In writing about Star Wars, certain conservatives love to do a twist on the old adage that “one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter.” Luke Skywalker and the other rebels against the Galactic Empire are usually seen as the good guys of Star Wars series but by now there is a venerable right-wing literature celebrating Darth Vader and the Emperor Palpatine as enlightened rulers fighting to bring order to the universe. Building on earlier essays by other writers in The Weekly Standard and The Washington Post, a blogger called Comfortably Smug has extended the argument by labeling Luke Skywalker a terrorist:

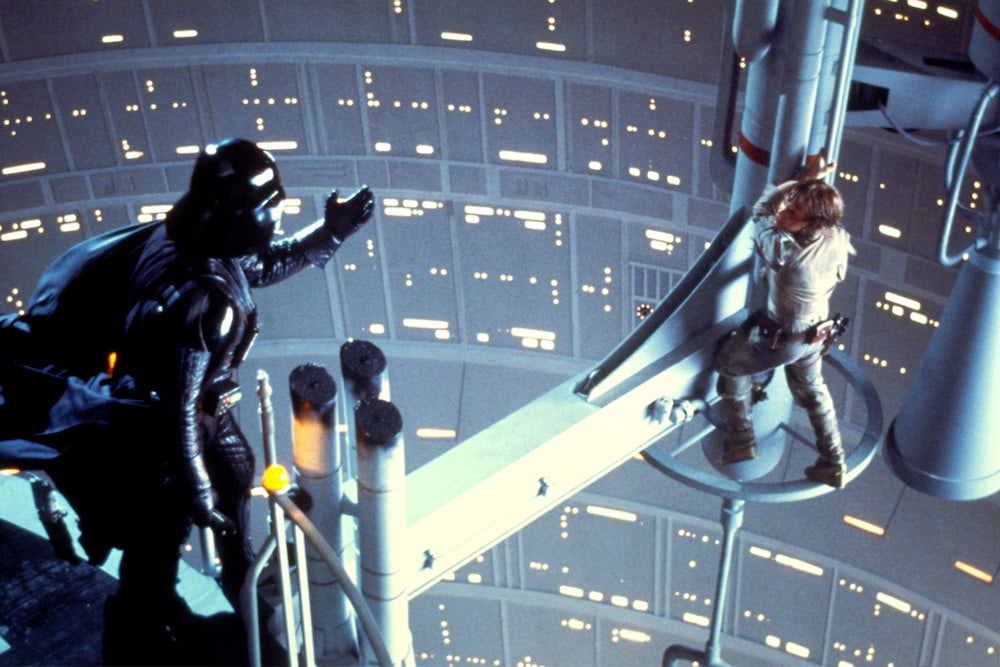

[T]he Star Wars films are actually the story of the radicalization of Luke Skywalker. From introducing him to us in A New Hope (as a simple farm boy gazing into the Tatooine sunset), to his eventual transformation into the radicalized insurgent of Return of the Jedi (as one who sets his own father’s corpse on fire and celebrates the successful bombing of the Death Star), each film in the original trilogy is another step in Luke’s descent into terrorism.

In effect, Comfortably Smug is arguing that Jedi equals jihad.

Such arguments only work if you ignore the manifest evidence that the Empire is evil, notably the war crime of destroying the planet of Alderaan, a clear act of genocide. Yet there’s an element of truth in these interpretations: In shaping the first Star Wars trilogy, George Lucas was influenced by the anti-colonialist politics of the 1960s and 1970s; he has acknowledged that the struggles between the Ewoks, the gentle woodland species that fights the empire, and the Galactic Empire was partially modeled on the battles between the Viet Cong and the American army. He was also influenced by the anti-imperialist literature of that time—in particular Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune. But what conservative analysts don’t realize is that both Herbert and Lucas belong to a particularly American tradition of sympathy for anti-imperialist forces, and Dune itself was a product of a time when America saw jihad as a valuable tool in the struggle against a rival empire, the Soviet Union.

A Cold War allegory, Dune shows how complex the theme of jihad was. Its impact on Star Wars can be seen in everything from the everything from the desert landscape of Luke’s home planet Tatooine (which calls to mind Arrakis) to the larger backdrop of a universe where high tech and magic merge in a struggle against a Galactic Empire. In the world of Dune, the freedom-loving House Atreides (a stand-in for the United States) is in competition with the house of Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (whose name has obvious Russian connotations) for control of the resource rich desert planet of Arrakis. In order to win the struggle, the Paul Atreides forms an alliance with the religious natives of Arrakis, and together they wage a jihad in the form of guerrilla war against the Harkonnens. The jihad would eventually backfire and lead to the terrible spread of religious fanaticism throughout the galaxy.

This is partly why Dune is a remarkable novel: It prefigured the strategic dilemmas America would face in the Middle East, where alliance with anti-communist jihadis in the Cold War led to terrible blowback. As such, Dune used science fiction to offer a complex analysis of the world. The first Star Wars trilogy is somewhat simpler than Dune, with a more black-and-white view of the world. Still, in the trilogy there is a genuine awareness of the problem with empire and the way imperial dominance leads to resistance. The conservatives who want to use Star Wars to celebrate empire reveal that their understanding of history is even more simplistic than a movie franchise aimed at children.