At some point in the recent past, Black Friday invaded Thanksgiving. While it’s unclear exactly when this trend began, it gained enough momentum by 2007 to warrant a story from The New York Times. “Thanksgiving has long been a day reserved for feasting on turkey and televised football,” the Times noted. But not anymore.

Major chains like Walmart, Target, Best Buy, Kmart, Macy’s, Kohl’s, J.C. Penney, Toys R Us, and Best Buy will all open their doors early on Thursday.

But Black Thursday has also sparked a counter-trend. A Facebook group of consumers pledging not to shop on Thanksgiving Day popped up in 2013. And corporate brands caught on to an opportunity: They would close their doors on Thanksgiving, and even advertise the fact.

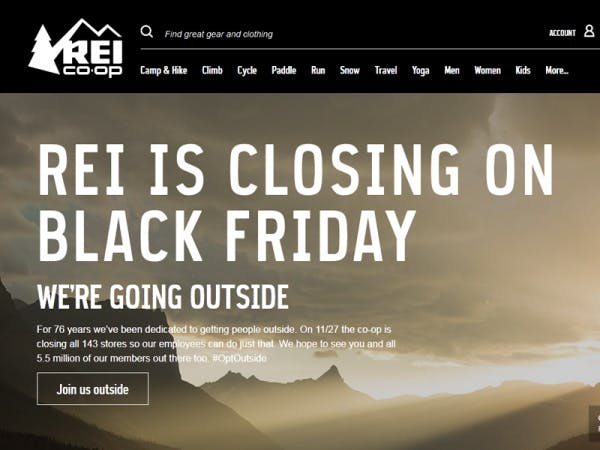

DSW has a banner on its website advertising it will be closed, and released the accompanying statement, “Family time is extremely important to us, and we want our associates to enjoy the holiday with their loved ones.” REI has taken things further, by proclaiming its stores will be closed on Black Friday itself. REI turned the announcement into its own campaign, using the hashtag #optoutside to promote its case against shopping (on Black Friday). Many of the stores’ statements resemble Staples’s reasoning for closing: “We want our customers and associates to enjoy Thanksgiving their own way.” In return, the stores have gotten free press from outlets noting the rarity of a store remaining closed on a national holiday.

Of course, there may be other motivations. Maybe it really is an altruistic move. But it’s more likely chains are hoping to encourage more brand loyalty by ostensibly standing against rampant consumerism. Maybe stores even picked up on news from the National Retail Federation last year that shoppers actually spent less than the year before over the long weekend, a possible sign that they are growing weary of the never-ending promotions.

And while Black Friday creep may seem innocuous enough—perhaps even an appropriately American form of celebration—the burden of opening early is unevenly felt by minimum-wage and part-time workers. As the only developed country that doesn’t mandate any paid time off, the long Thanksgiving weekend has become a luxury, one that’s out-of-reach for many retailer workers.

Furthermore, because the retail sector is already dominated by shift and part-time work, even the workers who “volunteer” for the holidays may not be exercising much of a choice. They may need to work extra hours because the federal minimum wage is so paltry, or may be victim to unpredictable schedules. One practice that’s getting more scrutiny is on-call scheduling, which Mother Jones describes as “requiring employees to be available in case they’re needed for a shift without guaranteeing any actual work or pay.” According to the Economic Policy Institute, 6 percent of hourly workers are tied to on-call schemes, while 45 percent of the full workforce report that employers decide their schedule for them.

This makes it even harder to believe Walmart Chief Marketing Officer Duncan Mac Naughton’s unconvincing claim in 2013 that Walmart workers were “really excited to work that day.”

Thanksgiving shopping isn’t just a nuisance for people who would prefer a more traditional holiday. It’s a reminder of the everyday damage caused by America’s lack of benefits and labor protections.

The initiative to reclaim Thanksgiving certainly doesn’t fix these issues, but it at least puts a spotlight on them. In the meantime, if you really miss shopping for a day, there’s still the internet.