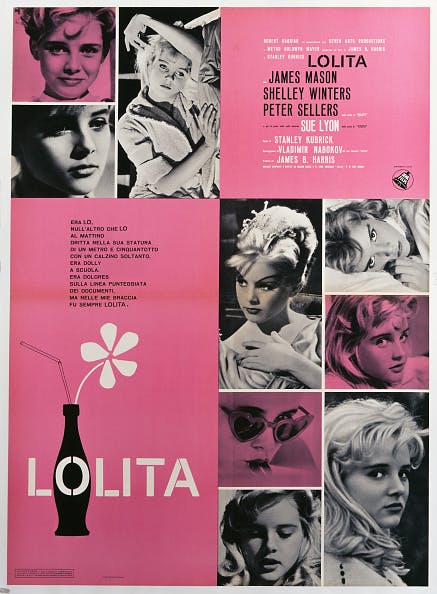

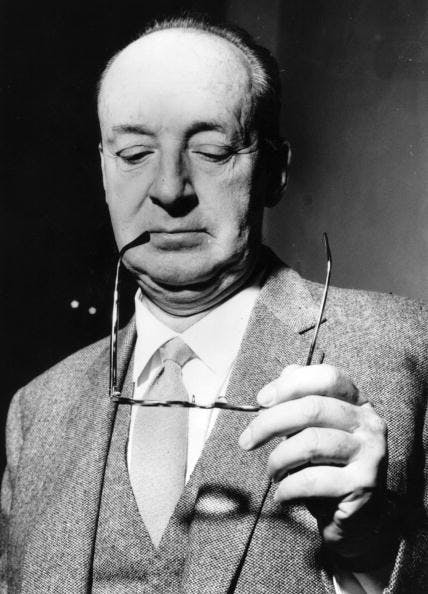

Though Vladimir Nabokov was living in America when he wrote Lolita, the novel was first published in Paris in 1955—by Olympia Press, whose list included many pornographic titles. On the sixtieth anniversary of Lolita’s first publication, we asked ten writers to reflect on their changing experiences with the novel in the course of their reading lives. Each day for five days, we are posting two reflections, each revisiting a section of pages from the book—we are using Vintage’s 2005 edition, a complete, unexpurgated text.

1. Alexandra Kleeman

2. Josephine Livingstone

3. Doreen St. Felix

4. Anna Wiener

5. Moira Weigel

6. Hannah Gold

7. Hannah Rosefield

8. Gemma Sieff

9. Moira Donegan

10. Lidija Haas

1.

By Alexandra

Kleeman, pp. 3-32

At first glance,

Humbert Humbert’s narrative appears to begin in direct address: Lolita, light

of my life, fire of my loins, which is a fitting start for one of the most

notorious love stories in literature. (What, after all, is more romance-like

than calling out for the absent beloved?) But Humbert’s address leads nowhere.

My sin, my soul, he continues, leaving the reader uncertain whether he refers

to the girl or to himself, or to the latter in the guise of the former. Humbert

isn’t speaking to Lolita at all: he uses her instead as material for thought,

something to give shape to his speech. Lolita’s allure has more to do

with Humbert’s backstory than with any nymph-like nature of her own.

That the eponymous girl makes only a fleeting appearance within the first thirty pages of Lolita offers a perplexing answer to the question of whether any male author—even an exceptionally skilled one—can craft an authentic female character. On NPR’s list of the “100 Best Fictional Characters since 1900”, Humbert Humbert is ranked third, Lolita fourteenth. Fourteenth seems generous, given that it is so difficult to perceive Lolita through the haze of Humbert’s elocution (or is it invention?).

Once when I was twenty-four, I went on a date with a man a year older who had never kissed anyone before. When I showed up at his apartment for dinner— a sweet Riesling, green salad with no dressing, roasted chicken with no skin because he disliked the alternating crispiness and flabbiness of it, the goosebumps on its surface—it was obvious that he intended to change that, via me. After we ate he let me choose from a small stack of sci-fi DVDs that he owned. When, ineluctably, he kissed me, his grip was too tight on my body, as though he had expected someone smaller. It was like being marched through someone’s private idea of a perfect night, a night where I was the center but one that had curiously little to do with me at all—all of which is to say that in an equation of desire, the object of desire can be integral and incidental at the same time.

It could be said that

in these early pages Nabokov signals his intent to craft a more honest portrayal

of a female character than any before: A portrayal in absentia, one which has

the reader peering anxiously through the gaps in Humbert’s account for glimpses

of the incidental girl, the one who resists appropriation by narrator and

reader alike.

2.

By Josephine

Livingstone, pp. 33-62

Humbert Humbert has

left a polar expedition, briefly become insane, and, finally, arrived to stay

at a Mr. McCoo’s American house only to find that it has burned down. Instead,

he must lodge with local Mrs. Haze. “What could I do?” Humbert says. “I pushed

the bell button.”

The first perfect

sentence in the book happens on page 57 of Vintage’s

anniversary edition, when our narrator is renting a room in the Haze household

for an “ominously” low price:

I want my learned readers to participate in the scene I am about to replay; I want them to examine its every detail and see for themselves how careful, how chaste, the whole wine-sweet event is if viewed with what my lawyer has called, in a private talk we have had, “impartial sympathy.”

What are we to observe? That the man who we have already heard to possess “a cesspoolful of rotting monsters behind his slow boyish smile” is in fact “careful, chaste.” Ah, but! With the mention of lawyer and impartial sympathy we are recast as juror, and so reminded that the relationship between narrator and reader is no innocent one. Remember the page before, this sentence says, while it pretends to ask for forgiveness. We are not reading about events, but events “if viewed” from the jail cell, looking back.

The scene he has warned us about is simple and grotesque. Humbert Humbert sits in “white pajamas” with “a lilac design on the back.” He is “like one of those inflated pale spiders you see in old gardens.” A predator in floral sleepwear, he waits for his opportunity to snag Lolita for the first time. “The implied sun pulsated in the supplied poplars.” More perfect sentences. More reminders that we are being forced to consume the sublime as a kind of salad dressing soaking a horrible banal middle-aged man in pajamas. A little while later, he has “crushed out against [Dolores Hazes’] left buttock the last throb of the longest ecstasy man or monster had ever known.” Later on that same page: “I felt proud of myself. I had stolen the honey of a spasm without impairing the morals of a minor. Absolutely no harm done.” And you, learned reader—you have participated in the scene! With impartial sympathy, I hope.

3.

By Doreen

St. Felix, pp. 62-93

Charlotte Haze knows. I am on my tenth or so read of Lolita, across as many years and stages of womanhood, and I am beginning to see her agenda. Perhaps not at the moment Humbert cast his gloriously vile gaze on her daughter Dolores—so obsessed she was with his swarthy European look—but she knows what he’s after well before she finds the scholar’s diary. The most pathetic mother character in fiction, then, might have at least been evil. Consider the Humberts’ summer without Dolores.

Charlotte sends

Dolores to summer camp, leaving Humbert writhing in the child’s bedroom. She

sends him a letter by way of the maid, where she declares a succession of funny

things: “If you decided to stay, if I found you at home...the fact of your

remaining would only mean one thing; that you want me as much as I do you: as a

lifelong mate; and that you are ready to link up your life with mine forever

and ever and be a father to my little girl.” Charlotte’s disdain for her child

runs deeper than useless jealousy; for Dolores, both her mother and soon-to-be

stepfather have uses. Charlotte baits Humbert with Dolores; he says yes; she

joins him as a Humbert. Dolores feigns unconcern.

A summer of laughable seduction ensues. The new wife spends the hot months awkwardly affecting girlish coquetterie to summon her husband’s interest. Charlotte looses her breasts on the beach to ply Humbert, while he dreams about Dolores’ blond legs turning brown. Charlotte suggests they take a lover’s trip to England, away from that which he cannot be away from; he fantasizes about drugging both mother and nymphet for two different, related reasons. If Charlotte is evil, what’s worse is she is a poor tactician. “Little Lo, I’m afraid, does not enter the picture at all, at all,” Mrs. Humbert explains. She will send their daughter off to boarding school to receive “some sound religious training” and then “Beardsley College.” Reeling, Mr. Humbert plans impotently to drown her.

She’ll die—his wives always die—but not that way. Charlotte’s knowledge of Humbert’s predilection was perhaps incomplete. But I submit Charlotte understands that making him love her must involve dangling her child in front of him and then snatching her away. To disappear Dolores, Charlotte says her name less. In turn, her husband thinks her nickname and all its diminutives, Lolita, incessantly. That was Lolita’s predictable influence on language, too: Lolita came to be a name for what are called sexually precocious girls but doting, pedophillic men did not come to be called Humberts.

4.

By Anna Wiener, pp. 93-123

“There is a hotel I remember, Enchanted Hunters, quaint, isn’t it?” Charlotte Haze says with ardor at the close of Chapter 21. “And the food is a dream.”

Charlotte and Humbert

Humbert’s romantic getaway never comes to pass. The closest approximation to

actualizing a fantasy is its documentation; Humbert is a diligent scribe, and

Charlotte, an industrious snoop. Despite the deployment of every diarist’s most

unoriginal cover story—“The notes you found were fragments of a novel”—

Charlotte is horrified by Humbert’s betrayal and his salacious intentions for

her daughter, Dolores/Lolita. She races from the house and into the path of an

oncoming car. Exit Charlotte; enter Papa Humbert, consummate caretaker. Master

of the long con, he weaves a fictitious alibi for Charlotte (emergency surgery;

imaginary hospital; eventual death), and travels to collect Lolita from camp,

bearing lurid gifts and lewder fantasies.

Humbert and Lolita

embark on a uniquely American adventure: a road trip. They bounce along the

highway, pulling onto the shoulder to kiss. Navigating the car through

small-town darkness, Humbert’s narration grows increasingly tumescent as The

Enchanted Hunters remains out of reach. The Enchanted Hunters has a quintessential

sad-motel aesthetic, its gestural romance and girlish decor the antithesis of

sex: floral carpets, chenille bedspread, ruffled lampshades. The dining room is

“spacious and pretentious,” with “maudlin murals depicting enchanted hunters in

various postures and states of enchantment amid a medley of pallid animals,

dryads and trees.” Over dinner, Humbert enchants Lolita via purple sleeping

pill (“Oh, how fast the magic potion worked!”) and they return to their room,

with its omnipresent mirrors. “There was a double bed, a mirror, a double bed

in the mirror, a closet door with mirror, a bathroom door ditto, a blue-dark

window, a reflected bed there,” Humbert writes.

“I’ve been such a disgusting girl,” Lolita says, passing out on the bed; you can picture the child bewitched in slumber, her wilted body repeated across each silvered surface. This panopticon is designed for the predator: his prey has nowhere to hide. The food, as Charlotte promised, is a dream.

5.

By Moira Weigel, pp. 123-154

Lolita is the story of

a doomed chase. More specifically, it is a story about the fate of a European

tradition that understands desire this way. Since the beginning, Humbert has

been setting himself up as an heir to Dante and Petrarch. When this section

begins, Humbert Humbert is killing time downstairs at the Enchanted Hunter; Lo

is locked in room 342, lightly drugged by a sleeping pill. Humbert is giving it

half an hour to do its work. Yet, he remains nervous. As he tells us, “lust is

always unsure.”

In Chapter 30, instead

of simply describing their days at the Enchanted Hunter, Humbert sketches an

elaborate emblem in the subjunctive. “Had I been a painter… this is what I

might have thought up… There would have been a lake. There would have been an

arbor in flame-flower...” Counterfactual on counterfactual. We know from the

beginning that this fantasy, like the transient beauty Dante and Petrarch

celebrate, is living on borrowed time.

In this section, the old, and often irritatingly erudite voice of the Euro-cosmopolite who in so many ways resembles Nabokov collides with the vastness of a new and expanding America. For all the literary allusions that Humbert heaps on her, Nabokov presents Lo herself as an utterly average “teen.” She has conventional crushes; her lips are red, “like licked candy”; she is constantly reading movie magazines. Lolita, the book, is not immune. The plot relies on a machinery of improbable coincidences and violent actions that would fit perfectly in a Hollywood melodrama.

When I was a few years older than Lo is supposed to be, I adored Lolita for its word games. I longed to be as sophisticated as its narrator, smart enough to get his private jokes. Twice the age now, I am struck rereading it how many fancy words I must have learned here first. Limpid! Alembic! Concupiscence!

Today, my feelings about Lolita are more ambivalent. Not because it celebrates sex abuse but because it fervently believes in the autonomy of art from life. Nabokov insists that a private, even hermetic experience of literature is enough to redeem the horrors of real history—the fallen continent Humbert fled. I disagree. Yet the skill with which Lolita creates and sustains its double vision, still impresses and affects me deeply, even as the Old World that produced Humbert shrinks ever smaller in the rearview mirror.

6.

By Hannah Gold, pp. 154-183

When I first read Lolita I was in high school and thought that what made it “great literature” is that it forces the reader to identify with such a low and frightening character as its narrator Humbert Humbert. Not fully understanding why, I quickly became obsessed with the book—making lists of every word I didn’t know, writing a short story about a man who’s sexually attracted to his pet rabbit. Soon “lepidoptery” called to mind liver-spotted men and lechery, especially since I never used the word.

Now it seems to me a

book in which every sense except sympathy is aroused. Nabokov’s frantic,

flourishing imagery is the flattened gas pedal of style. Read the words out

loud and you’ll start stumbling over them, or into them—anyway, making roadkill

out of them. Nowhere is this need for speed better realized than in these pages

of the book that recount the year that Hum and Lo spend tripping across America.

Humbert has just finished explaining to Lolita, with surgical cruelty, that she can either get in his car or become a ward of the state. From there, during “150 days of actual motion” and “200 days of interpolated standstills,” the two travel around the entire country, from Texas to California to Kansas, in no particular order. Along the way Humbert examines his legal status, which changes by the state and therefore by the day; in Alabama he’s a kidnapper, in Missouri he’s a legal guardian (he’s a sex offender everywhere).

There are pit stops at inns, with soda fountains and swimming pools. In California, Humbert gives Lolita tennis lessons. They go to the movies some two hundred times, where they watch news reels, Westerns, musicals. In the summer Humbert comes close to getting caught after forcing himself on Lolita outdoors, along a mountain pass. He suffers and grumbles that he will never be able to peer into Lolita’s innards, “her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys.” Apart from this Humbert sees everything America has to offer, or at least catalogues it. His motivation is to escape being seen anywhere for too long.

Above all, these pages are solidly some of the best in the book because they contain Humbert’s reference to himself as a “Humburger.” It’s hilarious, brief, totally unrelatable.

7.

By Hannah Rosefield, pp. 183-215

“I once read a French detective tale where the clues were actually in italics,” says Humbert. Short of putting the relevant sections of Lolita into italics, Nabokov couldn’t do much more to tell us to keep our eyes open as the novel shifts from romance to mystery.

The noirish details

accumulate: hurried telephone calls, ambiguous names, a gun, a raincoat, a

series of coincidences and motels. Yet I always hurry over these details,

ignoring the clues that could help me solve Dolly’s disappearance. Though I

don’t always have the best head for thrillers, I suspect that even the most

promising Philip Marlowe-in-training would find it hard to pay attention to the

coincidence of a long-gone hotel having the same name as a school play, when

there’s the endless distraction of Lolita herself, morphing from child to

stroppy, secretive teen.

Who can think about

the identity of the playwright—“some old woman, Clare Something”—when Dolly

Haze is coming down the street on her bicycle, chaotic, graceful, “one hand

dreaming in her print flowered lap”? When there’s the gabby stupidity of

headmistress Mrs. Pratt, baring her dentures at Humbert, wondering if anyone

has yet taught Dolly about sex? When we see Humbert handing out dollars and

dimes for sexual favors before right away prizing the money from Lolita’s

fingers, believing that keeping her penniless will keep her his prisoner? Reading

Lolita, missing all the signs, I find myself not only as enchanted but as

foolish, as scornful, as oblivious as Humbert himself.

8.

By Gemma Sieff pp. 215-247

Things are ramping up

for Humbert Humbert (or Otto Otto, or Mesmer Mesmer, or Lambert Lambert) and

his spoil-of-war as they wander west. Tailed by a convertible he calls the Red

Yak, HH is losing touch with reality. If he can’t shake the guy or determine

who he is by aggressively interrogating the fickle little traitor in the passenger

seat, he will try looking up his license plate. He copies it out only to find

its digits mangled by “a child’s hand.” They drive on, HH pulls over, “Lo

looked up with a semi-smile of surprise and without a word I delivered a

tremendous backhand cut that caught her smack on her hot hard little

cheekbone.” It’s one of the few moments of non-sexual violence between them:

the kind of blow a brute bestows a woman. Among other details in these chapters

it signals that Lo is no longer a perfect nymphet. At 14 she is approaching the

end of her nymphancy and HH will lose her one way or another.

HH’s mania is making

him see not double but fractal. “Perhaps, I was losing my mind.” Perhaps! He

regrets allowing Lolita to participate in school dramas, realizing that

pretending on the stage may (must) have taught her to pretend with him. The

magic of her tennis game is in its sweetness, the spin-free sincerity of her

lovely strokes, the absence of drive or a desire to win. HH’s own serve can be

tricky, but he keeps it simple so as to prolong the game. “Who would upset such

a lucid dear? Did I ever mention that her bare arm bore the 8 of vaccination?

That I loved her hopelessly? That she was only fourteen?” Those questions ache

with nostalgia. The 8 of vaccination is years old. She is only fourteen and

already fourteen.

Lolita gets sick, and HH has to relinquish her to the hospital and its prying busybodies. He brings her a ridiculous stack of books when what she wants is all of her clothes, so that she can make a run for it, and with the help of impotent “uncle” Gustave, she does. HH foams at the mouth when he finds out, but keeps it together enough to stay out of jail for now.

9.

By Moira Donegan, pp. 247-281

With Lolita gone, Humbert descends into madness. Destroyed by his grief, he declines to describe the years that immediately followed Lolita’s disappearance. “The general impression I desire to convey is of a side door crashing open in life’s full flight,” he says, “and a rush of roaring black time drowning with its whipping wind the cry of lone disaster.”

During this dark

period Humbert meets Rita, an adult woman “twice Lolita’s age and three

quarters of mine,” who he encounters jovially drunk at a roadside bar. They

spend the next two years as an amicable, shoulder-slapping couple, driving from

motel to motel in a happily drunken montage. His account of Rita’s arrests

and infidelities in various highway towns is brief but offers an uncanny

counterweight to Humbert’s relationship with Lolita. Here we see him again

careening about a vice-filled and mournful America, but this time the affair is

only ordinarily sordid, the sort of thing that happens between two consenting

adults who do not try very hard to be kind to one another.

The emotional climax comes later: Humbert receives a letter from Lolita herself. She is married, pregnant, and needs money. He tracks her down to a glamourless rural town, where the 17-year-old Lolita is living with an anodyne young veteran. The reunion is, as such things must be, a disappointment. “Couple of inches taller,” Humbert recounts. “Pink-rimmed glasses. New, heaped-up hairdo, new ears. . . . The moment, the death I had kept conjuring up for three years was as simple as a bit of dry wood.” He’s still in love, though he can’t contain his repulsion at her adult body and drab surroundings. Humbert gives her a check for ten times what she asked for, and, already knowing her answer, asks her to come away with him. It is perhaps Nabokov’s most arresting accomplishment that her reply contains genuine pity, genuine compassion. “‘No,’ she said. ‘No, honey, no,’” Humbert writes: “She had never called me honey before.”

10.

By Lidija Haas, pp. 281-309

Some of Lolita’s most poignant moments are crammed into the last few pages, where its tangle of the moral and the aesthetic, the wrenchingly sad and the gleefully grotesque, reaches a peak. Here Humbert has what some have wanted to see as partial epiphanies: the voices of children playing prompt him to realize the enormity of having stolen Dolly’s childhood; recalling a chance remark of hers, he vaguely senses that she is in fact a real person with a mind—“that quite possibly, behind the awful juvenile clichés, there was in her a garden and a twilight, and a palace gate—dim and adorable regions which happened to be lucidly and absolutely forbidden to me.”

Yet we can’t take any of this seriously as a redemption. It’s only a little less farcical than that other wrestling match he has with himself in this section, the showdown with his double, Quilty. For all his hangdog expressions of regret, Humbert has his claws in the girl and the reader till the last moment, keeping himself and her alive and locked together via “my writing hand.” In the “refuge of art,” she can’t get away from him and neither can we: “this is the only immortality you and I may share, my Lolita.”

Some readers have always worried about how much of HH there was in VN (sure, it’s art, they say, but why so many little girls?). That line of thought doesn’t lead anywhere especially interesting. But you could say that Nabokov does use Humbert to explore himself in one important sense: What does it mean to have, and employ, such powers, to make worlds out of words that can feel so much more vivid than the real one (and make us feel more for imaginary Lolita than for her real-life prototype Sally Horner, confined by Humbert to a parenthetical aside)? Is someone who can conjure such things doing the rest of us an ethical as well as aesthetic service, or is that virtuosity more like a dangerous perversion in itself? Nabokov would always want to have it both ways.