At long last, modern Turkey has been depicted in comic book form.

The work has a modest title, Dare to Disappoint, but its ambitions are large. Its creator, Özge Samancı, has produced a Künstlerroman that also recreates life in Turkey in the 1980s and early 90s, a time when the country’s secular heritage was enforced with a severity that has come under scrutiny in the era of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Here in Turkey, where her book is topping bestseller lists, Samancı has become the year’s most inspiring figure among comic artists, and a subject of intrigue for Turkish magazines, newspapers, and budding artists.

“I was amazed with the power of lived stories,” Samancı, now an assistant professor at Northwestern University’s film department, told me, discussing the roots of the book some 15 years ago in notebooks filled with sketches that she gave as gifts to friends. “It was helping others to recall their forgotten memories. Since then I wanted to make a graphic memoir.”

In Turkey, the politics is personal. Samancı’s story kicks off in 1981 in the coastal city of Izmir, the artist’s birthplace. She is six; her older sister Pelin is starting at the school just opposite their apartment. The scene takes place a few months after the bloody coup of September 12, 1980, marking a years-long ascendance of the military in matters both small and large, public and private. Samancı watches her sister waving from a school corridor through a set of binoculars, longing to be out there. She grows obsessed with the school uniforms, the ultimate symbol of the state’s reach into Turkish society in the 1980s.

One of Dare to Disappoint’s chapters is devoted to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey’s modernizing founder. “You are Ataturk’s little soldiers,” Samancı’s teacher tells her class. Reading from a textbook, all students are asked to shout out, “Every Turk is born a soldier!” She starts seeing symbols of Turkish nationalism everywhere—from the post office to calendars, from the school garden to the first page of all course books. The official culture, which Samancı absorbs like a sponge at school, is juxtaposed with the narrative of her mother’s younger brother Nihat, a socialist who informs her that she is being brainwashed. “The mentality at schools is like the mentality in the military,” he says. “They want us to all be the same.”

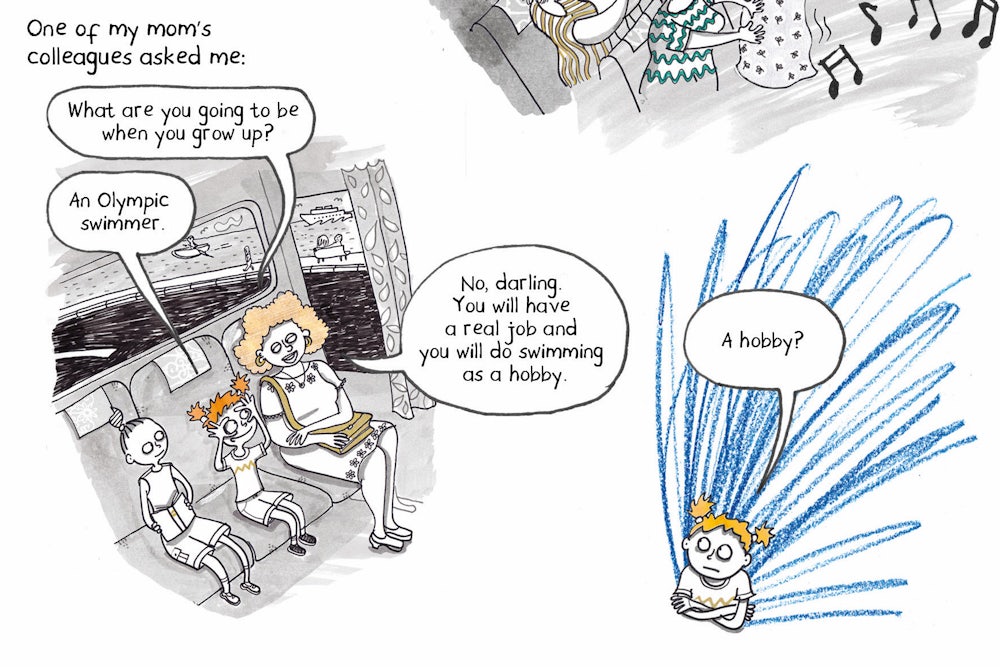

That conformity extended to other areas of her life. As a girl, Samancı felt she was pushed into traditional Turkish norms. Dare to Disappoint presents her as a trouble-maker trapped between her family’s expectations and what she wants to be. “Maybe I am still somewhat trapped,” she told me. “I did not want to live the standard life, buy a house and a car and get a job. ... I wanted to dedicate myself to a cause and live a life worthy of living. But I did not want to upset my parents, their friends, their relatives, and so on.”

Samancı’s personal liberation, her culmination as an artist, inspired the title of her debut. “I might have dared to disappoint at one level and became an artist even though I studied mathematics,” she said. “But that’s not the end of the story. Life keeps offering us opportunities to dare to disappoint. It gets more challenging.”

A few years her junior, I remember the 1980s in Turkey in much the same way Samancı does. It was a time when the state consolidated itself, but there were also upheavals caused by the economic liberalization of the country.

In her book, Samancı’s parents, for example, are both civil servants. Their income allows them to lead a modest life, protected from the graffiti-covered walls of the outside world that speak of the tensions between Turkey’s communists and nationalists. But her parents are kept back by Turkey’s economic liberalization in the second half of 1980s. While their wages stagnate, the family’s entrepreneurially minded friends and neighbors start making fortunes. One of Samancı’s drawings depicts the son of a family friend equipped with a walkman, a fancy backpack, a handsome allowance, foreign magazines, and imported soccer shoes. Meanwhile, the Samancı sisters wear clothes sewed by their mom, and attend public schools.

The influence of the West can also be seen at the top. We learn about the crucial role the American TV series Dallas played for Turks, how we were fascinated with the lifestyle in Dallas and “elected a new prime minister”—Turgut Ozal—“whose dream was to transform Turkey into a little U.S.”

But those changes didn’t reach into Samancı’s school life. In the book, the Samancı sisters spend their childhoods studying all the time, with their uncle worrying they will get permanent brain damage. Thanks to Turkey’s exams culture, the young Samancı becomes increasingly obsessed with test scores while having little self-confidence, often envious of those coming from more privileged backgrounds.

She goes to a boarding school for high school, the first time she has lived apart from her parents, and these scenes offer subtle insights into the cultural antagonisms that haunt Turkey today. In her class most boys come from conservative families and are practicing Muslims; meanwhile, Samancı and her girlfriends mostly come from secular backgrounds. Conservative boys view them as promiscuous; girls, in turn, find their male friends extremely dull.

Pushed into depression by the dysfunctional Turkish education system, Samancı looks for inspiration in an unlikely figure: Jacques Cousteau, the French explorer, conservationist, filmmaker, and author. Cousteau first enters her world through an undersea documentary shown on Turkey’s state broadcaster, and Samancı immediately places his picture on her bedroom wall.

But more than Cousteau, she desires to please her parents. She ends up attending Turkey’s most prestigious college, the American-founded Bosphorus University, where she enrolls in the mathematics program. Before long she regrets the decision.

At the end of Dare to Disappoint, she is 23 and full of enthusiasm for an artistic career. Today Samancı is 40; in the intervening years she drew obsessively, around eight hours a day. The financial support came from her sister, while Samancı also tutored high school students to help pay the rent. She drew for the weekly humor magazine Leman, but soon realized she needed a real job. She was surprised to be hired as a teaching assistant at Istanbul’s Bilgi University, in the visual communication design department, where her career as a comic artist was acknowledged for the first time.

“Working in the design department and making comics for the humor magazine, I understood how I was happiest while working with images,” she said. “After that everything I did involved images.” She started a web comic, Ordinary Things, and produced interactive installations. “It took so much effort for me to arrive here,” she said.

Shaping

the book’s narrative took two years. She started writing it in 2010, when she was a visiting fellow at the

University of California, Berkeley. She rewrote the story six times,

thought of giving up, then somehow managed to finish it. After completing two chapters she found an agent, and in

less than a month’s time Dare to Disappoint was sold to the publisher

Farrar, Straus & Giroux. “The day of the sale I was so shocked that I

forgot my keys and locked myself out,” she laughed.

When Samancı first starting making autobiographical sketches for her friends, she thought that she had invented a new genre. But while that may have been naive, books like Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle have breathed new life into autobiography, showing the different ways in which it can be approached.

“I wrote and drew my story exactly as I remember,” Samancı told me. “I did not include any fictional elements. Even the radio in the story is our family radio. I found an image of our old Sony radio and drew from it. I am obsessed with showing the exact image that I remember. I spent hours to finding photos of many other props such as our black and white TV, carpets, stoves.”

She added, “That said, what we see in the book is coming from my memory. We all know human memory distorts events, but friends and family who read the earlier drafts would have told me if there was a distortion.”

In the future, Samancı wants to produce a book that mixes lived experience with fiction. “Comics artist Lynda Barry has called it autobiofictionography,” she said. “There is a way of mixing autobiography with fiction in an ethical way.”

There is a touch of Marjane Satrapi, of Persepolis fame, in Samancı’s work, but just a touch. Her Turkey is a patriarchal society, doubly oppressed by the forces of militarism and nationalism, and is presented to us through the perspective of a prospective feminist. But thanks to its era-traversing narrative, Dare to Disappoint’s politics is subtler in scope. Samancı’s younger self encounters constant obstacles; she shows how the education system turned independent-minded youngsters of our generation into test-obsessed monsters. But in Samancı’s telling nothing seems more oppressive than middle-class family expectations. And despite social pressures, which abound in Turkey’s society, the young artist in Dare to Disappoint is allowed to pursue her dreams—and is lucky enough to discover what those dreams are.