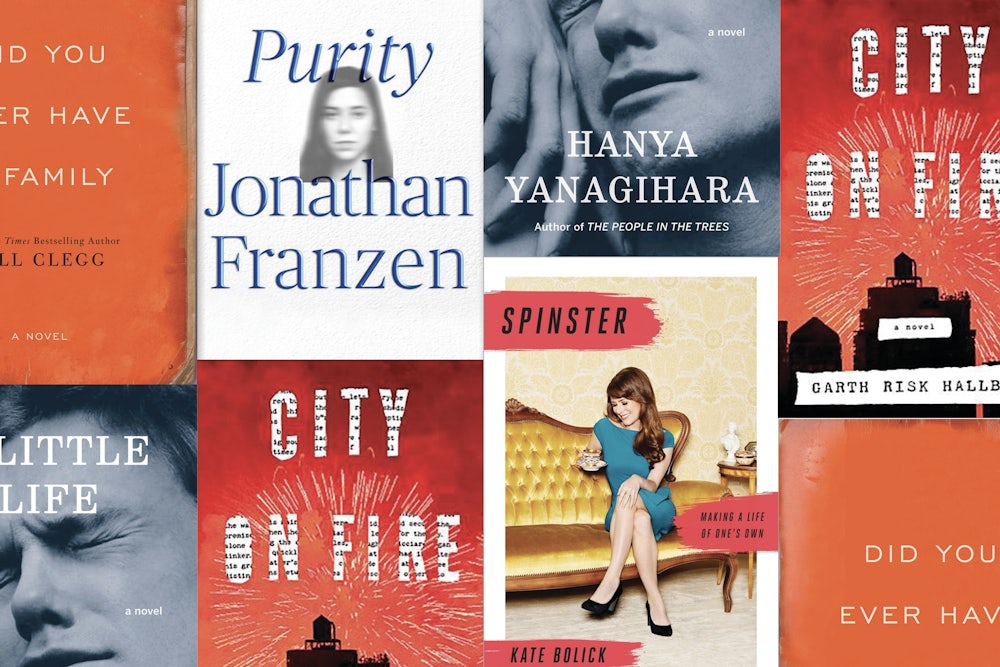

This year wasn’t short on the best kind of book: the type that polarizes opinion. While hype is nice for authors and their publishers, the widely-praised and easily-accepted book is a less enticing prospect for the public than the book critics have disagreed over bitterly. The most important consequence of a wave of adoring reviews, followed by a backlash of negative opinion is that it suddenly matters whether you’re the kind of person who loved A Little Life or just didn’t. It’s one thing to learn, for instance, that this “trauma-packed” novel has become “a runaway hit” with readers. It’s another to have Daniel Mendelsohn declare in the New York Review of Books that the same novel has “duped” its readers into feeling “confusing anguish and ecstasy, pleasure and pain.” If I’m going to read this book, it will be because Mendelsohn disdains it and I need to know why.

Here is your guide to the most hotly-contested, FOMO-inducing books of 2015. Some of these books have been nominated for prestigious prizes while others remain unlaureled, some have sold well and while others have flopped. But they have one thing in common: Negative reviews that have made each of these books far more fun to read.

Did You Ever Have A Family

by Bill Clegg

This unremarkable novel about a family’s disintegration occasioned some pristinely anodyne reviews when it first came out in September. Unlike Clegg’s first book, a memoir of his cocaine addiction while working as a literary agent, his debut novel explores the emotional fallout of a disaster—a house goes up in the flames the morning before a wedding, killing the bride, groom, and several more family members. The story is told from multiple perspectives, all of them heavy with grief and self-importance. The Financial Times called it “heartfelt and convincing;” the Boston Globe called in “absorbing” and “psychologically-astute.” Most puzzling were the reviewers who praised the book by claiming it didn’t have any of the flaws it clearly had. (The Washington Post claimed it “never strains for profundity” and the Los Angeles Times declared it “without… prurience or mawkishness.”)

Then Dwight Garner destroyed it: “We get the author’s point.” He wrote in an intolerant review in the New York Times. “Life is easy for none of us and, as he might put it, funny how time slips away. But these events don’t resonate as they scroll past. It’s like watching someone stir plastic toads in an unlit caldron.” Finding the book undeservingly longlisted for the Man Booker Prize—“a big deal in the book world”—Garner was dismayed that “critics have arranged warm reviews around it like tea candles.” Not this one.

Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own by Kate Bolick

In its April review, The New York Times made some big claims for this “eloquent” and “engrossing” exploration of singledom, which was said to offer “a clear vision not just for single women, but for all women: to disregard the reigning views of how women should live, to know their own hearts and to carve out a little space for their dreams.” In a blurb, the discerning New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm praised the “bracing feminist consciousness” Bolick brought “to bear on the lives of five unconventional women of the past.”

The

chorus of dissent was loud, but also thoughtful. As Laura Kipnis pointed out

in Slate, “the premise Bolick seeks to

overturn—that in this society “you are born, you grow up, you become a

wife”—seems already long overturned to me.” A long essay by Briallen Hopper

in the L.A. Review of Books complained that “the spinster is not typically cool

and stylish”:

You would scarcely guess it from Spinster, but the figure of the never-married woman of a certain age evokes a vast constellation of abrasive, eccentric, no-nonsense, sour, strong-minded, or socially invisible women who were born to inspire drag queens, tomboys, lesbians, late-bloomers, loners, joiners, haters, do-gooders, nuns, divas, misfits, misanthropes, saints, wallflowers, or various combinations of the above.

And in Bookforum the grande dame of empowered spinsterhood, Vivian Gornick, found the book superficial: “Of the joy and terror of actually trying to begin and end with oneself, there is nothing.”

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

I started to hear about A Little Life from friends who had already read it at least twice. Although it came out in March, the novel didn’t start to receive attention from reviewers until reader devotion reached a critical mass. (“Which A Little Life Character Are You?” asked a Buzzfeed quiz.) So closely did readers’ identify with the book’s evocation of unbearable suffering that many posted selfies in which the book cover—a man’s orgasmic, agonized expression—replaced their own faces.

A month after

publication, The Washington Post

called it “extraordinary,” the New

Yorker “elemental and irreducible.” By the time the New York Times published its review in September by staff critic Janet

Maslin, who commented on its “popular success,” Yanagihara had been hired by

the Times style magazine T, meaning reviewer and reviewee were

now colleagues. (Uh oh.) As the Times’s

public editor Margaret Sullivan put it “It’s highly unusual—in fact, almost

unheard-of—for a Times staff writer

to review a book by another Times

journalist.”

But later reviews found the book spectacularly flat. “This is the formula: insert a case of arrested development into a contemporary male version of The Group,” Christian Lorentzen wrote wearily in the London Review of Books in late September. Daniel Mendelsohn in the New York Review of Books found the novel’s scenes of abuse excessive, with Mendelsohn commenting that “you never care enough about [the main character] to get emotionally involved in the first place, let alone affected by his demise.”

Of course, the book’s editor insisted Mendelsohn was wrong, accusing him of making an “invidious distinction unworthy of a critic of his usually fine discernment.” Nope, Mendelsohn responded, “Yanagihara’s slathering-on of trauma is, in the end, a crude and inartistic way of wringing emotion from the reader.” Whichever way the novel affects you, you don’t end up exactly happy.

Purity by Jonathan Franzen

Some reviewers just loved this book! But others spent a lot of time trying to find a solution to the eternal question: Does Jonathan Franzen hate women? In the New Republic’s review, Sam Tanenhaus spoke unapologetically of Franzen’s “otherworldly feel for female characters (if a male reviewer is allowed to say that).”

In Harper’s, Elaine Blair didn’t want to rush to judgment, but after a fair and balanced consideration of his earlier works concluded that “parts of Purity read as though Franzen urgently wanted to telegraph a message to anyone who would defend his fiction from charges of chauvinism: ‘No, you’ve got me wrong. I really am sexist.’” But much funnier is her demolition of the novel’s plot, which revolves around a Julian Assange-like hacker named Andreas, and Purity, a young girl drawn into his circle.

It feels as though Franzen has arrived at the details of Andreas’s biography by working backward through some faulty process of induction. Why would a man want to leak classified documents on the Internet? Because he hates the idea of official secrets. Why? Because he has committed a secret crime of his own. What kind? Murder. Why’d he do it? To help a pretty girl. What? She is being molested by her stepfather, which upsets Andreas because the truth is that he likes sex with teenage girls, too, but he’s not comfortable with that part of himself, and so he feels a homicidal rage toward the stepfather. Still—an actual murder? He’s megalomaniacal with suicidal tendencies! How did he get that way? He had a really bad mom.

Similarly, at NPR Roxane Gay found the novel “so over the top as to feel like farce” and remarked on Franzen’s “passive-aggressive contempt for nearly all his characters.” While the book debuted at number two on the New York Times bestseller list, and currently hovers around 78,000 copies sold, it looks unlikely the September release will hit 100,000 by the end of the year. (Freedom sold 97,000 copies in its first few weeks, even before Oprah chose it for her book club.)

City on Fire by Garth Risk Hallberg

Any book that comes with a $2 million price tag and a lavishly produced trailer is going to raise impossibly high expectations. For some, these expectations were more than met: “Hallberg, with sometimes dazzling finesse, plays with what Mikhail Bakhtin called the “chronotope” of his fictional world—the simulacrum of space/time,” Alex Preston enthused in the Guardian. In the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani liked the book’s “bravura swagger and style and heart.”

But most of us didn’t believe the hype. At New York magazine, Christian Lorentzen (again!) disagreed: “City on Fire is billed as a 1970s punk fantasia, but the vibe of the novel is less punk than emo.” The book is currently ranked number 822 in Amazon’s sales chart, and has garnered a 3 star review from 130 readers on the site. Wading into the debate quite a while after the book came out—ostensibly in honor of the Thanksgiving holiday (slow news week?)—the New York Post called the novel “a steaming pile of literary dung.”