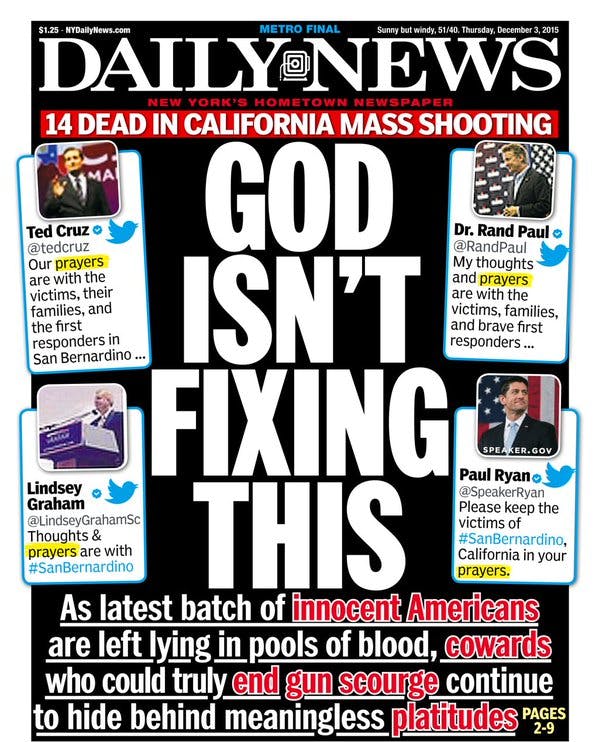

Today’s copy of the New York Daily News reads: “God Isn’t Fixing This: as latest batch of innocent Americans are left lying in pools of blood, cowards who could truly end gun scourge continue to hide behind meaningless platitudes.” This latest “batch” totals fourteen victims from Wednesday’s San Bernardino shooting, an attack allegedly perpetrated by two heavily armed shooters—a married couple—on a facility full of county Department of Health employees having a holiday party. The “cowards” who have the power to address America’s gun scourge are the politicians whose faces and tweets encircle the Daily News’ headline with mentions of prayers for victims and their families, and nothing more.

But prayer itself is not the problem. Rather, prayer is being misused, not only in the public and political sense, but in the religious sense as well. The American public deserves better than dashed-off tweets about prayers in lieu of legislative action—and, crucially, so does prayer itself.

As news broke about San Bernardino, a number of Republican presidential candidates fired off very similar, familiar tweets:

Our prayers are with the victims, their families, and the first responders in San Bernardino who willingly go into harm’s way to save others

— Ted Cruz (@tedcruz) December 2, 2015My thoughts and prayers are with the shooting victims and their families in San Bernardino.

— Dr. Ben Carson (@RealBenCarson) December 2, 2015Many others tweeted their frustration that we’ve all seen these same statements time and time again, yet nothing seems to change. Some employed the mocking hashtag #ThoughtsandPrayers; others were more explicit.

♫♪♫ your thoughts ♫♪♫

♫♪♫ and your prayers ♫♪♫

♫♪♫ can go ♫♪♫

♫♪♫ fuck themselves ♫♪♫

— Jesse Berney (@jesseberney) December 2, 2015Never doubt the influence religion has as training wheels for illogical thinking. https://t.co/pHLtetwd0h

— KStreetHipster (@KStreetHipster) December 2, 2015That these shootings continue to happen in spite of prayer is proof, to some, of the uselessness of praying (and perhaps of all spiritual exercises). For others, the critique of politicians’ prayers in the context of mass shootings is not that praying does nothing, but that that politicians are uniquely equipped to do more than privately pray for victims and their families, and that they are intentionally ignoring those capabilities while scrambling for the moral high ground.

The former criticism—that prayer itself a useless, phatic routine—is likely the more offensive one to well-intentioned religious people. It is also the most likely to produce a rhetorical twilight zone where genuine political complaints are received as personal insults, and the most likely to provide people who would rather argue about Culture War issues than gun policy the perfect opportunity to do so. Suffice to say that several victims and their families specifically requested prayers in the wake of the attack in San Bernardino, and it’s hard to fault others for complying and urging others to join. Yet that always-existing secular frustration with the general worthlessness of prayer is a relatively minor footnote in the broader complaint that has emerged about politicians and their praying.

The greater concern seems to be that prayer on behalf of powerful public figures in the wake of mass shootings functions as a cover for political inaction. ThinkProgress editor Igor Volsky aggregated the “thoughts-and-prayers” tweets and compared them with donations received by said politicians from the National Rifle Association. In his explanation afterward, Volsky thanked followers and retweeters who, along with him, “shamed NRA bought lawmakers for #thoughtsandprayers,” further emphasizing that the problem was not so much with certain legislators’ impulse to pray but with their inaction on the problem of gun control in their capacity as lawmakers. In this sense, the “prayer shaming” wasn’t so much about prayer itself as about empty gestures and the pretense of innocence on behalf of the guilty.

This is a pretty well-established and time-honored complaint. Prayer itself is not the problem; it’s the hollowness of such announcements that seem to strike frustrated onlookers as particularly obnoxious, a reasonable response considering how sincere an act of prayer should theoretically be. (Hollow declarations of prayer should be especially annoying to those who often faithfully pray, following the principle of corruptio optimi pessima: the corruption of the best is worst of all.) After all, there is every reason for people of faith to pray in the wake of mass shootings, especially when staring down the barrel of what promises to be a particularly ugly political battle to reduce access to firearms. And, for believers, prayer should be a constant accompaniment when fighting moral battles, which is likely the reason the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops repeatedly offered its prayers to the families of 2012’s Sandy Hook shooting, while at the same time declaring, quite plainly, that “with regard to the regulation of fire arms ...simply put, guns are too easily accessible.” For the faithful who do wholeheartedly believe that prayer constitutes, among other things, an act of intimate self-disclosure to God, prayer is action, but an action that seeks to shore up strength and wisdom for further action. It is not a white flag.

Which is perhaps why those of us who do pray often and sincerely are so disturbed by many politicians’ empty promises of prayer. Their attenuated political action is one form of underperformance, but then again, so are mere prayers of consolation when it is most necessary to pray for God’s wisdom and guidance in pursuing genuine action on policies that would reduce further carnage. Prayer is not a cosmic Christmas list; it does not, as Kierkegaard once observed, change God; it does have the capacity to change those who pray, including those who publicly announce an intent to pray for others but stop short of seeking the same wisdom and strength for themselves in their capacity as political leaders.

These politicians’ tweets about prayer—contrary to the action of prayer, which both requires and signals hope—seem insincere in light of our pro-gun lawmakers’ repeated belief that mass shootings are inevitable. It’s “the way the world goes”, according to Donald Trump; it’s essentially apolitical, according to Senator Marco Rubio; “stuff happens,” says Jeb Bush. The idea that the United States, through some mixture of bad policy and vice, is destined to suffer daily mass shootings for the remainder of our shared existence arises from a mindset of despair, not hope. It comes from a place of resignation and learned weakness, the sort of failures of virtue prayer is well designed to correct, if those who pray loudly were inclined to pray rightly. It is unfortunate that after the San Bernardino shooting, the frustration of many Americans turned those who desire prayer and political action against those who see so many tweeted prayer intentions as a pardon for inaction, because both sets have honest and compatible complaints. Politicians’ post-massacre prayers shouldn’t conclude their political response to the public health crisis that is American gun violence. It shouldn’t conclude their praying, either.