What does it mean to “read” a photograph? To see an image is to perceive it optically, to read an image is something more. It suggests an understanding of what is pictured and perhaps a grasp of the context in which it was taken. It also implies the photographer recognizes the visual grammars through which the image will be received, or read, by a viewer. But what happens when the usual grammar breaks down? Is the picture then unreadable? Or might it become a new form of photography with its own unique grammar, its own legibility, and its own new narratives to divulge?

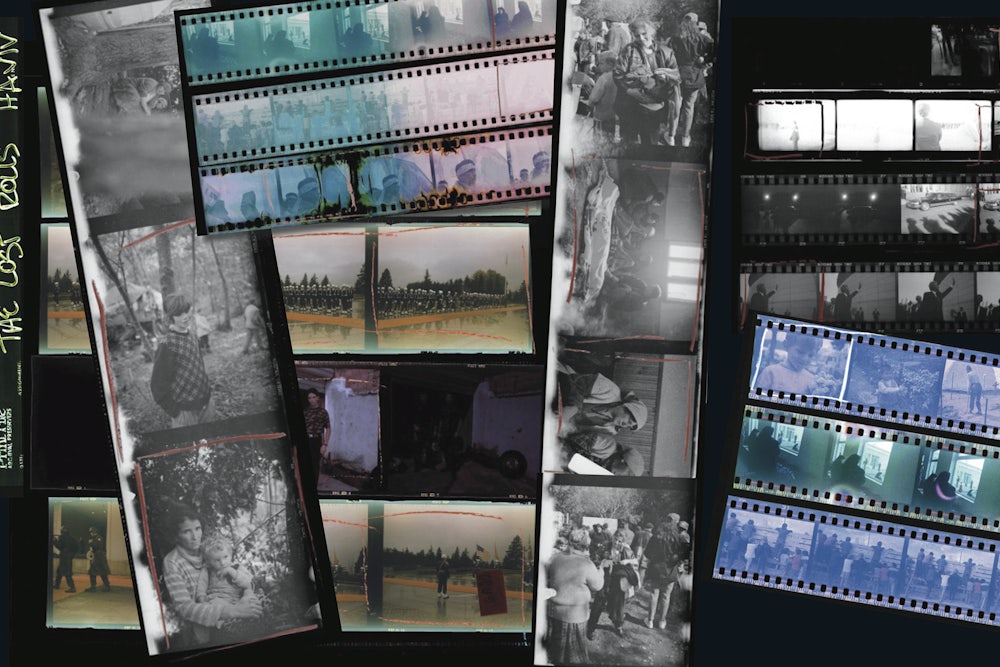

Photojournalist Ron Haviv’s new book The Lost Rolls: 1988-2012 is a project that forces these questions to the foreground. Having discovered rolls of undeveloped film from his years covering conflicts in Afghanistan, Bosnia, the West Bank, and Rwanda, among other travels, Haviv had the experience of being reacquainted with the past, in some cases decades later, when he processed the film in 2015. The photos, like a Rorschach test, call forth factual details, personal anecdotes, and pensive reflections; in at least one case, the Rorschach draws up a blank. “I can try to piece together where I was, but not what I was doing or why I was there,” writes Haviv.

This project, situated squarely in the digital era, is an ode to the past—to a time when undeveloped rolls of film might lay buried amidst papers in a desk or orphaned in a kitchen drawer among worn-down pencils, cap-less pens, and dried-out rubber bands. It is an ode to an experience many of us may have had coming across a stray roll of unprocessed Kodak film. It is perhaps also a lament to the passing of that experience, as fewer and fewer photographers—whether professionals, hobbyists, or cellphone camera users—shoot on film. The Lost Rolls offers a penetrating look at the relationship between photography and memory.

A photograph is an instant, captured visually, removed from the continuum of time. A memory is similar: We can’t remember everything we’ve ever experienced; certain instants, events, and details stand out. We remove them from the continuum of time, and, at least metaphorically, “tuck” them away. Remembrance is the act of revisiting, perhaps even reanimating a past experience at a future point. And often it is visual in nature.

Photography has long been linked with memory. In an 1859 article in The Atlantic, Oliver Wendell Holmes describes the daguerreotype as “the mirror with a memory.” Marcel Proust wove a similar comparison into Remembrance of Things Past, referring to “mental photographs,” “snapshots of memory,” and “that inner darkroom” where we “develop” experiences. Toward the end of the novel, the narrator laments that too often one’s “past is encumbered with numerable ‘negatives’ which remain useless because the intelligence has not ‘developed’ them.” Nearly a century later, Haviv plays with this idea, exploring what might have been lost had his negatives never been developed, as well as what is gained in the act of processing them belatedly.

Proust, a quintessential author of memory, investigated “the vast structure of recollection,” where remembrance, at times, can be so crystalline that the rememberer very nearly re-inhabits the past in all its colors, scents, sounds, and textures. But for Proust’s narrator these are rare moments; more common are the memories that remind us of past experiences, which we can’t revisit in complete detail—because memory, of course, is fragile, fallible, and pliable. It changes over time and, like long forgotten film stock, it degrades. Sometimes its edges become frayed and the colors bleached—names lost, places forgotten, dates obscured.

As a tangible form that, in ways, acts like a memory, the photograph would seem a helpful tool for reminding us of prior occurrences. Everyone has likely had the experience of looking at an image from one’s own past and being “taken back” to the event pictured, reminded of aspects or details—the photo helps jog the memory. Italo Calvino adds a withering, postmodern spin in his short story, “The Adventure of a Photographer:”

When spring comes, the city’s inhabitants, by the hundreds of thousands, go out on Sundays with leather cases over their shoulders. And they photograph one another. They come back as happy as hunters with bulging game bags; they spend days waiting, with sweet anxiety, to see the developed pictures … It is only when they have the photos before their eyes that they seem to take tangible possession of the day they spent, only then that the mountain stream, the movement of the child with his pail, the glint of the sun on the wife’s legs take on the irrevocability of what has been and can no longer be doubted. Everything else can drown in the unreliable shadow of memory.

Not only is the photograph a helpful tool for recalling the past, it is also the means by which the past is made real. Photographs provide evidence of experiences; they substantiate the past, turning it into a concrete “possession,” as Calvino notes—small, flat, rectangular instances of time that live inside albums.

Haviv’s photos are also tangible artifacts, documents of a lived past. But when Calvino’s days of “sweet anxiety” turn into years for Haviv, the moments of history are sometimes lost irrevocably; visual evidence can’t always call up the past. When he looks at his own images, Haviv’s memories waver: Some are strong, specific scenarios, and others are mere veneers where the original context of the image has been lost. But this doesn’t lead to a drowning in “the unreliable shadow of memory,” as Calvino has it. Haviv takes the opportunity to float, bask, and swim in this unstable realm.

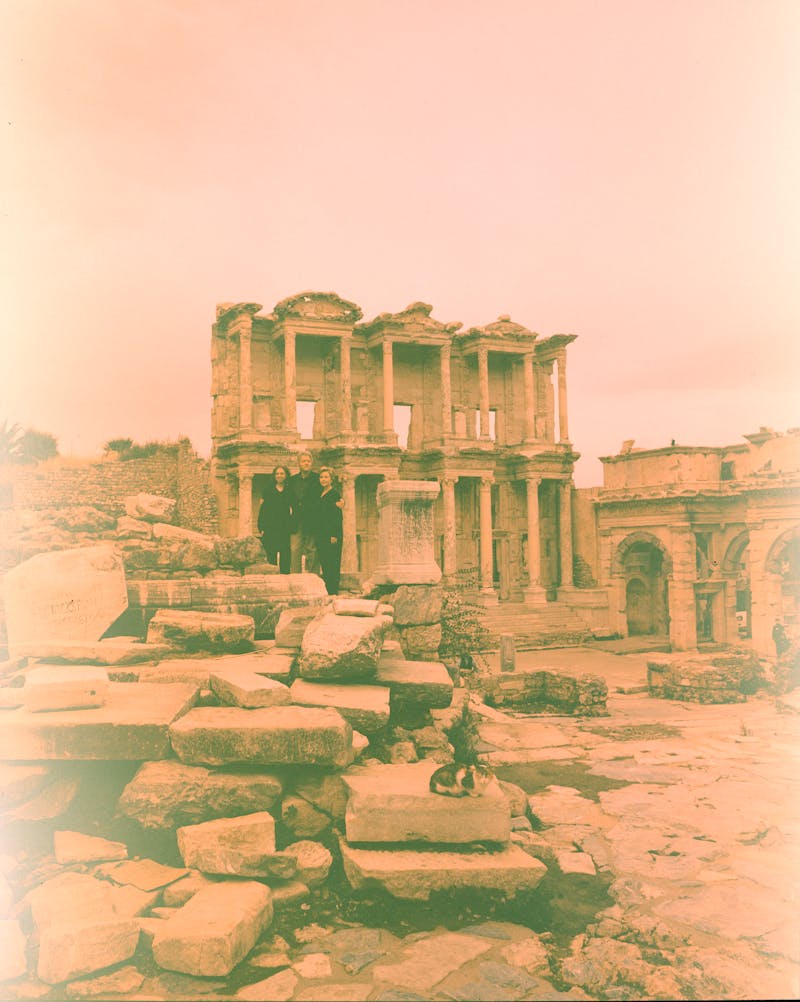

Many of the photographs in The Lost Rolls were shot as photojournalistic documents, but in the book they appear in an artistic context, stripped of their journalistic information. Several of the images were chosen for this project precisely because they have—with time, wear, and destruction—aged into something that visually begs us to consider them with a fine arts sensibility, as with the cover image for this book that looks almost as if flames of live fire lick its edges.

The curated pages of this book, a miniaturized gallery space, emphasize the liminal quality of Haviv’s photos—the space between journalism and art, past and present, memory and loss. We may not even be sure how to read these photos because they occupy and simultaneously reject the various categories into which one tries to place them. As a result, we’re forced to think about the visual grammars or implicit expectations we conventionally default to when looking at imagery.

Haviv literalizes this condition in the “broken” grammar of some of his vignettes, the written reflections that appear alongside a handful of the images and that read at times like fragmented thoughts, indicative of the fragmenting of memory. “I began to wonder what else was I misremembering,” he writes. In turn, we could view the “destruction” of the various warped images as paralleling the gaps in memory, but this destruction has also rendered beautiful new forms.

Even the images of the well-preserved negatives perform in new ways in this ahistorical, disjointed series, as a new way of reading grows from the lost memories no longer tethered to Haviv’s found images. Now the “fiery” cover photo links with at least three others in the book: a bus engulfed in flames; Yitzhak Rabin’s coffin, lying in state above a mass of flickering candles; and a sleeping man in a restaurant, where a light leak in the film has created, again, a flame-like aura creeping up the banquette. The images shot originally as journalistic documents are not dispossessed of that role and are consequently imbued with a richly layered history. In The Lost Rolls, we can read each historical image in a newly reimagined history, one where aesthetic themes allow unexpected connections, from the West Bank to Northern Ireland to Jerusalem to Mexico.

We are also, here, given special access to the unfiltered, less polished productions of a renowned photographer’s eye, to see history through the themes that compelled Haviv, consciously or not, whether political, personal, social, or aesthetic. Even Haviv’s choice of images for this book gives us privileged insight into his special way of seeing the world and thinking about the status of images as they change, conceptually and physically, over time.

A photograph, a frozen instant of time, can never tell, or show, the whole story. This is why scholars have long noted that photos encourage speculation, and also why an accurate caption is so essential to a photojournalistic image. In giving little textual information directly alongside the photos, Haviv openly reminds us of this aspect of photography. Haviv’s pictures invite, even embrace, such speculation, allowing the viewer to participate in the exploration of the past: Who is this dark-haired, Madonna-like woman wrapped in a blanket? She looks quietly at peace though also poignantly sad. And why is one t-shirt laid open when all the other clothing is balled up? These hypnotic tableaus sometimes take us out of the past and place us in the present, as we focus on the gorgeous details of damaged film, the new imagery that overlays the old.

In the end, The Lost Rolls is a fascinating manifestation of an inherent fact of photography: Photos can never resurrect the past, as much as they are sometimes considered agents of memory, but they can powerfully compel a viewer to look, and more so, to read the image, both its past and its present. Such is the afterlife of photographs. And so we swim adrift in these images, in a river of history out of order and context, but oh so beautifully beguiling.

This excerpt has been adapted with permission from the introduction to The Lost Rolls: 1988-2012 by Ron Haviv.