This is the second story in a two-part series on AdvoServ, a for-profit company that operates a network of facilities for the disabled in several states. The first story can be found here.

One winter

day nearly eight years ago, Lori Kennedy-Shields dashed off an email to her

son’s private boarding school before starting the 90-minute drive through

Florida’s rural midsection, to a lake-dimpled stretch of small towns northwest of

Orlando. Carlton Palms Educational Center was an unusual school, but so was her

son. Though Adam was 23 and nearly six-and-a-half feet tall, his brain

resembled that of a toddler. Impulsive and playful, he did inappropriate things—like belting out songs at the top of his lungs in public or swatting people

on the head to get their attention. He could dress himself and brush his teeth,

but he needed constant supervision. Diagnosed with severe autism at age two,

Adam could parrot phrases, yet he often struggled to speak, unable to string

together words.

Carlton Palms’s specialty was teenagers and adults with serious intellectual and developmental disabilities like his. Its modular classrooms and living quarters were wedged between orange groves outside the quaint town of Mount Dora. Adam had lived there for seven years, ever since his Tampa-area public school system had acknowledged that it was failing to teach him. Over that time, the school district and state agencies had paid more than $1 million for Adam’s tuition and care. Kennedy-Shields hoped the school would show her son how to express himself better and master basic life skills, like how to cross the street safely. Her dreams for his future were modest; she wanted him to be able to hold down a simple job one day, perhaps washing dishes or folding laundry.

With Kennedy-Shields that day were her husband, Tom, and Adam’s younger brother and sister, Noah and Cara. They had packed their Chevy Suburban with new toys, clothes, and treats for Adam, and they were looking forward to watching him gleefully descend upon the bounty. But as they neared Carlton Palms, Kennedy-Shields’s cellphone rang. A supervisor had only just read Kennedy-Shields’s email, and the school was not expecting them. Kennedy-Shields, who had recently clashed with administrators over Adam’s medications, made it clear that she was not turning around.

Less than a half-hour later, she and her family sat in a conference room on the Carlton Palms campus, waiting for Adam. He usually greeted his mother with bright eyes and a snippet of a pop song when his own words wouldn’t come. But when Adam appeared in the doorway, he was silent. Kennedy-Shields was stunned by his appearance. His hair looked greasy and unwashed, and his clothes hung off his thin frame. Typically exuberant, Adam was expressionless. Oblivious to his visitors and the gifts they had brought for him, he shuffled in, staring ahead.

As Kennedy-Shields studied him, her eyes settled on a bright red, raw sore the size of a quarter on his wrist. “What’s that?” she asked a member of the staff, pointing. The employee casually explained that someone must have put Adam’s restraints on wrong.

Restraints? Kennedy-Shields knew Carlton Palms workers could hold down residents in a dangerous situation—such as, she’d thought, if they tried to run into traffic. But no one said anything like that had happened with Adam. What would leave such a mark? She demanded to see Carlton Palms’s executive director, Tom Shea.

When the longtime ambassador for the school strode into the conference room, she immediately challenged him. “What’s going on?” she asked. She pressed him to explain the wound on Adam’s arm, his ill-fitting clothes and his deadened expression. Shea grew angry and refused to discuss it, getting up from the chair he’d barely settled into. Kennedy-Shields, a petite woman with round brown eyes and waves of jet-black hair, put herself between him and the door.

What Kennedy-Shields did not know during that visit was that Adam had been restrained before—not once, but hundreds of times. He had been bound after scratching and hitting and kicking, and after what started as simple defiance. After chucking a toy or dinnerware in frustration. After ignoring an order to clean up.

She had no inkling, either, that a paper trail locked away in Carlton Palms’s files showed Adam’s behavior worsening as workers used increasingly harsh methods to control him. She knew nothing of the searing accounts of abuse and neglect that had for decades trailed the school’s parent company, a for-profit chain of group homes and schools called AdvoServ. (Read our story about abuse at AdvoServ, and how the company has bullied regulators and evaded accountability.)

Each year, nearly 20,000 youngsters with severe disabilities like Adam’s are sent to live at special education schools at public expense. Federal law gives parents that option when local public school districts can’t or won’t accommodate their children. But there’s little to guarantee that such vulnerable students—some are unable to speak for themselves—receive safe or humane treatment. As Kennedy-Shields would learn, standards for such programs are so loose, monitoring so inconsistent, and penalties so rare that some have escaped serious repercussions even for repeated or egregious lapses.

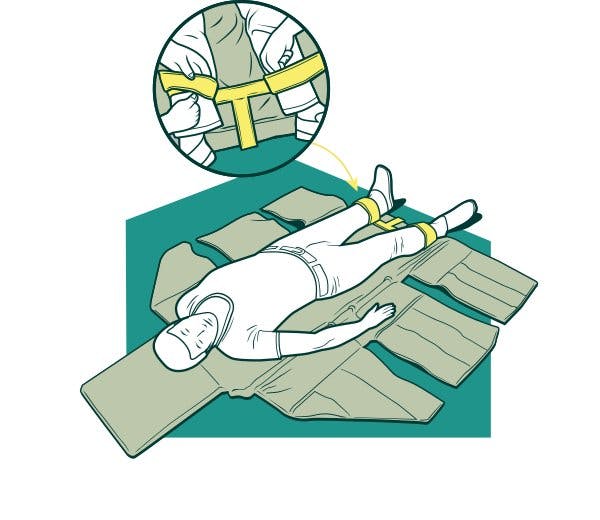

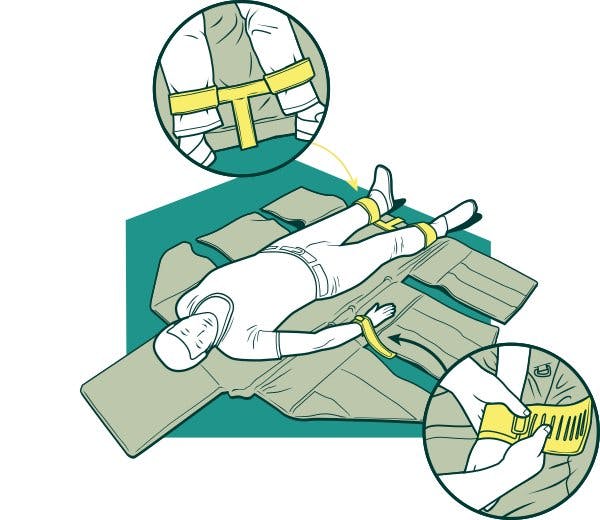

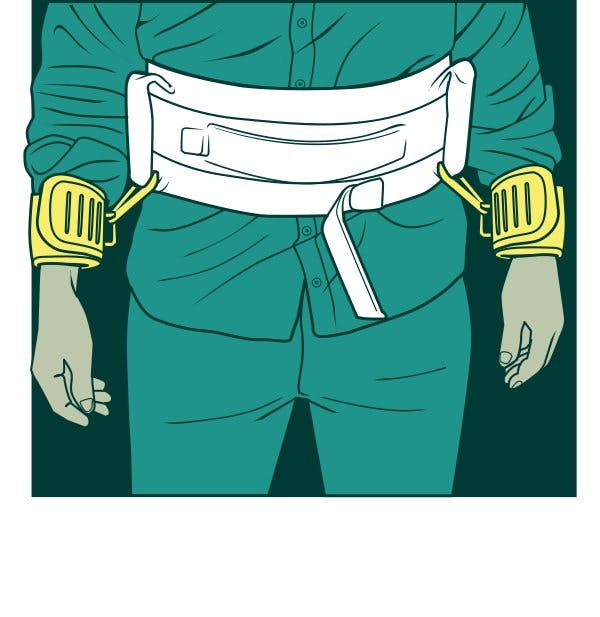

AdvoServ cares for 700 disabled children and adults at 77 facilities in three states, with Carlton Palms by far its largest campus. State officials and advocates for the disabled have long known of its aggressive use of restraints—holds or devices that limit residents’ ability to move their heads, torsos, arms, or legs. In particular, the company became known for embracing so-called mechanical restraints, such as straps on chairs or beds, wrist cuffs, or “wrap mats” that resemble full-body straitjackets. Most providers stopped using such measures long ago, after concluding they were risky and often ineffective over the long-term.

Other than Carlton Palms, just two group homes in Florida reported using such devices at all in the first quarter of 2015. Those two homes, which together have about half as many residents as Carlton Palms, used them 88 times over a five-month period. Carlton Palms used them 4,107 times.

In less than five years, Carlton Palms has put its residents in mechanical restraints 28,000 times—a number that made California-based behavior analyst Jeffery Hayden gasp.

“What I’m envisioning,” said Hayden, a consultant for residential care programs, “is just a place full of terror.”

AdvoServ defended its methods, telling ProPublica it takes on residents with disabilities and behavior challenges that other providers can’t handle and that it uses restraints only as a last resort, “when there is imminent danger.” Terry Page, the company’s clinical director, cited two studies that found mechanical restraints are safer than manual restraints. (Both studies were published nearly 30 years ago.)

In 2011, Kennedy-Shields sued Carlton Palms, alleging that the restraints Adam endured—involving equipment that harked back to asylums of eras past—violated Florida law, scarring him physically and emotionally.

To this claim, AdvoServ officials responded that any restraints used were necessary and performed with Kennedy-Shields’s consent, in accordance with the law. Reached this summer at his home, Shea, now retired, declined to answer questions for this story.

“We disagree with the claims made by Adam’s mother, especially considering Adam remained in our care with the permission of his family for [seven] years,” company officials said in a statement. “But because the case is in active litigation it is inappropriate and irresponsible for anyone, including ProPublica, to attempt to litigate the case prematurely, and with only half the story.”

It would be years after Kennedy-Shields’s tense final visit to Carlton Palms before she learned the truth about Adam’s time there.

Back in 2008, in the cramped conference room that unseasonably warm winter day, she only knew something was deeply wrong.

“What,” she pleaded to Shea, “did you do to my son?”

Adam had seemed to fall from the sky into Kennedy-Shields’s arms in 1985.

She and her husband had been devastated when their plans to adopt another boy were derailed at the last minute. Not long afterward, a friend happened to step into a hospital near her office to buy a candy bar and began chatting with the nurses, who were calling adoption agencies because a new mother had just decided to give up her baby. The friend told them about Kennedy-Shields and her husband. Three days later, Adam went home with them.

Kennedy-Shields was 25, and life was full of possibility. She had landed a job as a medical lab technician and married her college sweetheart. They had bought their first home. A doctor had told her that she would never be able to bear children, but now she and her husband were starting a family.

Before he turned two, Adam developed some unusual habits—like rolling shoelaces between his fingers over and over again. He often didn’t respond when adults spoke to him. Concerned, his pediatrician sent the family to a psychiatrist when Adam was 27 months old. Less than a minute into the appointment, the psychiatrist began using the word “autism.”

Kennedy-Shields felt little emotion that day as she listened to the doctor. She didn’t know much about autism, a mysterious disorder that was diagnosed far more rarely then. She checked out a mountain of books from the University of South Florida library near her home. The books she read were full of depressing and now-discredited theories.

Later that week, as Kennedy-Shields was working the night shift, she began to weep. Hopes for Adam’s future that had barely begun to take shape were already dashed. He would never go to college or get married; he would never have a career or children of his own. “It’s a death of a sort,” she says now. “It’s a death of a dream.”

She grieved that night and over the weeks that followed. And then, suddenly, her perspective shifted. She saw Adam was happy. He loved to play with his blocks and listen to music. He found satisfaction in simple things. “That was really my salvation,” she says. “It didn’t matter that I had had these dreams for him. He was content.”

Determined to give Adam the best life she could, she tried a host of special services and therapy. She enrolled him in a pioneering early childhood autism program at a nearby university. When her first marriage ended and she remarried, she traveled to North Carolina with her new husband—a physician—so Adam could try an experimental therapy that involved sound. Kennedy-Shields and her husband later took Adam to have the electrical activity in his brain mapped. He underwent metabolic testing. In the end, Kennedy-Shields wasn’t sure any of it made a difference, but she never stopped seeking help.

When Adam was eight, Kennedy-Shields and her husband adopted another boy. Four years later, she found herself unexpectedly pregnant with a girl. Her days were simultaneously draining and fulfilling. She had stopped working when Adam was five. For years she served as president of the Hillsborough County, Florida, chapter of the National Autism Society, but she eventually gave that up, too, to concentrate on her children.

The family moved several times and tried not to let Adam’s disability limit them. They ate in restaurants, took long car rides, and vacationed far from home, even taking Adam hiking in the Smoky Mountains. Every weekend, he’d ride a roller coaster twice at Busch Gardens. It always calmed him.

Adam smiled often, but sometimes he shrank from others’ touch. He would rock back and forth, chewing absently on the soft pad at the base of his thumb. He put things in his mouth that weren’t food—like crayons, blocks, and Play-Doh—though he didn’t typically swallow them. But in many ways, Adam was the easiest of Kennedy-Shields’s three children to raise. “He doesn’t talk back,” she says. “He doesn’t do anything that could be construed as mean.”

Kennedy-Shields did worry that strangers would misunderstand Adam. She avoided taking him to quiet places, like movie theaters, because of his singing. And as he grew bigger, his habits of slapping people to get their attention and playing chase-me games made her wary of public spaces.

When he hit puberty and experienced the rush of hormones that comes with it, Adam began acting out during his short visits with his adoptive father, Kent Fields. (Adam took his last name.) Fields says Adam slapped and bit himself and banged his head. He put his hand through the wall. One time, Fields intervened when he saw Adam running toward his toddler stepsister with a raised baseball bat. To keep Adam from hurting himself, Fields would wrap his arms and legs around the boy as he flailed. Adam didn’t have the same problems at his mother’s house, and his teachers never reported incidents like that.

Adam’s schooling remained vexing, too. One afternoon when he was in middle school, as Kennedy-Shields waited on the bottom step of the school bus, Adam hit the bus driver on the head to say goodbye. Startled, the driver slapped Adam—hard—with the back of her hand.

Kennedy-Shields complained. The driver took early retirement, but the school district never apologized.

Kennedy-Shields also feared Adam wasn’t learning much in the classrooms where he sat all day with other disabled students. In middle school, his teacher spent long stretches outside, smoking cigarettes. When Adam got to high school, Kennedy-Shields says she found out his purported instructor worked with other students outside his classroom for most of the day. One classmate walked out the door and managed to cross a four-lane highway by himself—three times.

After Kennedy-Shields’s complaints, the school district transferred Adam to a public school for special education kids. Not long after, Adam took off, too—passing through an unlocked front gate and walking a few blocks to Boy Scout Road, the busy thoroughfare that leads to Tampa International Airport. The school’s principal jumped in her car and went after him. “So that was the end of that for me,” Kennedy-Shields says. “I thought, OK, this is it, I’m done with Hillsborough County.”

She knew she was running out of time to find Adam a good school. He was 16, and while his peers were looking ahead to graduation, he had six years before he aged out of public education. Kennedy-Shields had hoped that by this point, he’d have acquired basic vocational skills, but that wasn’t happening. Nothing seemed to be happening, except the ticking of the clock.

Someone at an autism society meeting told her about Carlton Palms’s reputation for working with kids like Adam. She toured its lakefront campus, taking along a therapist from a university-affiliated autism center. The school had opened 13 years earlier, in 1987. When she visited, it had roughly 75 residents, adults and children—most in their teens—with similar disabilities. The campus had a playground and a basketball court, and its small classrooms sat off a quiet, dead-end road. There were no four-lane highways in sight. Though she had done everything she could for him, Kennedy-Shields knew Adam had a great deal to learn before he could live in the world as an adult. She did a cursory check online. Nothing she found raised any alarms.

She wanted the school district to acknowledge it was failing to educate Adam and to cover his tuition at Carlton Palms. When district officials resisted, she hired an attorney. That was on a Thursday. By the following Monday, the school district had backed down.

Kennedy-Shields went with Shea, Carlton Palms’s director, to observe Adam in his class in Tampa. Shea was personable, charismatic, and confident in what he was pitching, she says. He agreed the boy would be a good fit for the school.

Before Adam left for Carlton Palms, Kennedy-Shields filled out a mountain of paperwork. One form said that in case of “severe behavior problems,” staff members might use emergency measures that involved “manually holding an individual” or “physically restraining an individual with restraints approved for such purpose, applied until the person is calm.” Wanting to keep Adam safe, she signed it without hesitation.

Kennedy-Shields says the school informed her that, to help Adam make the transition to life at Carlton Palms, he shouldn’t have any contact with his family for at least two months. The idea left her unsettled, but she told herself that she needed to set aside her misgivings. Her friends had told her to think about what was best for Adam in the long-term. Ultimately, her husband drove Adam to Carlton Palms, because Kennedy-Shields feared she couldn’t do it. “I thought I would turn around and come home,” she says.

Adam’s admissions forms noted that he was in good physical health, on no medication, slept well, and had a good appetite. Under “patient chief complaint,” it listed acne.

Weeks passed. Kennedy-Shields’s house in northern Tampa was strangely quiet without Adam, whose voice she longed to hear. She’d rarely left him; they’d only once spent a few days apart. When she called each day to check on him, Carlton Palms staff assured her that her son was fine. She felt relieved that perhaps she had finally found a way to help him take a few more steps toward independence.

Unbeknownst to Kennedy-Shields, the pastoral setting at Carlton Palms belied a more turbulent history.

AdvoServ traced its roots to the Au Clair School in Delaware. According to a 1979 series in the Wilmington News-Journal, staffers said children with autism were being beaten as part of their treatment. Three years before Adam set foot in Carlton Palms, a New York Times story detailed more problems at the company’s Delaware facilities, including state inspectors’ discovery of children in trailers smelling of urine and feces and workers’ description of suspicious injuries.

Throughout the 2000s, complaints about AdvoServ facilities streamed in to child and adult protective service agencies. The homes’ reliance on mechanical restraints resulted in a trail of injuries. AdvoServ’s leaders defended the measures as necessary to protect residents from harming themselves or others, but some residents and their families recall needlessly violent takedowns, followed by extended periods of confinement. Donna Salvato said this happened repeatedly to her brother, Jimmy Mullins, when he lived at an AdvoServ home in New Jersey in the late 2000s.

“They’d tie my whole body in the mat,” said Mullins, now 42, who is developmentally disabled and prone to explosive rage. “The thing they’d tie my wrists on would hurt me really bad.”

Many homes for the disabled had reduced or phased out mechanical restraints by then. Federal law and professional standards had restricted their use in health care settings. Providers increasingly turned to alternatives. They trained workers to pay closer attention to medical problems that could provoke outbursts, and used positive encouragement to get residents to avoid risky behaviors.

At Carlton Palms, workers were sometimes overwhelmed. Staffing shortages could mean they worked two, or even three, eight-hour shifts in a row and monitored as many as eight residents at a time, said Jill Bass, who was a therapist at the facility for nine months in 2010. When residents acted out, workers were quick to use restraints. “Take them down, take them down,” said Bass, who left after injuring her ankle while using a manual hold to stop one patient from attacking another. “That was their way.”

Restraints were ingrained in the company’s culture, but there was more than that at work, added Glen Gandy, who worked with residents at Carlton Palms for several years. High turnover meant workers often didn’t know residents well enough to calm them, and they would turn to restraints instead, Gandy said. He was fired in 2012 after an incident in which he and other workers attempted to wrestle a thrashing resident into a wrap mat. As Gandy held the resident’s head, the man bit down on Gandy’s finger. Gandy broke the man’s jaw—accidentally, he says—getting his finger out of the man’s mouth.

AdvoServ said in a statement that the company’s turnover is “higher than we’d like” but lower than the industry average. Officials also said they have only used triple shifts “in the case of a natural disaster,” and that the company has always met staffing and training requirements.

Kennedy-Shields had little way of knowing about the abuse complaints involving Carlton Palms. Such allegations usually aren’t publicized or available to parents, especially if their child is not involved. Right after the no-contact period ended, she went to see Adam, who appeared to be doing well. “When I saw him,” she says, “he was so happy to see me.” She says she visited at least once a month and called at least once a week. She’d pack her car up with new clothes, candy, and toys and leave the bustle of Tampa, passing rolling hills and grazing cattle on the way to Mount Dora. She always called or emailed ahead, alerting staff when she planned to arrive on campus.

Employees would bring Adam to her at the main administration building, and they would visit in a conference room. If it was a weekend, when administrators weren’t there, they would go into a classroom or hang out at the swings. They’d sing to each other and have simple conversations, with Adam signaling his preferences with a word or gesture. Each fall in the first few years Adam was there, she and her family attended Carlton Palms’s family day—a festival featuring pony rides and barbecue dinners. She never saw anything that gave her pause. She later realized she didn’t see all that much—staff members usually asked her to stay in designated areas and only let her see her son’s bedroom once in seven years.

Kennedy-Shields participated in phone meetings with Carlton Palms and school district officials about Adam’s special education plan. He seemed to be making progress—at least toward the narrowly constructed targets set for him. The school told her he was completing more tasks successfully. But Kennedy-Shields had no way to check. His lack of speech and the fact that he was so far from home made it impossible for her to verify what Carlton Palms told her. And though it was paying the bill, the school district didn’t independently evaluate Adam’s academic growth.

Adam aged out of the school system in 2007 when he turned 22. But Medicaid—the government insurance program for the poor and disabled—paid for him to continue his stay at Carlton Palms as an adult.

Staffers said they would keep working to help Adam meet his goals. Yet Kennedy-Shields found herself enmeshed in a series of conflicts with Shea. The tensest interactions were over her son’s health.

Adam started taking an antipsychotic drug a few years into his stay, after Carlton Palms staff told Kennedy-Shields that her son was agitated. She balked at first, but relented, hoping it would help Adam relax. The program’s doctor would change drugs and adjust doses regularly, depending on how well the medicine seemed to be working.

Then, in 2006, she got a letter from a Medicaid psychiatrist suggesting the antipsychotic Adam was on should be monitored closely because of potentially dangerous side effects. A psychiatrist working for Carlton Palms responded that all the necessary lab work had been done, writing, “Thank you, so much, for this incredibly intrusive waste of my time.” But Kennedy-Shields began to ask more questions. Her son hadn’t been diagnosed as psychotic or bipolar. “They were always pushing it with me, and I was like, ‘I don’t think he needs this,’” Kennedy-Shields says. “There is no drug for autism.”

In 2007, she said, Shea threatened to discharge Adam if Carlton Palms couldn’t put him on Abilify—a potent antipsychotic that is sometimes prescribed for autistic patients who are irritable or lash out. As with all antipsychotics, the potential side effects were frightening—they could include diabetes, significant weight gain, and involuntary facial tics. Kennedy-Shields had grown worried that Adam’s caretakers weren’t paying close enough attention to his reactions to drugs. Once, she’d found him gasping for breath after a medication change, but staff hadn’t seemed to notice. So this time, Kennedy-Shields refused to give her consent.

A bigger blowup came soon after, when she learned that a blood test had shown that Adam was anemic, a diagnosis he had never received before. She asked the doctor who worked at Carlton Palms to find out why. Shea told her never to call the doctor again and denied the anemia, Kennedy-Shields says—though a nurse had read the full test results to her. (She says she never got an explanation, though she later surmised he simply wasn’t getting enough food.)

Noah, Adam’s brother, remembers visiting Adam and seeing his face torn up from itching and scratching after an apparent allergic reaction that had gone untreated. “It looked like a raccoon had attacked him,” Noah says. Another time, Adam took off running during a visit—and fought workers when they grabbed him—something Noah says he wishes the family had viewed as a warning sign.

By early 2008, Kennedy-Shields was fed up. She asked Adam’s support coordinator—who assisted families with Medicaid in arranging for services—what she needed to do to move Adam. A few weeks later, Kennedy-Shields discovered the raw wound on Adam’s wrist. Shea responded to her questions with rage, she says.

“I don’t have to take this shit from you,” Shea told her during their February 2008 confrontation, Kennedy-Shields says. They sat around a table in a small conference room with faux-wood paneling. Shea grabbed her son’s chair in his hands and pushed it roughly, she says, as he squeezed past and headed for the door. She jumped to her son’s defense. “Get the fuck out of my way,” he told her, she says. He is going to hit me, she thought. She stepped aside.

In court proceedings related to Kennedy-Shields’s lawsuit, Shea has denied making those comments.

Kennedy-Shields wanted to put Adam in the Suburban and take him home right away. The support coordinator urged her not to act rashly—paperwork had to be filled out, and she’d first need to set up a bedroom in her house for Adam and line up a new behavior analyst. After what had happened, they wouldn’t lay a hand on Adam, he said. He told Noah to lead Kennedy-Shields out. “I’m sure they were very scared driving home with me,” she says. “I was hysterically crying the whole way.” No one spoke during the ride.

Shea wrote a letter of dismissal for Adam, calling Kennedy-Shields uncooperative and saying she was unwilling to work with staff.

Kennedy-Shields told legal advocates for the disabled about the confrontation. Someone complained to the state about Adam’s treatment. Carlton Palms reported that it was discharging Adam “due to verbal attacks against staff, doctors etc by” an unnamed person who made “all kinds of accusations against the staff,” state records show. (The names are blacked out, but it is clearly referring to Kennedy-Shields.) Nothing came of the complaint.

After her confrontation with Shea, Kennedy-Shields spent weeks in a frenzy, rearranging her home and life to prepare for Adam’s return.

He no longer had a bedroom in her house, so the family had to redecorate his old room. They made sure big pieces of furniture, like bookcases and dressers, were bolted to the wall so he couldn’t accidentally pull them over. They fixed the locks so he couldn’t work them. They moved electronics and remote controls up high, because Adam liked to turn up the sound so loud he’d blow the speakers. They put plexiglass on the window so he wouldn’t break one with a slap, as he had before.

Kennedy-Shields called the state Agency for Persons with Disabilities, too. The agency wanted to put Adam in a group home for people with “intensive behaviors.” She refused and fought to arrange for aides and a behavior analyst to work with her son at home. Distracted one day outside the agency’s building after a heated encounter, she got into a minor car wreck after failing to look before changing lanes.

As the weeks ticked by, Kennedy-Shields worried about Adam “every minute of the day,” her husband, Tom Shields, says. “I don’t think she slept for two weeks. You could see the distress on her face worrying about it.” She’d wonder what was happening that day. She’d say over and over, “He needs to be out of there.”

Finally, one day in April, Adam arrived home in a Carlton Palms van that carried all his possessions. A bit hesitant when he first walked in the door, he soon happily roamed a house he knew well, visiting his bedroom and rummaging through kitchen cabinets like he’d never left. His brother and sister—who had been nine and five when he had left—were now 16 and 12. Kennedy-Shields hovered over Adam like she hadn’t in years, making him his favorite sandwich—a “fluffer-nutter”—and attending to his every need.

But any comfort Kennedy-Shields felt in Adam’s seemingly easy transition quickly dissipated. She began to discover clues that revealed what his years at Carlton Palms had been like.

He still needed constant supervision, and when he took off his clothes, she saw round circular spots where the hair was missing on his upper body and arms, and a white scar across his upper chest, below the shoulder. “What’s going on here?” she wondered, grabbing a camera to photograph them. She was shocked, too, at his protruding rib cage and hollow cheek bones. He was down to 153 pounds on his 6-foot, 5-inch frame.

She soon found he had acquired strange new habits, too. He’d grab food as soon as it was put in front of him and stuff it in his cheeks, like a chipmunk. “He’d say, ‘Go to your room, no Pizza Hut,’” Kennedy-Shields recalls. Her family never ordered from Pizza Hut, and she had certainly never punished Adam by withholding food. Besides, he had a milk allergy and was not supposed to eat dairy. He also said things like, “you motherfucking little bitch” that he hadn’t heard at home. Sometimes, he changed the pitch of his voice—as if mimicking someone who wasn’t there—when doing it.

“Every day it was something else,” Kennedy-Shields says. “I would pick up that something was wrong, something was wrong, something was wrong.”

Then one day, shortly after he came home, he walked out of the bathroom and began screaming and shaking his head back and forth. He started hitting himself with a ferocity Kennedy-Shields had never witnessed. He was slapping his head and trying to bang it into his knee. “He was making himself bleed,” she says. “He was beating himself.” She had no idea what had set him off or how to stop him. She and Noah grabbed Adam’s arms and tried to talk to him, but it was as if he didn’t see them. His hands shook uncontrollably.

“It was very scary,” says Noah. He realized his brother—so long a benign presence—had come home a different person.

Adam grew agitated when someone stood in front of him or moved too quickly toward him. He’d stare blankly and tremble. He seemed to be in a trance when upset—he didn’t even appear to recognize his own mother. He refused to swim in the family pool and frequently grew upset while in the bathroom. He would punch holes in walls, shred clothes. A few times, he woke up at night and smeared feces on himself. Kennedy-Shields was wary of taking him out in public. At home, the family used a helmet, mitts, pillows, and padding to protect Adam from himself. She began to build a list of things that seemed to spark his episodes—triggers she says he developed while at Carlton Palms.

“I started to put everything together,” Kennedy-Shields says. “And that’s when I hired the attorney.”

After two years at home, Adam moved to a group home, then to an apartment, and finally to a rental house to live on his own with the help of round-the-clock aides. He gained 90 pounds in the six months after leaving Carlton Palms and grew more stable—without restraints—though he still had episodes when what seemed like a “fight or flight” instinct kicked into high gear. Kennedy-Shields now had a plan for how to handle Adam’s meltdowns. Still, every time one occurred, she found herself struggling to function.

Her outrage over the dramatic changes in her son continued to simmer. She believed Carlton Palms was responsible. But she still didn’t know exactly how.

The school had maintained detailed records of Adam’s care. But, she says, it had never allowed her to see them. Shortly after Adam left, she received an odd letter from Carlton Palms’s lawyer, saying that portions of Adam’s file had been stolen out of an employee’s car.

Kennedy-Shields’ lawyer put in requests—in 2008, 2009, and 2010—for records on the use of restraints on Adam and about other incidents involving him, to no avail.

She wanted to send a message and hold the program accountable. In late 2011, she filed a lawsuit in federal court, alleging Adam had suffered permanent injuries and seeking unspecified damages. A judge kicked the suit to state court.

As the case dragged on, Kennedy-Shields watched closely for news about Carlton Palms. The media carried accounts of complaints filed by the state against the facility. The accusations were staggering: When a boy at Carlton Palms refused to lie face down for a restraint, a staffer had kicked him in the head and choked him. Residents had been beaten, dragged across the floor, and struck with a plastic container that caused an open head wound, the state alleged. In 2013, a 14-year-old girl with autism died there after a night in which she projectile-vomited while being tied to a bed and a chair.

Then one day in the summer of 2014, an envelope from Kennedy-Shields’s Tampa personal injury attorney arrived in her mailbox. It contained a flash drive holding documents that Carlton Palms had finally released about Adam’s time there.

Hunched over her son Noah’s laptop computer, Kennedy-Shields clicked on files containing the narrative of her son’s days that she’d both yearned for and feared. She learned that staffers had given Adam meals like macaroni and cheese, despite his dairy allergy. He’d once climbed over a fence and splashed in a lagoon where she remembered seeing alligators sunning themselves during her visits. He had hurt himself falling off a swing. A staff member was fired after hitting him.

But it was the restraints that took her breath away.

She had steeled herself before she looked at the files, expecting to read that in his final months at Carlton Palms, Adam had been shackled in restraints, as the wound she had spotted suggested. Then she saw the date.

Carlton Palms reported that a restraint had occurred at 10:20 a.m. on June 17, 2001—roughly seven months after Adam arrived at the school, when Kennedy-Shields had thought everything was fine. She felt her heart quicken as she realized that Adam had been tied up and pinned down for years without her knowledge.

After a few minutes, she shut the files and called her attorney, furious. She couldn’t bear to see more.

Weeks passed. Depositions were scheduled for her and Tom Shea. Bracing herself, she knew she had to read on.

There were more than 750 pages of records. In dispassionate terms, the records revealed repeated incidents of Adam refusing to follow directions, escalating his behavior as workers intervened, and ending up forced into a wrap mat, or with his ankles shackled or with his wrists cuffed against a waist belt. Shea was notified directly of some incidents, records said. Interspersed were reports of injuries Adam suffered in and out of restraints.

Some restraints occurred in response to what sounded like dangerous behavior, such as his hitting himself or banging his head. But others hardly screamed emergency at all. One time, Adam refused to clean up Legos and ended up in mechanical restraints. He was put in them, too, for an incident that began with his smiling and throwing a toy across the room. His ankles were bound after he tossed a dinner bowl and broke it, and after he launched couch cushions across the room.

Some episodes seemed more punitive than safety-related—he was placed in a wrap mat “because he hit Matt in the head,” a staffer wrote, for instance—or even for convenience: “It was in the best interest of the great room to put mechanical restraints and use the protective wrap mat.”

Kennedy-Shields stopped reading so she could run and vomit, then she sat down on her kitchen floor and sobbed, knowing she finally had the answer to the question she had asked Shea nearly seven years earlier. Noah came over and kept reading, stopping at one point to throw something across the living room in anger. They pressed on through the night. Together, they finally learned the secrets Adam had never been able to tell.

In the spring of 2015, more documents arrived from Carlton Palms. Adam’s “behavior plans” laid out the habits that were causing him problems and described what the facility was doing to address them. Parents were supposed to consent to treatment options and sign forms when new plans were written. But despite yearly updates that showed Adam’s behavior getting worse—not better—as Carlton Palms used progressively more forceful means to control him, Kennedy-Shields only recognized the first plans as ones she had seen and approved.

The plans told a heartbreaking tale. A “handsome young man” who enjoyed music and being outdoors arrived at Carlton Palms in November 2000, seeking help with his speech and a decrease in socially disruptive, but typically not life-threatening, behaviors like hand-biting and slapping. His aggression, an admissions document said, was “not very frequent” and “not very sophisticated.” He slept well and had a good appetite. He was not on any medication.

The years ticked by, and his behavior worsened. He started hitting himself and scratching until he bled. His behavior got more intense when he was ill—and he was often ill—as he endured chronic sinus congestion, headaches, and ear infections. The plans recognized that medical problems triggered his outbursts, but also attributed them to his desire to “escape from demands”—or, essentially, to ignore instructions.

Clinicians responded by upping the ante: At first, he was given a sort of “time out” away from others. By 2003, the plan called for the use of the wrap mat for five minutes plus one minute of calm—though records show Adam had been subjected to it before. Later, a “range of motion” device was added to the plan—a waist belt with wrist cuffs that can be clipped to it to force users’ hands to their sides.

By 2005, the description of Adam had changed dramatically from the original admissions forms Carlton Palms staffers had filled out. The new plan said he was admitted to the program because he had “attacked his younger siblings and has eloped from the house into dangerous situations” and that “within the home they could not offer the kind of 24-hour supervision that he required ensuring safety.” It said that, “While living at home his family would have to take turns staying up at night to ensure that Adam did not run away or self-injure.” None of that was mentioned in the intake forms. And it hadn’t happened while Adam was with Kennedy-Shields, who says she took care of Adam for all but a few hours a month.

The 2005 plan raised the possibility of finding a placement closer to Tampa for Adam. But Carlton Palms behavioral specialists asserted that any place would need the same strong measures—mechanical restraints like a wrap mat, 24-hour supervision, locked premises, and a well-staffed facility—to control him. Those parameters suggested few, if any, other homes would work.

By 2008, Adam’s plan said that if he wouldn’t stop his aggression or self-injury, workers should bind him in the wrap mat until he was quiet for one minute, then secure him in the “range-of-motion” device until he was calm for an hour.

The last year Kennedy-Shields’s signature appeared on a plan was 2002, documents from Carlton Palms showed. Forms attached to a few other plans were signed by Fields, Adam’s now-estranged adoptive father, who did not have custody but visited him a few times. Kennedy-Shields, in contrast, says she talked with Carlton Palms staff several times a week, visited regularly, and had a fax machine at home. She was Adam’s legal guardian. Neither Adam’s father, nor the facility, told her what was in those plans, she says.

In 2004, clinicians had Adam sign the parent consent line himself, though he can’t write. In 2006, the signature—presumably his—is wavy scribbles that don’t resemble letters. On another plan, a clinician who drew up the plan signed her own name on the parent consent line, adding, “conv. with mom.” (Kennedy-Shields says no such conversation took place.)

The plans aimed to justify Carlton Palms’s hands-on approach with Adam. Top administrators at the center—including Shea signed off on them. A peer review committee that considered them sometimes included state officials alongside Carlton Palms representatives.

There were other revelations in the records Kennedy-Shields received. At one point in 2007, a physician authorized workers to pin down Adam with a bed net a blanket of woven mesh that is fastened to the bed frame and stretched across patients so they can’t sit up or fully move their arms or legs. The records don’t say how often it was used, if ever. Another document revealed that Adam wasn’t the only resident who was underweight—a 2005 letter from a nurse listed a dozen residents whose weight was dwindling to the point of concern.

It turned out the support coordinator was wrong when he insisted Adam would not be touched at Carlton Palms after Kennedy-Shields’s confrontation with Shea. Workers tied Adam down at least 44 times in the roughly two months before he arrived home. Some occurred in the middle of the night.

It is hard to visualize what happened in some of the incidents, or to know why staff felt the danger was significant enough to warrant restraints. In one instance, a staffer wrote, “Begin scratching his legs and back, while sitting in a Fetal position.” There was no mention of why he might be itching, or whether something less drastic—treating dry skin or allergies, clipping his nails or putting mitts on him—would have quelled his urge to scratch.

Adam was also getting hurt a lot. Roughly six weeks before leaving Carlton Palms, he was sitting listening to headphones, then took them off and began scratching and slapping himself. He was put in a wrap mat. While he was in it, another resident walked over and kicked him in the face. Then, barely two weeks later, workers noted that he had a black eye—offering no explanation in the documents for the swollen and discolored eyelid. A day after that, “staff found client Adam bleeding from the head” because of an unexplained half-inch cut.

The plans and restraint forms revealed that Adam was getting unmistakably worse during his time at Carlton Palms. By his final year there, he no longer slept through the night, had been on and off antipsychotic medication, and sometimes tried to seriously hurt himself.

After spending hours poring through the paper trail on her son’s care, Kennedy-Shields reached her own conclusion about what Carlton Palms had done to Adam: “They,” she says, pausing, “tortured him.”

One bright, cool morning this spring, I visited Adam. Six months earlier, Kennedy-Shields had moved him into his own small rental house, with a brick front walkway and a screened-in back porch. It is utilitarian, not fancy, with a huge flat-screen television that is turned up too loud. Warm sunlight streams through ceiling-level windows, and Adam is snuggled under a blanket on a soft leather couch.

He says good morning in muffled tones, his gaze shifting around the room. He is excited to go to lunch with his mom. “Van ride!” he says, working on sewing shoe laces through holes in a bunny-shaped card.

Adam, now 31, spends his day playing with toys, such as Mega Bloks, and doing simple chores, guided by round-the-clock aides who are paid for by Medicaid. His brother Noah, who is studying to become a behavior analyst, works with him daily. Adam can easily visit his family’s house a quarter-mile away, but if he gets overwhelmed, he has his own space to return to.

Kennedy-Shields gives Adam a candy cane for doing something she asked. He crunches through it, holding it in his enormous hands and taking giant bites as if it’s a carrot stick. He moves on to a turtle lacing card.

He starts to whine and squeal, which can be a precursor to agitation. “Hey, excuse me,” Kennedy-Shields says, trying to quiet him. “Who loves you, baby?”

Adam settles down to play again. “This is my kid,” she says, “He should have stayed this way.”

He can fold laundry and do easy tasks like shredding paper. “He could have had supported employment,” she says. “What they did is they ruined his life. In every way, every way. They ruined mine,” she says, tears collecting in her eyes. “Because he should be like this all the time. This is what he’s like.”

Kennedy-Shields is girding herself for a trial in her case against Carlton Palms, which she expects will take place in 2016. She still doesn’t think she has seen all of Adam’s records, and her lawyers are trying to get Carlton Palms to turn over the rest.

She monitors Adam’s care closely now. Video cameras are mounted in full sight throughout his house. Rigged to her cellphone, she checks the feed several times an hour. “Any time, any day. In the middle of the night, I’ll just get up and look,” she says.

I ask Kennedy-Shields if Adam has ever hurt her.

When he first came back and went wild, she tried to hold his hands like she used to, to calm him. “His hands are so much bigger,” she says, remembering. He squeezed her finger too tightly, digging his nails in until it stung. He has hit her, too, while flailing his arms. But at those times he had that vacant stare, like the one she first saw at Carlton Palms. “When he hits me,” she says, “he has no idea who I am.”

He is not on antipsychotics. When he gets upset, his caregivers put a pillow in his lap—to keep him from banging his head on his knee—and back off.

He is not restrained, with one exception: His brother Noah sometimes grabs hold of Adam’s hands to stop him from harming himself. Noah is the only one who’s allowed to do that. Scars on Noah’s forearms serve as reminders of the desperate place where his older brother’s mind still goes.

“No one’s hurting him again,” Kennedy-Shields says. “Ever.”

Annie Waldman provided data analysis for this story