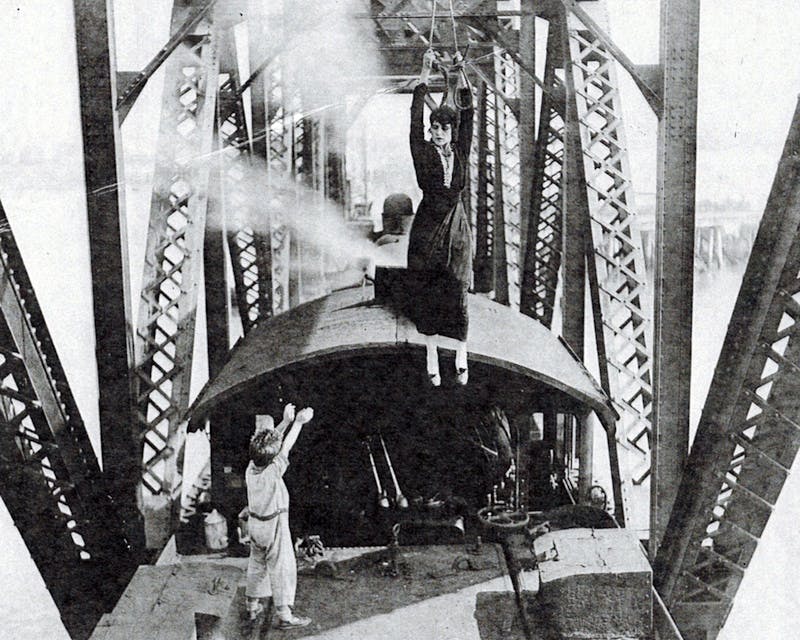

Helen Gibson’s strong, handsome face and dark hair gave her the look of someone who would try anything. In 1915, while in her early twenties, she was doubling for the star of the hit serial The Hazards of Helen. In one stunt she was supposed to leap from the roof of the station to the top of a moving train. Years later, she called it her most dangerous stunt. “The distance between the station and the train was accurately measured,” she said, and she had practiced the jump several times while the train was standing still. But for the shot, the train would be picking up speed for about a quarter of a mile. “I was not nervous as it approached and I leaped without hesitation,” she recalled. She landed safely, but the rocking motion of the train rolled her straight toward the end of the car. Just before being pitched off, “I caught hold of an air vent and hung on.” Then, with a sense of the dramatic, Gibson let her body “dangle over the edge to increase the effect on the screen.” She brought the same strength and flair to scores of other action scenes.

Silent movie actresses like Helen Gibson were the first stuntwomen. They were actresses who could ride horses, drive cars, and do high dives. From about 1910 to the early 1920s, they proved that the “weaker sex” could perform surprising physical feats. During that time, the overlapping advent of movies, automobiles, and airplanes, as well as the possibility of women’s suffrage, set in motion a major cultural transformation in America and around the world. Before they worked in movies, many stuntmen had been boxers, carnival performers, cowboys, or soldiers. Their female counterparts were actresses, dancers, and singers, but most of them had no training or experience in physically demanding performance skills. For women who, up to this time, had been restrained by limited opportunities, these brief, innovative, exuberant years must have felt liberating.

Early on, movies became a force for social change because they reflected the concerns and interests of their largely female audiences. Besides love stories, dramas, and action serials, moviegoers watched films promoting the vote for women, such as the popular What 80 Million Women Want (1913). Since 1848, the movement for women’s suffrage had been found, lost, and found again. As many actresses and future movie stars made their first films in 1910, the state of Washington voted for female suffrage, joining Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho. Clift called it a watershed year, noting that Washington State “paved the way for California in 1911, Oregon, Arizona and Kansas in 1912.” At the same time, America was on the move, and more and more Americans were taking the wheels of new, affordable automobiles—and that meant women, too. Debate raged about women’s “fitness” to drive, with some trying to connect it to their inability to master the technicalities of the ballot. Despite this, cars gave women mobility and independence and opened up the possibility of radically different lives. All this was encouraged by the action captured on movie screens.

Performing in silent films could be as dangerous as it was glamorous. The movies were turned out fast, and there were no safety guidelines. Stunts were experiments in action—someone thought up a car crash and had no idea if it would work until someone else actually tried it. The hazards were real. Film historian Kevin Brownlow described it best: “Stunting in the silent days meant walking on tigers’ tails. It was an occupation with few veterans.” For example, in 1916 actress Mary MacLaren appeared in a film for Universal that required her “to drive an automobile backward down an incline at the rate of twenty-five miles an hour, which she did, losing control and going over an embankment.” MacLaren sued the studio and named her mother as a codefendant, seeking “to break a contract that forced her to undertake dangerous stunts while placing her salary under her mother’s control.”

In What Happened to Mary, serial star Mary Fuller did a scene that was “so absurd . . . nobody should have bothered to chance her life on it.” Mary was playing a mermaid, so her legs were encased in a tail. She was posed on a rock jutting out from shore, thirty feet above the pounding surf, with a bunch of lilies on her chest when she noticed that the tide was coming in fast. “I called out in alarm to my director and cameraman,” she recalled, but they were some distance behind her. “The cameraman was fascinated with the picture and continued to turn the cranks,” Mary said. Her heavy mermaid tail made it impossible for her to get up and run. Spray, then waves, washed over her and swept away the lilies. “I began to move but not towards the shore. My direction was out to sea. I was gasping with fear.” At the last minute, the men looked up from their artistic preoccupations, fished her out, and carried her back to shore. The sea took the camera.

A report on injuries among thirty-seven movie companies from 1918 to 1919 stated, “Temporary injuries amounted to 1,052. Permanent ones totaled eighteen. There were three fatal injuries.” The report called this “a surprisingly low rate of accidents, considering the risk.” But more than a thousand injuries a year does not reflect a safe or trouble-free profession. The industry’s attitude was exemplified by Pathé (dubbed “The House of the Serials”), where Louis Gasnier advised his writers, “Put the girl in danger.” They fulfilled that mission with vigor.

Racing,

crashing, and overturning cars became essential to movie production, and major

stars like petite Mary Pickford set the pace. Who wouldn’t be impressed by

“America’s Sweetheart” leaning into a curve as she hit fifty miles an hour or

Helen Gibson hunched over on her speeding motorcycle? A surprising number of

silent movie actresses were fully engaged in the action. Historian William Drew

described the stars’ close relationship to cars, down to the models they

preferred and how fast they drove. “After all,” he noted, “it was the

actresses, not the actors, who were shattering Victorian ideals of gender roles

through their yen for driving fast cars. Indeed, driving became a virtual

prerequisite for actresses in action-filled films produced when car chases in

those pre–back projection days could not be faked in a studio.”

Actress Helen Holmes wanted to race cars competitively, but that career wasn’t open to women. So she took her motoring skills to movie star Mabel Normand and comedy producer Mack Sennett at their Keystone Company in Edendale, California, near Hollywood. There, she was welcomed with open arms. The filmmaking mayhem at Keystone was good training for Helen’s later stunts, including driving her car at top speed off a dock at San Pedro harbor and making a thirty-foot jump onto a barge for an episode of The Railroad Raiders. Fearless, she succeeded on the fourth try, and the press hailed the stunt as a “hair-raising ride.” Helen’s driving skills would become part of all her serials.

Although Holmes did many of her own stunts, Edward Sutherland or Gene Perkins sometimes doubled her, as did Helen Gibson, one of the first women (if not the first) to double a female action star. Gibson (born Rose Wenger) was one of five daughters, and her father encouraged her to be a tomboy. In 1909 she and a friend went to a Wild West show. “Enraptured,” they asked how they could get jobs on the show, which certainly seemed more appealing than their work in a cigar factory. They were told the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch in Ponca City, Oklahoma, “wanted girls who were willing to learn to ride horses.” Gibson made the cut, and in 1910, at age eighteen, she not only learned to ride a horse but also mastered the trick of “picking up a handkerchief from the ground” at a full gallop. When veteran riders warned her that she might get kicked in the head, she didn’t believe it would happen to her—a confidence stuntwomen have shared for decades.

Rodeos ran from spring to fall, and

the Miller Brothers’ Wild West Show ended its 1911 season in Venice,

California. This allowed its riders to work in the movies during the sunny

Southern California winter. That was how many riders got their start in the

movies, including Tom Mix and Will Rogers. The Kalem Company hired Helen Gibson

in 1912 to appear in one-reelers such as the memorably titled Ranch Girls on the Rampage. She earned

$15 a week—“a big salary for a beginner.” She also rode in the Los Angeles

rodeos, which is where she met future cowboy star Hoot Gibson. They didn’t

consider marriage until they were performing in the Pendleton rodeo and needed

to find overnight accommodations. Married couples were given preference when it

came to hotel rooms, so, Helen recalled, “we decided to get married.”

Today’s stuntwomen are the direct descendants of these silent movie actresses. In the glory years before the 1920s, their action roles in early movies—put in motion by automobiles and powered by demands for suffrage—changed the image and direction of women. Winning the vote in 1920 capped the brief period in which women dominated the film industry. Movies gained more respect in the 1920s as the onscreen stories and the audiences changed. After 1927, talking pictures increased production costs and profits until motion picture production was the fifth largest industry in the United States. The rash, risky exuberance of the silent era had vanished. And in many ways, so did the opportunities for women at all levels of production. For those who survived the 1920s, the 1930s would be even harder. But the story of stuntwomen was just beginning, and like the plot of a great movie, it had everything: humiliation, injustice, injury, death, determination, courage, excitement, and, finally, hard-fought success.

This excerpt has been adapted from Stuntwomen: The Untold Hollywood Story by Mollie Gregory.