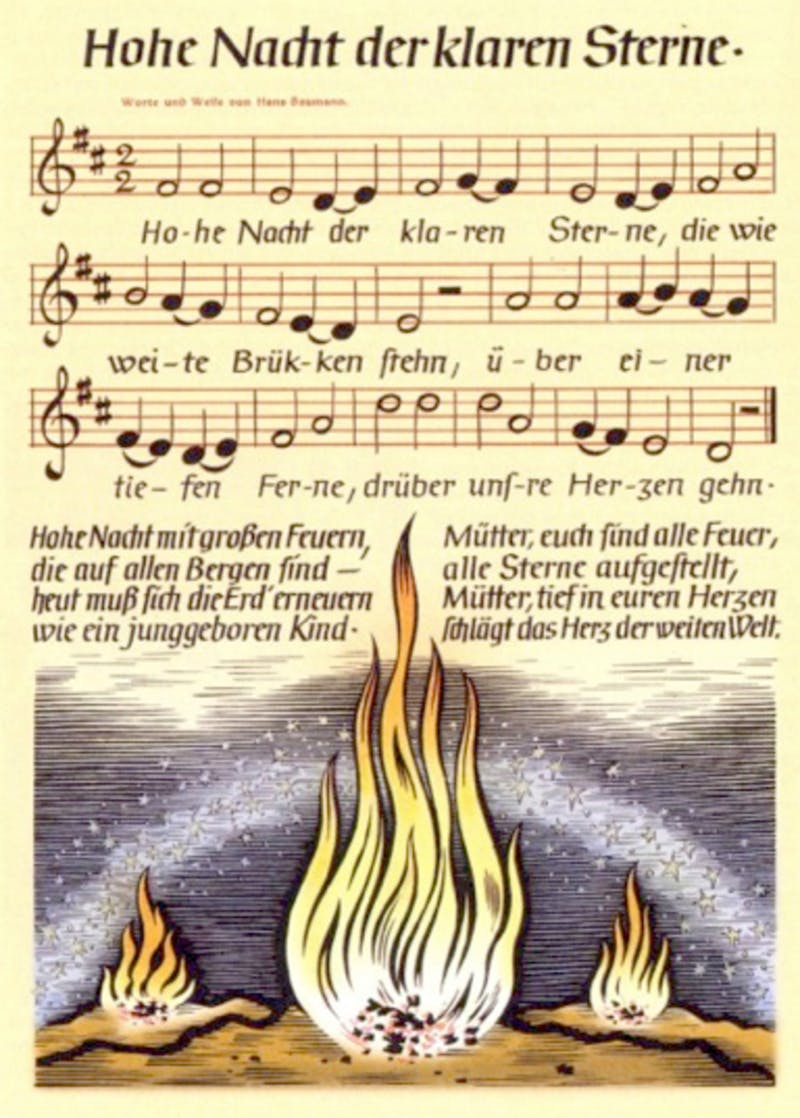

Propagandists tirelessly promoted numerous Nazified Christmas songs, which replaced Christian themes with the regime’s racial ideologies. Exalted Night of the Clear Stars, the most famous Nazi carol, was reprinted in Nazi songbooks, broadcast in radio programs, performed at countless public celebrations—and sung at home.

Indeed, Exalted Night became so familiar that it could still be sung in the 1950s as part of an ordinary family holiday (and, apparently, as part of some public performances today!).

While the song’s melody mimics a traditional carol, the lyrics deny the Christian origins of the holiday. Verses of stars, light and an eternal mother suggest a world redeemed through faith in National Socialism—not Jesus.

Conflict or consensus among the German public?

We’ll never know exactly how many German families sang Exalted Night or baked Christmas cookies shaped like a Germanic sun wheel. But we do have some records of the popular response to the Nazi holiday, mostly from official sources.

For example, the “activity reports” of the National Socialist Women’s League (NSF) show that the redefinition of Christmas created some disagreement among members. NSF files note that tensions flared when propagandists pressed too hard to sideline religious observance, leading to “much doubt and discontent.”

Religious traditions often clashed with ideological goals: was it acceptable for “convinced National Socialists” to celebrate Christmas with Christian carols and nativity plays? How could Nazi believers observe a Nazi holiday when stores mostly sold conventional holiday goods and rarely stocked Nazi Christmas books?

Meanwhile, German clergymen openly resisted Nazi attempts to take Christ out of Christmas. In Düsseldorf, clergymen used Christmas to encourage women to join their respective women’s clubs. Catholic clergy threatened to excommunicate women who joined the NSF. Elsewhere, women of faith boycotted NSF Christmas parties and charity drives.

Still, such dissent never really challenged the main tenets of the Nazi holiday.

Reports on public opinion compiled by the Nazi secret police often commented on the popularity of Nazi Christmas festivities. Well into the Second World War, when looming defeat increasingly discredited the Nazi holiday, the secret police reported that complaints about official policies dissolved in an overall “Christmas mood.”

Despite conflicts over Christianity, many Germans accepted the Nazification of Christmas. The return to colorful and enjoyable pagan “Germanic” traditions promised to revitalize family celebration. Not least, observing a Nazified holiday symbolized racial purity and national belonging. “Aryans” could celebrate German Christmas. Jews could not.

The Nazification of family celebration thus revealed the paradoxical and contested terrain of private life in the Third Reich. The apparently banal, everyday decision to sing a particular Christmas carol, or bake a holiday cookie, became either an act of political dissent or an expression of support for national socialism.

![]() This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.