Five months is a long time in the life of a revolution. On my return to Cuba for 10 days over New Year’s, I could see that great changes had taken place since last summer. The impressive positive achievements of the Castro regime had been intensified, but so had those aspects of it which must be disquieting to any visiting American. Because my stay was so short, I saw less this time than in July and August. I can, therefore, give only a tentative, personal report; and since our government has now banned further travel to the island, I may not be able to go back for a long time to come.

The most encouraging side of the new Cuba remains out in the countryside, on the cooperatives and the new, heavily-capitalized state farms. Unemployment is down, and agricultural production is up, in some cases spectacularly. It should be borne in mind that Cuba had an enormous amount of unused land and labor available when the revolution came into power, and that the production of such crops as beans and cotton was so low that high percentage increases are misleading. The US Embassy ridicules these claims, but even allowing for a considerable amount of exaggeration it seems clear that production has risen substantially despite all the dislocations attendant upon the agrarian reform program. Having visited the El Modelo state turkey farm in Pinar del Rio Province, and talked with John Michael, the Montana-born manager who runs it, I am convinced that his figures, at least, are correct, and the Embassy’s wrong. Turkeys used to be a luxury in Cuba, with a few hundred frozen birds flown in for expensive Havana groceries; Mr. Michael shipped 42,000 birds out for Christmas, and expects to be producing 50,000 a month at the end of 1961.

Other constructive activities of the regime also continue to be impressive. The housing program, bigger than anything of its kind in Latin America, is going ahead at full steam; the big Havana East Development outside the capital has already admitted its first tenant-owners. Textile workers I talked to in the town of Bauta told me they had been working overtime for more than a year and getting better wages than ever before. Although the amount of money in circulation has doubled over the past two years, rigid price controls have kept inflation in check. Despite the absence of American goods, stores are pretty well stocked with staple items of food and clothing; the economy has survived the shock of the sugar quota cut and the embargo remarkably well. But with dollar reserves nearly exhausted, no American or Cuban businesses left to expropriate, and the Russian and Chinese loans expended on industrial equipment, Che Guevara’s National Bank faces a payments squeeze that even his ingenuity may be unable to overcome. Cuba’s default on her dollar bonds last month, after faithfully meeting interest payments for two years, is probably a sign of an approaching crisis.

Still more troublesome to the regime is the by now massive defection of the middle classes, an element of society much larger in Cuba than in most Latin American countries. Since my last visit, Castro had begun to seize Cuban-owned businesses; in October, with the Urban Reform Law, he wiped out all private investment in urban real estate and began to turn houses and apartments over to the tenants, living in them. These measures alienated well-to-do Cubans who had been pleased to see United Fruit, IT&T, and American and Foreign Power given their walking papers.’ Businessmen, doctors, teachers, engineers and the propertied class in general have turned against Castro, and about 1,000 people a week were leaving the island until the break in relations cut off the possibility of flight. One INRA lawyer, an enthusiastic supporter of the revolution, told me that less than one in three of his professional colleagues was now pro-Castro.

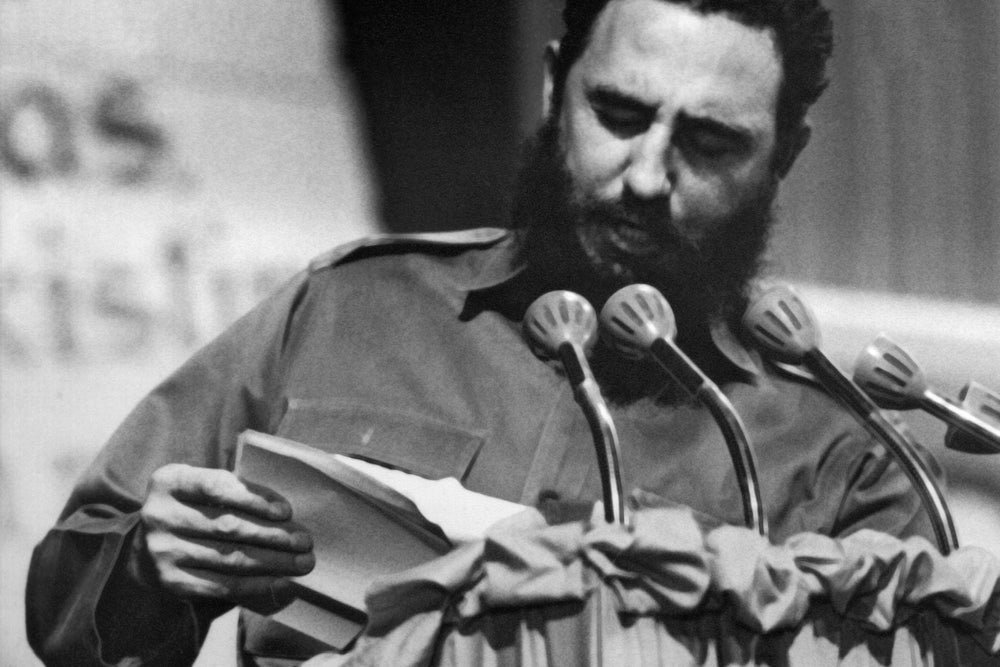

To control internal dissent and to guard against invasion by anti-Castro forces openly training in Florida and Guatemala, the regime has clamped down on the opposition in various ways. Informacion, the last privately-owned paper, and the English-language Havana Times both closed down, for economic reasons, in December; with imports monopolized by the government and most big companies confiscated, advertising revenues will not support an independent press. Radio and television are all government controlled, and Ruby Hart Phillips told me that the New York Times planned to eliminate shipments to Cuba because the National Bank would not release dollars to pay for them. Harassment of foreign newsmen has been stepped up; while I was in Havana, Wilson Hall of NBC was held incommunicado for three days and released without an explanation. I myself was briefly arrested and held for an hour and a half because of an ill-timed attempt at a joke. When a waiter at the airport restaurant told me he was unable to turn down the loudspeakers that were blaring out Fidel’s speech on January 2, I said that I thought a lot of Cubans would be deaf if their ]efe Maximo kept speaking so loud and so often. He hurried off and called the police. I was very politely treated, and released almost at once; some Americans and thousands; of Cubans have not got off so easily.

The Prensa Latina agency that now monopolizes the news in Cuba follows the Soviet line on every question, even such seemingly distant ones as germ warfare in Korea, the Hungarian revolt and the current troubles in Laos and the Congo. When Mikoyan visited Havana a year ago he was visibly embarrassed by anti-Soviet news stories and questions about the satellite nations; nothing like that could happen today. Anti-Communist publications have disappeared from the newsstands, and have been replaced by piles of books and magazines printed in Spanish in Moscow, Peking and the Soviet printing plant in Montevideo. To the dishonesty and distortions of the Cuban press I can give some personal testimony. While I was in Havana I looked up the press attache at the American Embassy, whom I had met last summer. He very courteously offered to arrange a meeting for a group of visiting Americans with Mr. Braddock, the Charge d’Affaires, and we informally stuck a notice up on the bulletin board in the Havana Riviera Hotel. Next day, when the story of “an imminent Yankee invasion” broke, this innocent invitation was cited as “firm proof” that the Marines were about to land; every newspaper printed the completely false statement that the Embassy had called an “urgent” meeting to give “important news” to all American citizens. Mr. Braddock wisely cancelled the meeting, lest it be subject to further misrepresentation. I then called Prensa Latina and gave them the true story; the man at the other end promised to see that a correction was printed, but nothing ever appeared.

Another distressing aspect of the regime, besides its enthusiastic alliance with the Soviet bloc, is the growing influence of PSP (Communist) officials in the government. The head of the National Printing Office is a member of the PSP; to judge from the dozens of Communists from Bolivia, Venezuela, Chile, etc., invited for the New Year celebrations, so are the directors of the newly-formed People’s Friendship Institute. As Ursinio Rojas, a Communist and director of the Havana Branch of the key Sugar Workers’ Union explained it to me, “We have no ideological difference with the Revolution, and we all work together with it. Fidel trusts us because we work hard, and he knows that we aren’t going to run off to Miami some day.” Whenever there are conflicts within the labor movement, Fidel steps in personally and throws his weight behind the PSP element. David Salvador, a former head of the Cuban Labor Confederation, is in jail, after an attempt at surreptitious flight, and the non-Communist officials of the Electrical Workers’ Union were ousted at a meeting packed with fidelistas; their leader, Amaury Fraginals, is in hiding somewhere in Havana.

January 2, the last day I spent in Cuba, was the most disquieting of all. Havana took on the appearance of an armed camp, with field artillery parked along the Malecon Drive, dozens of Russian tanks rumbling through the Plaza Civica, and tens of thousands of marching militia men and women armed with Czechoslovak machine guns. Fidel, obviously disturbed by increasing acts of sabotage and terrorism inside Cuba, and by the barrage of threats and propaganda issuing from Miami and Swan Island, was more violent than ever. He repeatedly warned of an invasion by American forces “before January 20th,” prodded the US into breaking relations by cutting our Embassy staff down to an impossibly small number, and announced that the revolution would search out its enemies in the wealthy neighborhoods, “street by street, and house by house.” Less than 600 people have been executed up to the present time, all of them murderers from the Batista days or rebels captured with arms in their hands. But if the situation gets much worse, a real reign of terror might begin on the island.

What will happen next in Cuba depends to an enormous extent on what President Kennedy and Dean Rusk do in the months to come. The Eisenhower policy of the exchange of insults, economic and diplomatic coercion, and encouragement of anti-Castro military forces, has so far succeeded only in driving Fidel where he was evidently not too reluctant to go, into the arms of Nikita Khrushchev. The new Administration can have no illusions about the possibility of turning the clock back in Cuba or of restoring the island as an economic colony of the United States. Despite the defections pointed out above, I believe that Castro still has the support of a substantial majority of the Cuban people; out in the countryside, I have never met anybody who was not a fidelista. (When I asked the people in Bauta if there were any counter-revolutionaries in the town, they laughed and said, “Yes, there is one. Would you like to meet him?”)

Cuba today has a larger proportion of its people under arms than any other nation on earth; the few abortive uprisings so far have been easily put down by the local militia, led by a few captains from the Rebel Army. Nothing less than a full-scale military operation, with landing craft, air cover, and tens of thousands of troops, could establish a bridgehead on the island; the small Cuban forces training so ostentatiously in the Everglades and at Retalhuleu in Guatemala seem to me to be heading for slaughter, no matter how much help they may get from our Central Intelligence Agency. And a real American invasion of the island, despite Fidel’s fears, is of course out of the question. An official of the Cuban Foreign Office to whom I spoke said that he was dubious about any betterment of relations once Eisenhower was gone, but that with Kennedy in the White House there might be “a little hope.” Despite the giant leftward steps Castro has taken (or has been forced to take) over the past year, it still seems to me that the only sensible course open to us is one of patience, forebearance, and continued attempts to reach some kind of peaceful coexistence with the Soviet bloc’s defiant little ally to the south of us