Could the Supreme Court hear the same affirmative action case three times? Quite possibly.

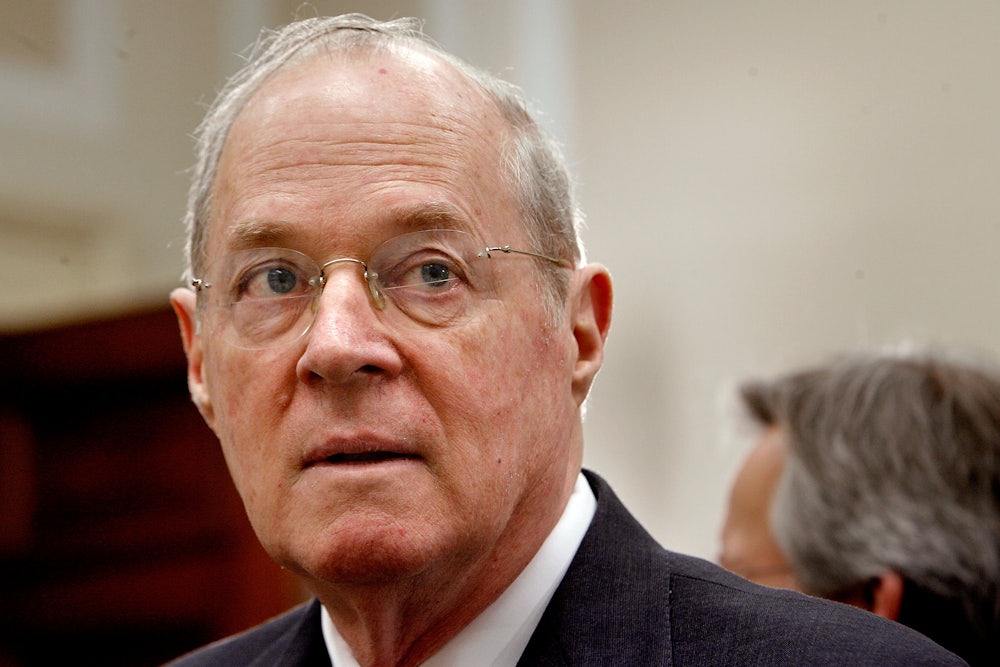

The big news after this morning’s oral argument in Fisher v. University of Texas was that Justice Anthony Kennedy—who is universally regarded as the deciding vote in the case—seemed very interested in remanding the case to the district court for additional fact-finding or a trial on the merits. Early in the oral argument, Justice Kennedy observed that “we’re just arguing the same case,” complaining that “the litigants, and frankly this Court, have been denied the advantage and the perspective that would be gained if there would be additional fact-finding under the instructions that Fisher sought to give.”

Over the course of the morning, Justice Kennedy asked a number of questions of both sides about the possibility of a remand, probing what kind of evidence could be added to the record. By the end of the argument—which was extended by Chief Justice Roberts to give the attorneys extra time to make their case—it seemed clear that Kennedy was searching for a way to avoid having to decide the constitutionality of the University of Texas’s race-conscious admissions program.

Two years ago, Ed Blum brought Fisher to the Court, hoping for a ruling striking down race-conscious admissions programs and eliminating a practice that has helped countless students enjoy the Constitution’s promise of equal opportunity. In a 7-1 opinion written by Justice Kennedy, the Court declined the invitation to gut longstanding precedents approving the sensitive use of race in college admissions.

As Justice Stephen Breyer observed this morning, the ruling in Fisher I—a compromise that “reflected no one’s views perfectly”—affirmed that the sensitive use of race in admissions may satisfy the highest level of scrutiny. It refused, as Breyer put it, “to kill affirmative action through a death by a thousand cuts.” Under that ruling—as Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Breyer suggested today—the university’s plan should be upheld.

But a number of the Court’s conservative justices were looking to reopen the Fisher I compromise, insisting on a form of strict scrutiny so demanding that no race-conscious admissions program could possibly satisfy it. The Court’s past cases have held unconstitutional programs that rely on quotas, insisting, as the Court held in Fisher I, that “admissions processes ‘ensure that each applicant is evaluated as an individual and not in a way that makes an applicant’s race or ethnicity the defining feature of his or her application.” To honor that principle, the University of Texas fashioned a system in which admissions officers do not give specific weight to race, but rather consider all the ways in which a student—whatever his or her race or ethnicity—might add diversity to the academic community.

This morning, in their questioning, Justice Samuel Alito and others suggested the university’s plan was fatally flawed because there was no adequate data on whether the use of race as one factor among many would actually help to increase diversity. That would subject universities to a Catch-22, making it impossible to design a race-conscious admissions program that satisfies scrutiny. That result, of course, is perfectly consistent with Chief Justice John Roberts’s opinion in Parents Involved v. Seattle School Districts—an opinion Alito joined—which insisted that “the way to stop racial discrimination is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

This morning, Chief Justice Roberts called the “power to consider race in making important decisions” an “extraordinary” one that had to be strictly limited. The framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, of course, had a different view. They understood that the government could use race to help foster equality, and enacted contemporaneous with the Fourteenth Amendment race-conscious measures in the field of education to realize the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws.

Of course, the Court’s conservative justices—including the Court’s most fervent originalists—have not given any consideration to the fact that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment originated affirmative action. In the decades-long attack on affirmative action, conservatives have yet to offer any credible response to this critical part of constitutional history.

During this morning’s argument, Chief Justice Roberts also insisted that there had to be a “deadline” on the use of race in admissions, invoking the dicta in former Justice Sandra O’Connor’s majority opinion in the 2003 decision Grutter v. Bollinger, which upheld the sensitive use of race in admissions at the University of Michigan School of Law. In Grutter, Justice O’Connor expected that the use of race would be unnecessary by 2028—a statement she later acknowledged would not actually bind judges hearing future cases—but Chief Justice Roberts seemed ready to think that, 12 years in, we need a definitive ending point.

Roberts’s comments today were similar in tone to his opinion gutting the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder—another case engineered by Ed Blum—in which Roberts pronounced that the Voting Rights Act was no longer needed because “things have changed dramatically” in the South. Despite mounting evidence pouring in from places like Ferguson, Missouri, and Charleston, South Carolina, Roberts seemed ready today to declare that race no longer matters. The truth, sadly, is that it still does.

Justice Antonin Scalia, who was surprisingly silent yesterday when the Court heard Evenwel v. Abbott, inserted himself as well. In one of the most notable moments in the argument, Justice Scalia offered an unfortunate demonstration of the kind of stereotypical thinking that shows why the sensitive use of race in admissions, as Justice Kennedy wrote in Fisher I, aids in “lessening ... racial isolation and stereotypes.” In his questioning of Greg Garre, the university’s lawyer, Justice Scalia asserted that perhaps the University of Texas at Austin “ought to have fewer” African-American students, suggesting that they would be better off at a “slower-track school,” and that the excellent education provided at the university was simply “too fast for them.”

It is comments like these that show why universities need to be able to consider race to assemble a truly diverse student body. This would help break down what Justice Kennedy called—in last term’s landmark fair housing case, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project—the “unconscious prejudices and disguised animus” that, all too often, result from “covert and illicit stereotyping.”

The first Fisher case raised a question of constitutional principle, with Blum’s team seeking to rewrite the Fourteenth Amendment and prior Supreme Court precedent to mandate colorblind admissions procedures. This time around, there is no important question of constitutional law to be decided. As this morning’s argument showed, this case has now become a vehicle for the Court’s conservatives justices to second-guess the university’s well-founded judgment that the sensitive use of race helps to ensure a diverse student body, provide pathways to leadership, and break down stereotypes that stand in the way of equality for all.

The question now, as the justices begin their deliberations, is whether they will conclude this is consistent with the Court’s long-standing precedents, or drag the case out further.