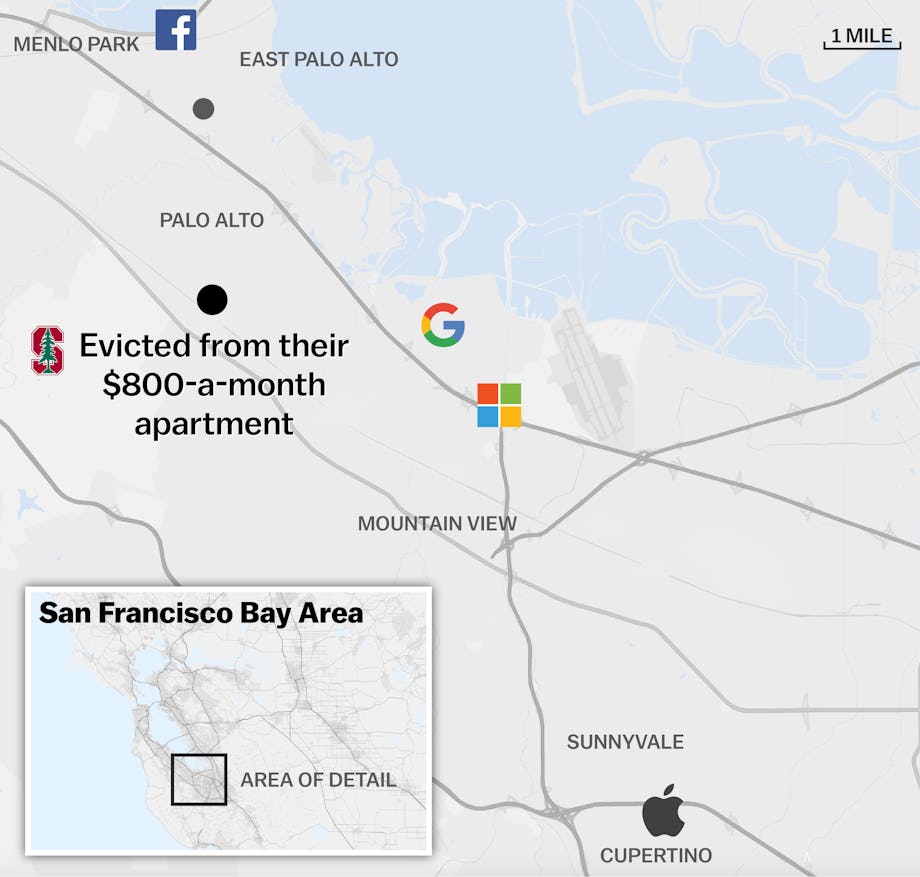

Sometime in July 2012, Suzan Russaw and her husband, James, received a letter from their landlord asking them to vacate their $800-a-month one-bedroom apartment in Palo Alto, California. He gave them 60 days to leave. The “no-fault” eviction is a common way to clear out low-paying tenants without a legal hassle and bring in people willing to pay thousands more in rent. James was 83 at the time and suffering from the constellation of illnesses that affect the old: He had high blood pressure and was undergoing dialysis for kidney failure and experiencing the early stages of dementia.

Their rent was actually a couple of hundred dollars more than James’s monthly Social Security benefits, but he made up the rest by piecing together odd jobs. They looked for a new apartment for two months and didn’t find anything close to their price range. Their landlord gave them a six-week extension, but it yielded nothing. When mid-October came, Suzan and James had no choice but to leave. With hurried help from neighbors, they packed most of their belongings into two storage units and a ramshackle 1994 Ford Explorer which they called “the van.” They didn’t know where they were going.

A majority of the homeless population in Palo Alto—93 percent—ends up sleeping outside or in their cars. In part, that’s because Palo Alto, a technology boomtown that boasts a per capita income well over twice the average for California, has almost no shelter space: For the city’s homeless population, estimated to be at least 157, there are just 15 beds that rotate among city churches through a shelter program called Hotel de Zink; a charity organizes a loose network of 130 spare rooms, regular people motivated to offer up their homes only by neighborly goodwill. The lack of shelter space in Palo Alto—and more broadly in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties, which comprise the peninsula south of San Francisco and around San Jose—is unusual for an area of its size and population. A 2013 census showed Santa Clara County having more than 7,000 homeless people, the fifth-highest homeless population per capita in the country and among the highest populations sleeping outside or in unsuitable shelters like vehicles.

San Francisco and the rest of the Bay Area are gentrifying rapidly—especially with the most recent Silicon Valley surge in social media companies, though the trend stretches back decades—leading to a cascade of displacement of the region’s poor, working class, and ethnic and racial minorities. In San Francisco itself, currently the city with the most expensive housing market in the country, rents increased 13.5 percent in 2014 from the year before, leading more people to the middle-class suburbs. As real estate prices rise in places like Palo Alto, the middle class has begun to buy homes in the exurbs of the Central Valley, displacing farmworkers there.

Suzan, who is 70, is short and slight, with her bobbed hair dyed red. The first time I met her, she wore leggings, a T-shirt, a black cardigan wrapped around her shoulders, and fuzzy black boots I later learned were slippers she’d gotten from Goodwill and sewn up to look like outside shoes. (She wore basically the same outfit, with different T-shirts, nearly every time we met, and I realized she didn’t have many clothes.) Her voice is high and singsongy and she is always polite. You can tell she tries to smooth out tensions rather than confront them. She is a font of forced sunniness and likes to punctuate a sad sentence with phrases like “I’m so blessed!” or “I’m so lucky!” She wore a small necklace and said jewelry was important to her. “I feel, to dispel the image of homelessness, it’s important to have a little bling,” she said.

In the van, Suzan was in charge of taking care of everyone and everything, organizing a life that became filled with a unique brand of busy boredom. She and James spent most of their time figuring out where to go next, how to get there, and whether they could stay once they arrived. They found a short-term unit in a local family shelter in Menlo Park that lasted for five weeks. Afterward, they stayed in a few motels, but even fleabags in the area charge upwards of $100 a night. When they couldn’t afford a room they camped out in the van, reclining the backseats and making a pallet out of blankets piled on top of their clothes and other belongings. Slowly, there were fewer nights in hotels and more in the van, until the van was where they lived.

A life of homelessness is one of logistical challenges and exhaustion. Little things, like planning a wardrobe for the week, involved coordinated trips to storage units and laundromats, and could take hours. The biggest conundrum? Where to pull over and sleep. Suzan and James learned quickly not to pull over on a residential block, because the neighbors would call the police. They tried a church or two, 24-hour businesses where they thought they could hide amidst the other cars, and even an old naval field. The places with public toilets were best because, for reasons no one can quite explain, 3 a.m. is the witching hour for needing to pee. They kept their socks and shoes on, both for staying warm on chilly Bay Area nights and also for moving quickly if someone peered into their windows, or a cop flashed his light inside, ready to rouse. Wherever they were sleeping, they couldn’t sleep there. “Sometimes, I was so tired, I would be stopped at a red light and say, ‘Don’t go to sleep. Don’t go to sleep,’” Suzan said. “And then I would fall asleep.”

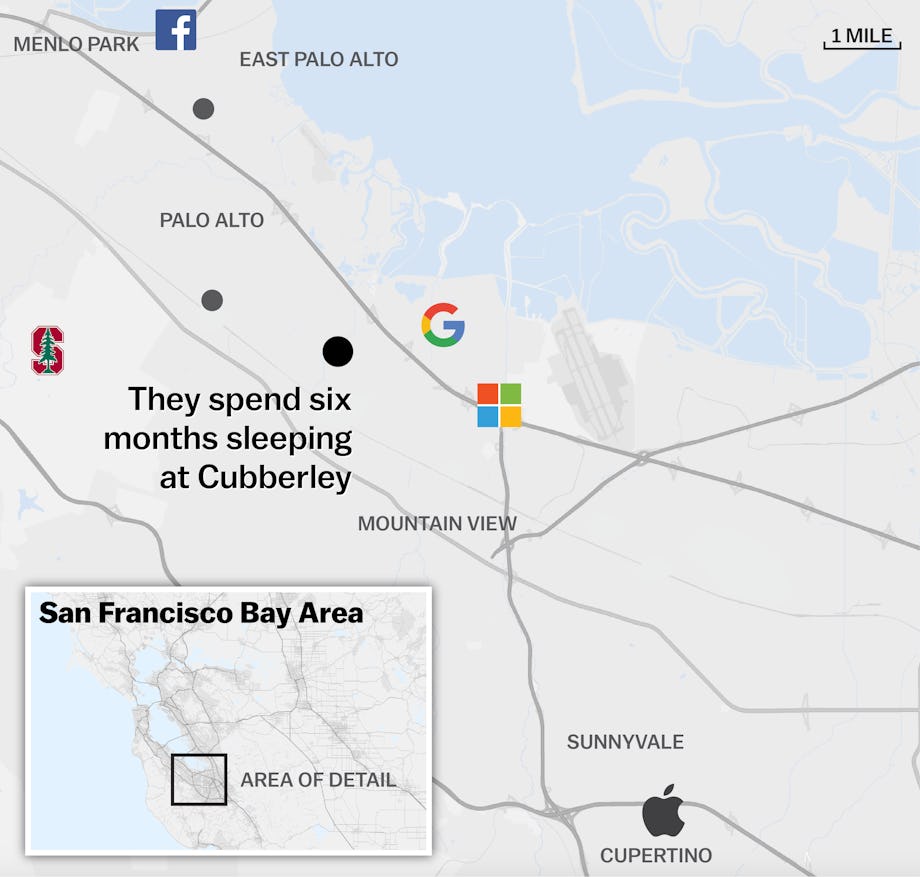

A few months in, a nice man in a 7-Eleven parking lot told them about a former high school turned community center on the eastern side of town called Cubberley. He’d walked up to their van after recognizing signs of life in the car, tired faces among the junk piling up in the back. Suzan and James were familiar with the community center because they’d taken their daughter to preschool there many years before, but they hadn’t thought about sleeping there. Cubberley had a quiet back parking lot, a flat grass amphitheater with a concrete paddock for a stage, and 24-hour public bathrooms with showers in an old gym. Rumor was that the cops wouldn’t bother anyone.

Cubberley was a psychic relief because it solved so many basic needs: It had a place to bathe in the morning, a place to charge your phone. The parking lot had also formed its own etiquette and sense of community. People tended to park in the same places, a spot or two next to their neighbors, and they recognized one another and nodded at night. They weren’t exactly friends, but they were people who trusted each other, an impromptu neighborhood no one wanted to lose after losing so much. It was safe, a good place to spend the night. But it was next door to a segment of homeowners who were fighting hard to move the car dwellers out.

Normally, wealthy people who move into an area don’t see the results of their displacement because the people who lose their homes don’t stick around; they move to cheaper suburbs and work themselves into the fabric elsewhere. But the folks at Cubberley, 30 people on any given night, were the displacement made manifest. Most weren’t plagued with mental health or substance abuse problems; they simply could no longer afford rent and became homeless in the last place they lived. People will put up with a lot to stay in a place they know. “I’ve been analyzing why don’t I just get the heck on. Everybody says that, go to Wyoming, Montana, you can get a mansion,” Suzan said. “Move on, move on, always move on. And I say to myself, ‘Why should I have to move on?’”

It’s a new chapter in an old story. In his seminal 1893 lecture at the Chicago World’s Fair, Frederick Jackson Turner summarized the myth of the American frontier and the waves of settlers who created it as an early form of gentrification: First, farmers looking for land would find a remote spot of wilderness to tame; once they succeeded, more men and women would arrive to turn each new spot into a town; finally, outside investors would swoop in, pushing out the frontiersman and leaving him to pack up and start all over again. It has always been thus in America. Turner quoted from a guide published in 1837 for migrants headed for the Western frontiers of Ohio, Indiana, and Wisconsin: “Another wave rolls on. The men of capital and enterprise come. The ‘settler’ is ready to sell out and take the advantage of the rise of property, push farther into the interior, and become himself a man of capital and enterprise in turn.” This repeating cycle, Turner argued, of movement and resettlement was essential to the American character. But he foresaw a looming crisis. “The American energy will continually demand a wider field for its exercise,” he wrote. “But never again will such gifts of free land offer themselves.” In other words, we would run out of places for the displaced to go.

Suzan was born in 1945. Her father worked at what was then the Lockheed Corporation, and her mother had been raised by a wealthy family in Oak Park, Illinois. Her family called her Suzi. Though she grew up in nearby Saratoga—and spent some time in school in Switzerland—she distinctly remembers coming with her mother to visit Palo Alto, with its downtown theaters and streets named after poets. Palo Alto more than any other place formed the landscape of her childhood. “It was a little artsy-craftsy university town—you find charming towns are university towns.”

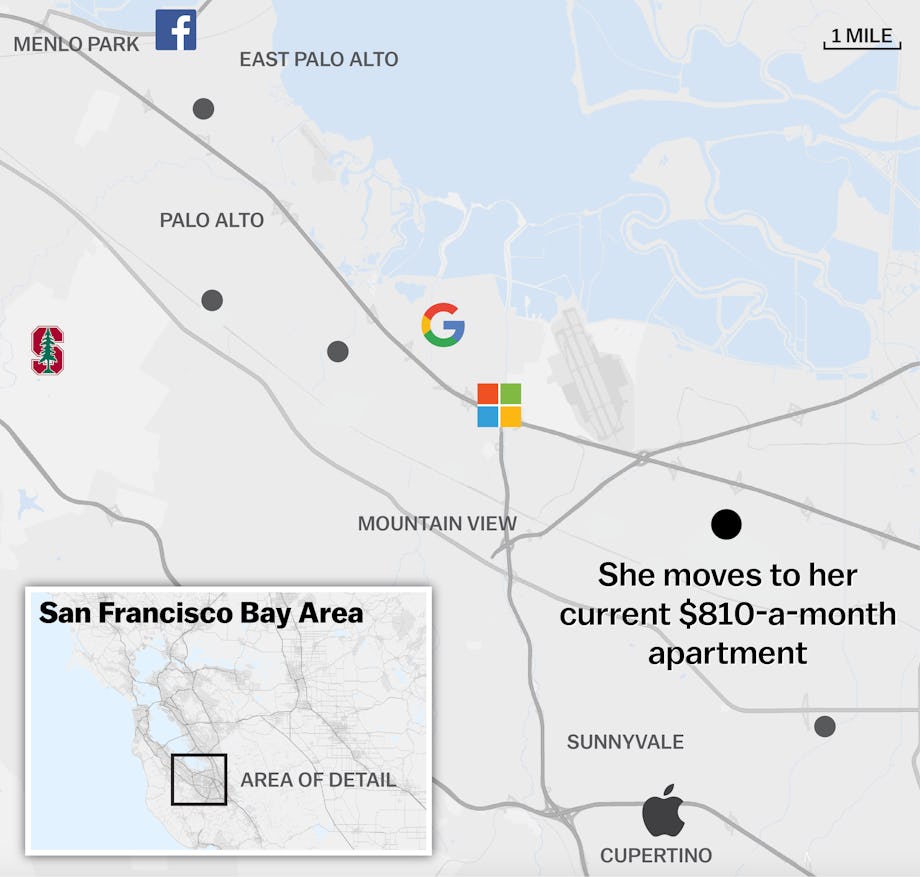

Like many women of her day, Suzan didn’t graduate from college. When she was 24, after her last stay in Switzerland, she moved to Mountain View, the town on Palo Alto’s eastern border that is now home to Google and LinkedIn. She was living off a small trust her family had set up for her when she met James at a barbecue their apartment manager threw to foster neighborliness among his tenants. James had grown up in a sharecropping family in Georgia, moved west during World War II, and was more than 17 years her senior, handsome and gentlemanly. Suzan thought: “I can learn something from him.” They were an interracial couple in the late 1960s, which was unusual, though she says her family didn’t mind. It was also an interclass marriage, and it moved Suzan down the income ladder.

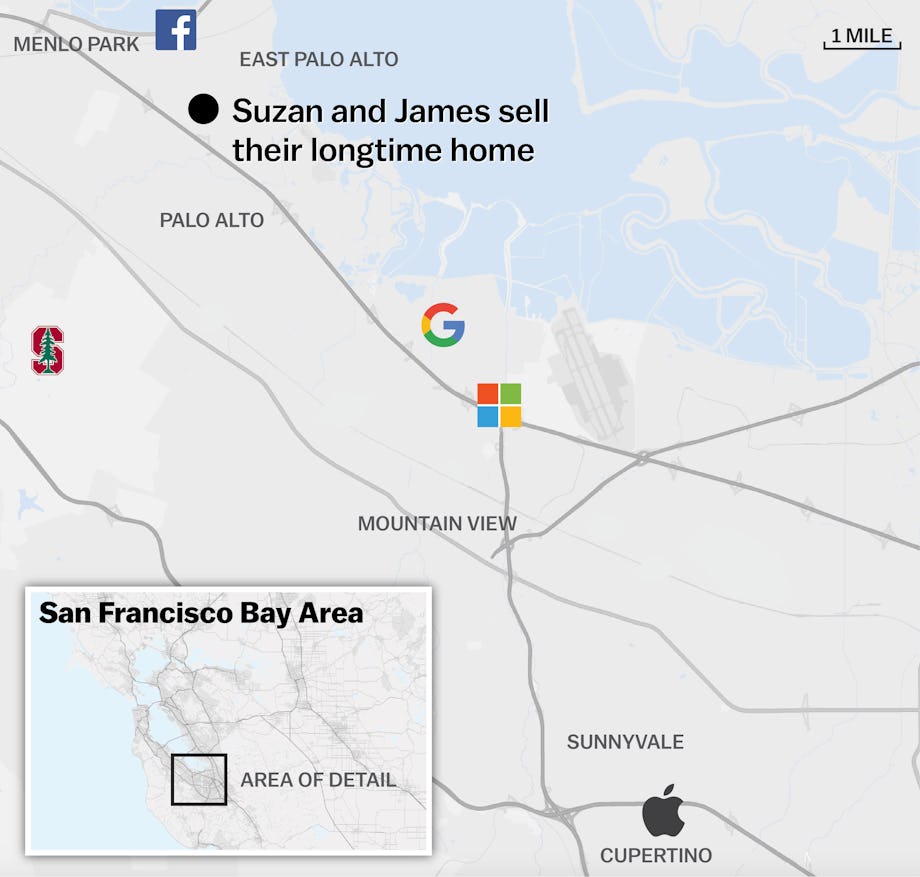

For years, James and Suzan lived together, unmarried. They bought a house on University Avenue, just north of the county line and blocks from downtown Palo Alto, in 1979, and four years later had their only daughter, Nancy. It was the area’s ghetto, and the only source of affordable housing for many years. It was also the center of violence in the region, and, in 1992, was the murder capital of the country.

They never had much money. For most of their marriage, James ran a small recycling company and Suzan acted as his bookkeeper, secretary, and housewife. They refused to apply for most government assistance, even as homeless elders. “My husband and I had never been on welfare or food stamps,” she told me. “Even to this day.”

Suzan’s parents died in 2002 and 2003, and her older sister died in 2009. (“I thank God that they’re gone,” she told me. “They would die if they saw me now.”) It was a hard time for Suzan, who went to care for her dying parents and nearly left James. She felt he’d checked out of the difficulties. In retrospect, she thinks his dementia might already have been setting in; James was already in his seventies. He had taken out a second mortgage on their home, and they couldn’t pay it after he retired. They sold the house at a loss in 2005; it’s now a Century 21 office.

After they moved into the van, they settled into a routine. On the nights before James’s early-morning treatments, they slept in the dialysis center’s parking lot. Otherwise they generally stayed at Cubberley. They were still living off James’s retirement income, but most of it went to the $500 needed to rent the two storage units where their furniture remained, until they lost one for nonpayment. Finally, a few months in, Suzan was able to use a clause in a trust set up by her mother’s father to help her out in an emergency. It doubled their income—much of which was eaten up by the costs of gas, the remaining storage unit, parking tickets, and the other expenses of an unsettled life. It was a respectable income, one that technically kept them above poverty, but it still wasn’t enough for rent.

James was increasingly ill and van life was taking a toll. In addition to James’s other problems, both he and Suzan were starting to experience some of the health problems common among the homeless. The backseat of the van filled with bags of clothes, papers, fast-food detritus, pens, old parking tickets, and receipts. As the junk built up, the recline of their seats inched forever upward, until they were sitting up all the time, causing their legs to swell and nerves to become damaged, the medical consequences of not being able to raise your feet at night.

Gentrification used to be about poor neighborhoods, usually black and brown, underdeveloped and full of decrepit and neglected housing stock, run by the occasional slumlord—often described as “blighted,” though that designation has always been problematic—and how they become converted into wealthier ones, usually through the influx of richer white people and their demand for new services and new construction. It’s a negative process for the people who have to move, but there’s occasionally an element of good, because neglected neighborhoods revive. But what’s happening now in the Bay Area is that people who’ve done nothing wrong—not paid their rent late, violated their lease, or committed any other housing sin—are being forced out to make way. Displacement is reaching into unquestionably vibrant, historic, middle- and working-class neighborhoods, like The Mission in San Francisco, a former center of Chicano power. (The Mission alone has lost 8,000 Latino residents in the past ten years, according to a report from the local Council of Community Housing Organizations and the Mission Economic Development Agency.) And it’s happening to such an extent that the social workers who used to steer people to affordable apartments as far away as Santa Rosa or Sacramento, a two-hour drive, are now telling people to look even farther out. The vehicle dwellers I spoke with said they’d heard of friends living in places like Stockton, once a modest working-class city in the middle of the state, receiving notice-to-vacate letters like the one Suzan and James received.

For the most part, the traits that draw people to Palo Alto—good schools, a charming downtown, nice neighborhoods in which to raise a family, and a short commute to tech jobs—are the very same things that made the residents of Cubberley want to stay, even if it meant living in their car. The destabilizing pressure of a real estate market is also felt by the merely rich, the upper middle class, and the middle class, because the high-end demand of the global elite sets the market prices. “My block has the original owners, a retired schoolteacher and a retired postal worker,” said Hope Nakamura, a legal aid attorney who lives in Palo Alto. “They could never afford to buy anything there now.” Most people told me if they had to sell their homes today they wouldn’t be able to buy again anywhere in the area, which means many Palo Altans have all of their wealth tied up in expensive homes that they can’t access without upending their lives. It makes everyone anxious.

The outcry from the neighbors over Cubberley was so fierce that it reshaped Palo Alto’s city government. The city council is nonpartisan, but a faction emerged that revived an old, slow-growth movement in town, known as the “residentialists.” Their concerns are varied (among them, the perennial suburban concerns of property values and traffic), but their influence has been to block any new development of affordable housing and shoo people like Suzan and James away from Palo Alto. An uproar scuttled an affordable-housing building for senior citizens near many public transit options that had been proposed by the city housing authority and unanimously approved by the city council. Opponents said they were worried about the effect the development would have on the surrounding community—they argued it wasn’t zoned for “density,” which is to say, small apartments—and that traffic congestion in the area would be made worse. Aparna Ananthasubramaniam, then a senior at Stanford, tried to start a women’s-only shelter in rotating churches, modeled after the Hotel de Zink. She said a woman came up to her after a community meeting where the same concerns had been raised by a real estate agent. “Her lips were quivering and she was physically shaking from how angry she was,” Ananthasubramaniam told me. “She was like, ‘You come back to me 20 years from now once you have sunk more than $1 million into an asset, like a house, and you tell me that you’re willing to take a risk like this.”

The trouble for Cubberley began when neighbors went to the police. There’d been at least one fight, and the neighbors complained about trash left around the center. At the time, Cubberley was home to a 64-year-old woman who’d found a $20-an-hour job after nine years of unemployment; a tall, lanky, panhandler from Louisiana who kept informal guard over her and other women at the center; a 63-year-old part-time school crossing guard who cared for his dying mother for 16 years, then lived off the proceeds from the sale of her house until the money ran out; two retired school teachers; a 23-year-old Palo Alto native who stayed with his mother in a rental car after his old car spontaneously combusted; and, for about six months, Suzan and James. “They didn’t fit this image that the powers that be are trying to create about homeless people. They did not fit that image at all,” Suzan told me. “We made sure the premises were respected, because it was an honor to be able to stay there.” She and others told me they cleaned up their areas at the center every morning.

Pressured to find a way to move the residents out, the police department went to the city council claiming they needed a law banning vehicle habitation to address the neighbors’ concerns. Advocates for the homeless said that any problems could be solved if police would just enforce existing laws. Local attorneys warned the city council that such laws could soon be considered unconstitutional, because the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals was hearing a challenge to a similar law in Los Angeles. Carrie LeRoy, an attorney who advocated on behalf of the unhoused, and other attorneys threatened to file a class-action lawsuit if the vehicle-habitation ban ever went into effect. The city council passed the ban anyway, in a 7-2 vote in August 2013, and the police department and other groups in the city started an outreach program to tell people about the law. “All of them had received these notices from the city,” LeRoy said, “And it was basically like, ‘Get out of our town.’”

A few weeks later, the city council also voted to close the showers at Cubberley and give it a 10:30 p.m. curfew, which made it illegal to sleep there. On their last night there, in October 2013, Suzan and James left around 8 p.m. so they wouldn’t get caught past the new curfew. They tried some old haunts and got kicked out. The stress of living in the van was hard on James. Around this time, James decided to end his dialysis. “Of course, we knew what that meant,” Suzan said.

One night, about a month after leaving Cubberley, the police pulled Suzan and James over. Their registration was expired. “This officer, he got a wild hair, and he said, ‘I’m going to impound your car,’ and called the tow truck.” Suzan told me. They got out of the car. Without pushing and demanding, she realized, she was never going to get out of the situation. She told me she said to the officer, “This is our home, and if you impound it we will not have a home.” He insisted. “I said ‘That’s fine. You do that. We will stay right here. I will put the beds out, I will put what we need here, right here on the sidewalk.” Other officers arrived and talked to them. They asked Suzan whether, surely, there was some other place they could go. “I said, ‘We have no place to go, and we’re staying right here.’ I was going to make a stink. They were going to know about it.” Suzan told me people were poking their heads out of their homes, and she realized the bigger fuss she made, the more likely officers might decide just to leave them alone.

Because James’s health had continued to worsen, he and Suzan finally qualified for motel vouchers during the cold weather. They got a room in a rundown hotel. “It had a microwave and a hot bath,” Suzan said. In his last few days, James was given a spot in a hospice in San Jose, and Suzan went with him. “It was so cut-and-dry. They said, ‘This is an end-of-life bed, period,’ ” Suzan said. “And I never said that to James.” He died on February 17, 2014, and a few weeks later a friend of theirs held a memorial service for James at her house. Suzan wore an old silk jacket of her mother’s, one that would later be ruined by moisture in the van, and a necklace Nancy had made. They ate James’s favorite foods—cornbread, shrimp, and pound cake. Suzan had a few motel vouchers left, and afterward stayed with friends and volunteers for a few weeks each, but she felt she was imposing.

That summer, she returned to her van. It was different without James; she realized she’d gotten to know him better during their van life than she ever had before. Maybe it was his dementia, but as they drove around or sat together, squished amidst their stuff, he’d started to tell her long stories, over and over, of his youth in Georgia. She’d never heard the tales before, but she’d started to be able to picture it all. On her own, without his imposing figure beside her, Suzan was scared, and more than a little lonely. Most nights, she stayed tucked away in a church parking lot, without permission from the pastor, hidden between bushes and vans. The law wasn’t being enforced, but sleeping in the lot made her a kind of a criminal. “The neighbors never gave me up,” she said.

Suzan told me she was in a fog of denial after James’s death, but it’s probably what protected her because homelessness is exhausting. “You start to lose it after a while,” she said. “You feel disenfranchised from your own society.” The Downtown Streets Team, a local homeless organization, had been helping her look for a long-term, stable housing solution. Indeed, Suzan told me that at various times, she and James had 27 applications in for affordable housing in Palo Alto. (When he died, she had to start over, submitting new applications for herself.) Her social worker at the local senior citizens center, Emily Farber, decided to also look for a temporary situation that would get Suzan under a roof for a few months, or even a few weeks. “We were dealing with very practical limitations: having a computer, having a stable phone number,” Farber said. Craigslist was only something Suzan had heard of. She’d finally gotten a cell phone through a federal program, but hadn’t quite mastered it.

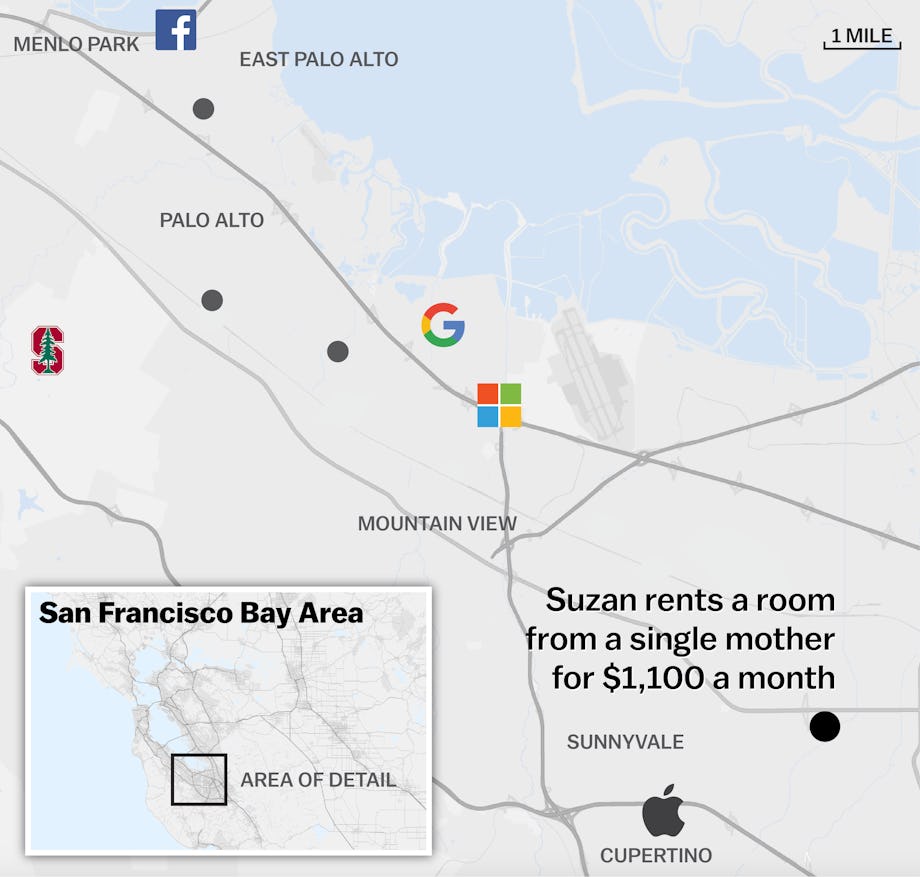

For many months, Farber struck out. She didn’t think Suzan would want to live with three 25-year-old Google employees, or that they’d want her, either. She even tried Airbnb. Because Suzan didn’t have a profile, Farber used her own, and wrote to people who had rooms listed to say her 69-year-old friend needed a place to stay in the area for a couple of weeks. “We got three rejections in a row,” she said. Finally, in November, they found a room available for rent for $1,100—about 80 percent of her income from the trust and her widow’s benefits from Social Security. Suzan would have her own bedroom and bathroom in the two-bedroom apartment of a single mother. The mother crowded into the other bedroom with her 16-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter. The only downside for Suzan was that it was in Santa Clara, another charmingly bland suburban enclave in the South Bay, a half hour south of Palo Alto and a world away for Suzan. “It’s out of my comfort zone, but that’s OK!” she told me.

I met Suzan on the day she moved in, and the concept of being able to close a door was almost as unsettling to her as the concept of sleeping in the van had been. “I’m in this kind of survival mode,” she said, and had found a certain comfort in her van. “I’ve got this little cocoon I’m staying in, and everything is within arm’s reach.” She had a big blue mat in the back of the van, like a grown-up version of the kind kindergartners nap on, but soon she’d acquire a bed. She retrieved her old TV from her storage unit. She made a comfortable room, with chairs and a bed and a small table, and decided to eat her meals in there. She only signed a lease for three months, because it wasn’t really sustainable on her fixed income. She’d also applied for an affordable housing complex being built for seniors in Sunnyvale, one that would provide permanent housing for 60 senior citizens from among the 7,000 homeless people in the county at the time. She’d find out in April if she was selected in the lottery. All her hopes were pinned on it.

In the first few weeks after her move to Santa Clara, Suzan spent a healthy portion of her limited income on gas, driving the Explorer back and forth to Palo Alto. After all, her post office box was there, and so were her social workers. Her errands demanded a lot of face time, and in some ways, she still filled her days the way she had before she got her room, moving around trying to solve her problems. Her car was still packed, too, as if she hadn’t let go of the need to drive in it, to move forward, to keep her stuff around her within arm’s reach, as if she were still without a home base.

Two afternoons a week she went to a Palo Alto food closet. She usually made it right before it closed, in the early afternoons. When her number was called, she went up to the counter to watch the volunteer sort through what was left on the shelves, finding the most recently expired items—these were older goods grocery stores couldn’t keep past their sell-by dates. Suzan’s politeness was, as always, almost formal, from an earlier era, when being ladylike was a learned skill. The volunteer would ask her if she wanted milk, or peaches, or a serving-size Baggie of cereal, and she’d say, “Yes, very much so!” These days, she got to take raw eggs instead of the boiled ones, a treat reserved for those with kitchens. Her requests were glancing rather than direct. “Have you any lettuce?” and the answer was often no. I said it seemed like an efficient operation. Suzan said, “I really know the drill!”

Suzan needed to visit her social worker, Julia Lang, at the Downtown Streets Team office to get the form that allowed her to go to an even better food bank. She asked the receptionist whether her social worker was in. She wasn’t, and Suzan explained she was looking for the food bank vouchers. Then the receptionist asked for her address. That stopped Suzan. The receptionist explained that the pantry was for Palo Alto residents, and Suzan was considering, for the first time, whether that counted her. Suzan explained that she and her husband had gone to the pantry the year before, and said they should be in the system. We waited while the receptionist looked. Suzan waved at someone she’d seen around for years, from her car-dwelling days. Suzan told the receptionist, again, that they really should be in the system. But they weren’t. Suzan said that was OK, and she would come back. The receptionist said, “Are you sure? I just need your ID and your address.” Suzan demurred. She needed to talk to her social worker. This is what it meant to have to leave her hometown. She was leaving the city where she and James had known people, the city where James had died, the city where she’d grown up and near where she’d raised her own daughter. It was the city where she knew where to go, where she’d figured out how to be homeless. It was the city where she knew the drill.

That homelessness persists in Silicon Valley has puzzled me. It has an extremely wealthy population with liberal, altruistic values. Though it has a large homeless population relative to its size, in sheer numbers it’s not as large as New York City’s or L.A.’s. Some of the reasons could be found in the meeting on November 17, 2014, when the city finally overturned the car-camping ban. It had never been enforced because, as predicted, the Ninth Circuit had overturned L.A.’s ban. In the end, all but one person who’d voted for the ban the first time around voted to overturn it. The lone dissenter was councilman Larry Klein. “The social welfare agency in our area is the county, not the city,” he said. “To think we can solve the homeless problem just doesn’t make sense.”

This idea was repeated many times among city officials—that homelessness was too big an issue for the city to resolve. The city of Palo Alto itself has one full-time staff member devoted to homelessness, and it coordinates with county and nonprofit networks to counsel, house, and feed the homeless.

During the fight over the ban, the city tried to devise an alternative—a program that would allow car dwellers to park at churches—but then left the details up to the faith community to work out. Nick Selby, an attorney and member of the Palo Alto Friends Meeting House, said he and his fellow Quakers met with community resistance when they tried to accommodate three or four car dwellers on their tiny lot. Neighbors circulated a petition listing concerns like “the high prevalence of mental illness, drug abuse, and communicable diseases in the homeless population” and the risk of declining property values. But Selby said some of their concerns were fair. “People who objected were saying to the city, ‘What’s your program?’” Selby said. “And the city really had no answer to those questions.” Without a solid plan and logistical help from the city, other churches were reluctant to step forward. “The churches weren’t prepared to deal with this,” he said. After the church car-camping plan fell through, the city council said it had no choice but a ban.

Santa Clara County, too, struggles to address the problem. The county is participating in federal programs to build permanent supportive housing for the chronically homeless population, the population of long-term homeless who typically have interacting mental health and substance abuse problems. But land is expensive here, and the area is shortchanged by the federal formula that disperses funds. California, ever in budget-crisis mode, provides limited state funds. There isn’t a dedicated funding stream from the cities, which don’t necessarily pay a tax to the county for these projects, and local affordable housing developments are often rejected by residents as Palo Alto’s was. In September, the city of San Jose and the county announced a $13 million program to buy old hotels and renovate them as shelters, which will make 585 new beds available. While advocates credit the county’s efforts with cutting the estimated homeless population by 14 percent since 2013, the number of people like Suzan, who hide in their cars, is almost certainly underestimated. But most such efforts are centered in San Jose. Chris Richardson, a director of the Bay Area’s Downtown Streets Team, said what needs to happen is not a mystery: Other cities have to fund affordable housing, they have to fund more of it, and they have to do it in their own neighborhoods, without relying on San Francisco and San Jose to absorb all of the area’s poverty and problems. “You can’t just ship them down to the big, poor city,” he said.

When Palo Alto originally passed the car-camping ban, it also devoted $250,000 to the county’s homelessness program. When they voted to rescind the ban, council members asked for an update on what happened to the money. The city staff was not prepared to report on how it had been spent at that council meeting, more than a year into the funding. Members of the council again reiterated their desire to help the homeless. “Helping the homeless” was tabled, as a general idea, for another agenda at another meeting, as it always seems to be, or passed off to the county, or to someone else—and so helping the homeless is something nobody does.

Through the winter, Suzan remained ill; it was a bad flu season. She kept paying the rent on her room, on her storage units, on her P.O. box in Palo Alto, and she tried setting aside money she owed on parking tickets. Some months she’d run out of gas money to drive the 15 miles to Palo Alto and check her mail or visit her social workers. She was waiting to hear about the affordable apartment.

In May, she was denied. Suzan had bad credit, both because of the unpaid storage unit she and James had lost and because otherwise her credit history was so thin. Julia Lang, one of her social workers, told me she couldn’t even get a credit score for Suzan. Lang said people get denied on credit, or because they make too little for affordable housing that’s supposedly intended for extremely low-income people, all the time. “When you’re that destitute and have gone through so many complicated situations, what are the chances that your credit’s going to be good?” she said.

Suzan was livid and despondent, and she decided to appeal. “I wasn’t going to take that lying down,” Suzan told me. “I was proud of myself.” Catholic Charities helped her appeal. Suzan had to write a letter showing how she intended to repair her credit, and that she understood why it was bad in the first place. During the months of back and forth, Suzan bought a new Jeep, only one year newer than the Explorer, in case she needed to sleep in her car again. In July, she learned she’d won her appeal. She had two weeks to get her affairs in order, pay the first month’s rent and security deposit, and move in. Her social workers helped her with some of the move-in costs, and she signed a lease for a year.

I saw Suzan again in August, about three weeks after she’d moved in. Her hair was trimmed. She was wearing a brightly colored muumuu, blue and green with tropical flowers—“It’s a housedress but you can wear it out on the street!”—and a green sweater tied around her shoulders. She seemed relaxed and rested, and I told her so. Her bed was full of folded clothes, and her room was still in disarray. She was trying to cull her storage unit so that she could get a smaller one and cut down on rent. Most of the people in her complex had been in the same boat as Suzan, or had been worse off. She pays $810 a month, the amount determined to be affordable for her income. It had taken her more than three years, help from at least three social workers, and thousands of dollars, but she was finally stably housed. At least, for a year.