On November 19, 2013, employees of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service discovered the carcass of a large mammal not far from the North Carolina coast. It lay twisted in a bed of twigs, the victim of an apparent gunshot. The government workers recognized its thick gray coat, which turned cinnamon around its slender snout and pointed ears, and the radio collar on its neck. It was a red wolf, an animal that is, by some counts, the most endangered wild canid in the world.

Despite the wolf’s precarious status, the shooting was hardly a surprise. Wolves have always been controversial wherever men have encountered them. Many people remember them as the sinister villains of old-time children’s tales and fear them as a threat to humans, livestock, and pets alike. In North Carolina, residents of the small communities on the Albemarle Peninsula, a tongue of swamp and farmland just before the crowded beaches of the Outer Banks, have been particularly on edge. “How would you feel letting your kids outside to play, knowing there are wolves out there?” Annie Liverman, a waitress at the Columbia Crossing restaurant in Columbia, asked me on a recent visit. Never mind that red wolves have never actually attacked a human. In the farming town of Fairfield, Frances Cuthrell said she leaves Christmas lights on her home year-round, hoping they’ll scare the wolves away. At her convenience store, C and C Groceries, she keeps her pet Chihuahua behind the counter. “I won’t even let her in the yard,” she said. Chip McCann, a local farmer who said he had no quarrel with the animals, put himself squarely in the minority. “To be honest with you, everyone around here hates them,” he said.

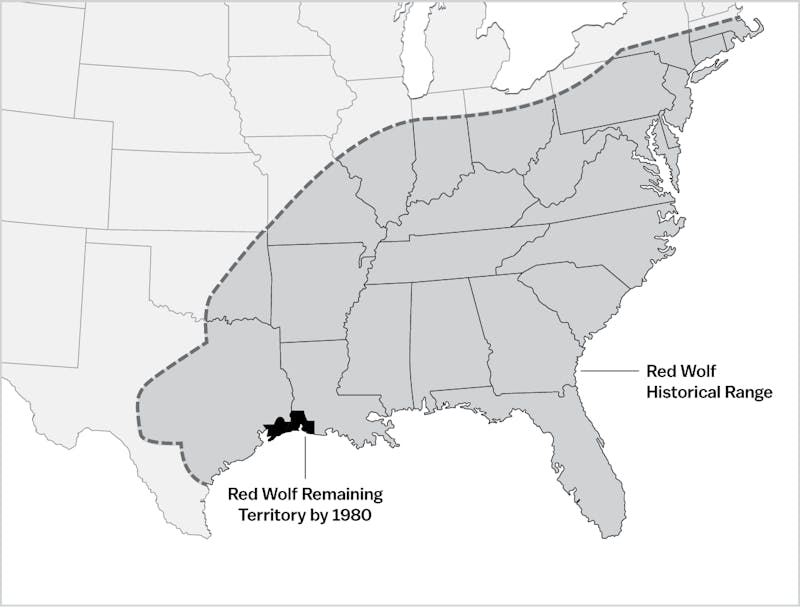

Before European settlement, the red wolf was the dominant predator in the southeastern United States, with a range stretching from Florida to eastern Texas and up to southern Illinois. By 1980, however, humans had persecuted them to the precipice of extinction. In response, the Fish and Wildlife Service launched a bold initiative. It captured the last surviving red wolves from the salt marshes along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas and transported them to a zoo in Tacoma, Washington, where their numbers could grow back in safety. It was the first captive-breeding rescue program in the agency’s history, following Congress’s passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973, and it has served as a model for high-profile programs to save other animals, including the gray wolf in Yellowstone and the California condor.

In 1987, scientists reintroduced four pairs of red wolves into the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge on the North Carolina coast. For days, the animals hung around their enclosures, but eventually they set out to explore, and for the first time in a century, wild wolves inhabited the Atlantic coast. Over the next 20 years, the number of wolves in North Carolina swelled to about 120—a happy outcome, except for the fact that they began to spread beyond the wildlife refuge and onto private land.

It is illegal under federal law to kill a red wolf, given their status as an endangered species. But since the year 2000, shootings have become the number-one cause of death among red wolves, decimating the population. Today, the number of red wolves in North Carolina stands between 50 and 75 animals —half what it was a decade ago. Once again, the red wolf is on the verge of disappearing from the wild.

To environmentalists, the idea of letting the red wolf go extinct is simply unthinkable. But scientific research has complicated their standoff with local hunters and property owners. Since the red wolf was originally classified as an endangered species, biologists have studied it intensely—sequencing its DNA, scrutinizing its morphology, and piecing together its evolutionary history. And they’ve put forward a compelling new theory: The red wolf, an animal the U.S. government has spent decades and millions of dollars attempting to save from extinction, may not actually be a distinct species at all.

The implications of this idea extend far beyond the swamps and farms of North Carolina, threatening the very foundations of biology itself. “Not to have a natural unit such as the species would be to abandon a large part of biology into free fall, all the way from the ecosystem down to the organism,” the noted biologist and theorist E.O. Wilson wrote in his 1992 book The Diversity of Life. And yet, the research into the red wolf challenges our accepted notions about how species are defined—and about how evolution actually works.

Since the eighteenth century, the animal kingdom has been classified according to the binomial naming system of the Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus. As the biologist Ernst Mayr wrote, Linnaeus believed that every species was “the product of a separate act of creation and was therefore clearly separated from all other species.” The red wolf, or Canis rufus, was first classified in 1851 by John James Audubon, who observed in them the “same sneaking, cowardly, yet ferocious disposition” he believed that all wolves shared. Audubon identified the red wolf as a subspecies of the gray wolf ( Canis lupus), but Stanley P. Young and Edward A. Goldman solidified the idea of it as a distinct species in their classic 1944 study The Wolves of North America. They noted, however, that the red wolf, especially in Oklahoma and Texas, “is so small and in general character agrees so closely with C. latrans [the coyote], which it overlaps in geographic range, that some specimens are difficult to determine.” They acknowledged “the possibility of hybridism in some localities,” but didn’t view it as a factor in the animal’s evolution. Men could breed hybrid animals, like the mule (a cross between a female horse and a male donkey), but hybrids were thought to be freak occurrences in the wild. Evolution, the thinking went, was the slow process of sorting species out, while hybridization blended species back together. In his 1970 book The Wolf, the biologist L. David Mech suggested that “the red wolf may be a fertile wolf-coyote cross.” He based his theory on the red wolf’s morphology—it was larger than a coyote but smaller than a gray wolf; it looked like a mix between the two. But Mech’s idea failed to gain traction at the time.

A New Theory of Evolution

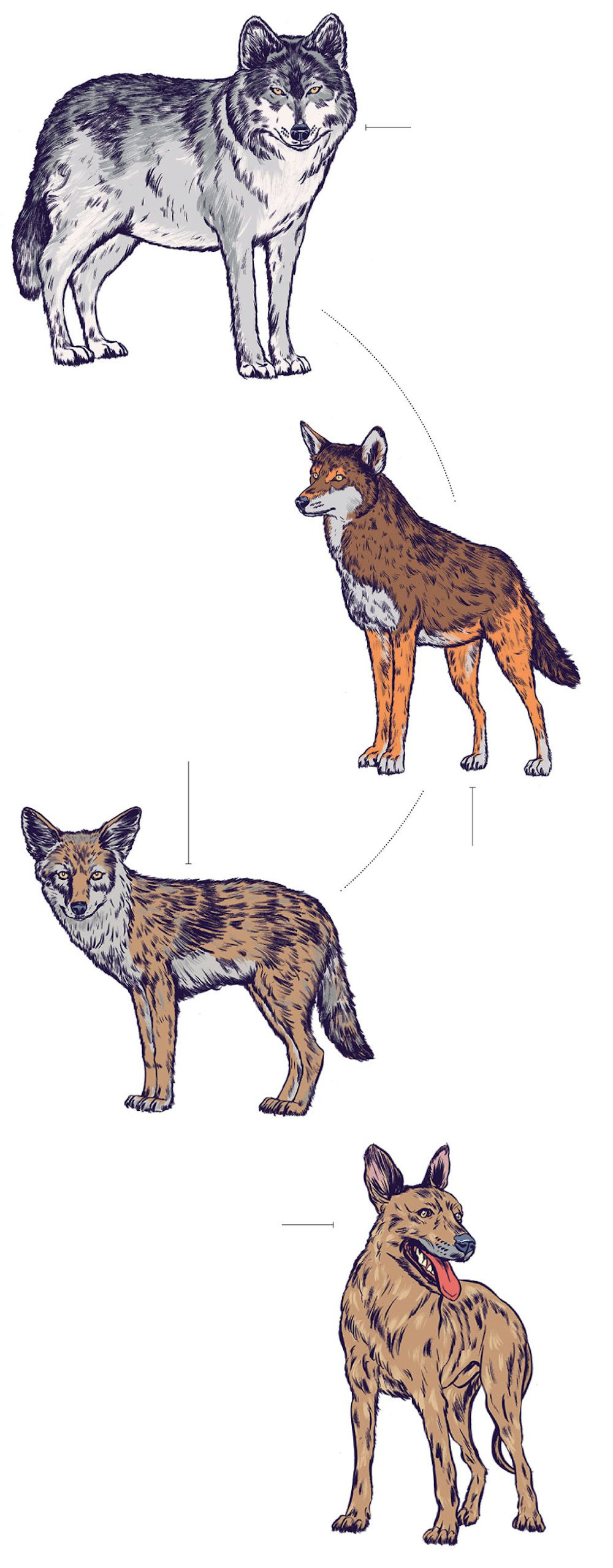

Gray wolves, red wolves, coyotes, and dogs all descended from a common ancestor that prowled the Earth one to two million years ago. But recent scientific evidence has upended the traditional “tree of life” model of evolution and proposed a more complicated web.

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Gray wolves are believed to have crossed into North America between 300,000 and 750,000 years ago.

COYOTE

Canis latrans

Unlike gray wolves, coyotes evolved in North America. Nevertheless the two species are closely related and have successfully reproduced in captivity.

Red Wolf

Canis rufus

Scientists have debated whether the red wolf is descended from gray wolves or coyotes—or, most provocatively, is a hybrid of the two.

Domesticated Dog

Canis lupus familiaris

Dogs are still so closely related to gray wolves that they’re classified as a subspecies. Domestication is believed to have taken place between 15,000 and 40,000 years ago.

Most biologists believed that hybridization in nature primarily

resulted from human interference, when people remove a barrier between two

closely related species, leading to a “hybrid swarm” that obliterates the

distinctiveness of one or both types of animal. This process seemed to be under

way by the middle of the twentieth century in the salt marshes of western

Louisiana and eastern Texas, where local ranchers relished the opportunity to

shoot red wolves and string the carcasses from their fences. The disappearance

of wolves from the American landscape had opened the door for coyotes—small,

solitary, and crafty animals better adapted to life alongside humans—to spread

eastward into the wolves’ former range. In the salt marshes, the coyotes

encountered the last surviving red wolves, whose numbers were so depleted that

they took the coyotes as their mates. Thus, they diluted their own gene pool

with each new hybrid generation. In 1974, the nature writer Edward Hoagland

visited the area and found just a few “sorry smaller specimens” of red wolf—sickly,

pathetic creatures that bore little resemblance to the fearsome predators he

had expected and that seemed doomed to extinction. “It soon seemed to me,”

Hoagland wrote, “there may be no hope.”

When the Fish and Wildlife Service decided to save the red wolf, its first challenge was to separate the wolves from the coyotes. Genetic testing was primitive and impractical, so the agency relied instead on morphology. It trapped some 400 animals, weighed each of them, compared their howls, and measured their skulls using X-rays. It then compared the cranial measurements with red wolf skulls from the 1940s, a time before hybridization with coyotes was believed to have started. In the end, it identified just 14 animals as true red wolves. The animals were transferred to Point Defiance Zoo in Tacoma, and the red wolf was declared extinct in the wild.

“The red wolf had always been a puzzle,” Robert Wayne, a biologist at UCLA, told me. In 1991, he and a team of researchers set out to decipher the red wolf’s origins. At that time, some scientists believed the red wolf was more closely related to the coyote, while others believed it was more like the gray wolf. But the only available evidence was a handful of fossils and historical records. Few scientists had ever worked with living red wolves. Wayne and his team wanted to settle the question of the red wolf’s origins once and for all. “I was hoping to be the first person to sequence DNA from a red wolf,” said Susan Jenks, a biologist at Russell Sage College who co-authored the analysis.

Wayne and Jenks started with blood samples from red wolves living in captivity in American zoos, focusing on 4 percent of the genome. When they sequenced the DNA, however, they were mystified. Every section of red wolf DNA matched almost exactly with the equivalent section of DNA from two other animals: the gray wolf and the coyote. They found no part of the red wolf’s genome that was unique. “I kept running the analyses and checking and double-checking for contamination,” Jenks said. The conclusion, however, was inescapable. “Finally it occurred to me it would make sense that they’re hybrids,” Jenks said.

Morphological measurements had long been one of the traditional methods of taxonomy. But Wayne and Jenks argued that, in the case of the red wolf, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s analysis had been unreliable. After testing the DNA of red wolves living in zoos, they examined old samples from wild wolves as well. They looked at 77 blood samples taken from wild canids in Texas and Louisiana between 1974 and 1976, shortly before the red wolves’ rescue. Each sample had been classified as red wolf, coyote, or hybrid based on morphological criteria. When Wayne and Jenks analyzed the DNA, however, their initial findings were confirmed. The majority of wild red wolf samples had coyote genotypes, while the rest had gray wolf genotypes. Once again, Wayne and Jenks found no unique red wolf DNA.

Their conclusion called into question the U.S. government’s methodology for choosing red wolves to be whisked off to the zoo in Tacoma. “To me it looked kind of like an experiment in selective breeding,” Wayne said. “You have some idea in your mind what a species should look like, and you pick individuals that you think look like that ideal.”

Moreover, their study upended the conventional thinking about how we classify species altogether. Hybridization with coyotes had threatened to wipe red wolves from the planet—or so scientists had believed. Now, however, Wayne and Jenks’s DNA analysis had given Mech’s radical idea new life: Hybridization had, it seemed, put red wolves on the planet in the first place. “The Endangered Species Act embodies very typological thinking—there are these discrete entities out there and they should be preserved separately in isolation,” Wayne said. His and Jenks’s study suggested that wild animals had little regard for the categories men had assigned them.

Where, then, did red wolves come from? Wayne theorized that gray wolves had once inhabited the eastern U.S. and began to hybridize with coyotes as settlers pushed these populations westward. The Fish and Wildlife Service resisted the theory of a hybrid red wolf origin, though. It was hard to square Wayne and Jenks’s paper with the fossil and historical records that had always guided studies of the animal. No one had ever observed a gray wolf and a coyote cross in the field, for instance (although they had reproduced in captivity). Nor was there much fossil evidence that gray wolves or coyotes had lived in the eastern U.S. prior to the twentieth century. “There were no gray wolves and there were no coyotes in the Southeast any time from 10,000 years ago to 100 years ago,” said Ronald Nowak, a field biologist whose early studies of the red wolf had been crucial in rescuing the animal. In 2002, he published an exhaustive review of the fossil record and reiterated his belief that the gray wolf and red wolf were very closely related but distinct.

On the ground in North Carolina, too, researchers working with the

Red Wolf Recovery Program reported that red wolves, regardless of their

origins, were exhibiting unique behaviors, like pack hunting, and that they

preferred each other to coyotes as mates. “We found certain things about their

behavior and their morphology that would lead to the conclusion that they are a

distinct species, something that’s unique that’s not being achieved by other

species on the landscape,” said Joseph Hinton, a postdoctoral researcher at the

University of Georgia who studied the relationship between red wolves and

coyotes for his dissertation.

Even so, the Fish and Wildlife Service acknowledged that its efforts to distinguish red wolves from coyotes based on their physical traits was something less than a perfect science. “We knew that by taking this approach, we might be creating a new species of red wolf that was different than the species had been originally,” Curtis Carley, the original project leader of the Red Wolf Recovery Program, told Jan DeBlieu in her 1993 book Meant to Be Wild. “But under the circumstances, we felt we really had no choice.” It seemed like a practical risk to take: better to preserve a species in a less-than-pure form than let it die out altogether.

Since Wayne and Jenks published their original findings, other researchers have taken a renewed interest in the red wolf. In 2000, a group of scientists from Trent University in Canada pushed back against Wayne and Jenks’s theory with their own DNA analysis. They proposed that the red wolf was closely related to the eastern Algonquin wolf, another midsize wolf in the Great Lakes region of Canada, which had diverged from coyotes 150,000 to 300,000 years ago. According to this theory, Algonquin and red wolves evolved to catch deer in Eastern forests, while coyotes evolved to catch rodents and other small prey out West. They found scant evidence of direct gray wolf-coyote hybridization, said Paul Wilson, one of the authors of the study.

The Trent team expanded its theory in subsequent studies, and Wayne responded with another analysis in 2011, this time looking at 48,000 DNA markers —the largest data set to date. Once again, he and his team found no unique red wolf DNA. Wayne’s team has now sequenced the entire canid genome and will soon publish their results. “We actually think there may be some unique aspects of the genome of red wolves that come from gray wolves that used to inhabit the American Southeast,” he said. But the results still point toward a hybrid origin. “They’re not what the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wants to hear,” Wayne said.

What to do, then, about the red wolf? The Fish and Wildlife Service has never really known how to treat hybrids. In the case of the Florida panther it actually encouraged crossbreeding with a related subspecies, in order to reduce inbreeding and introduce new genetic variety into a tiny population. But in the case of another critically endangered animal, the dusky seaside sparrow, it refused to authorize “genetic rescue” through crossbreeding with a related subspecies in the 1980s. A few years later, the dusky seaside sparrow went extinct.

The Interior Department, charged with enforcing the Endangered Species Act, has reversed the government’s position several times over the years as to whether the law protects hybrids. Initially, the government adopted a general policy to “discourage conservation efforts for hybrids,” under the common notion that hybridization destroys species instead of creating them. Then, in 1990 Interior determined that “rigid standards should be revisited, because the issue of hybrids is more properly a biological issue than a legal one.”

After their initial finding, Wayne and Jenks recommended continued protection for the red wolf under the Endangered Species Act. “Even if the red wolf is entirely a hybrid, it filled the role as top predator throughout its former geographic range and was thus an integral part of the ecosystem,” they wrote in their original paper. Others, however, have urged the federal government to pull the plug.

“Wayne and Jenks’s results on the red wolf suggest that here no species is being saved (and certainly nothing of great taxonomic distinctness),” John Gittleman and Stuart Pimm, two zoologists at the University of Knoxville, wrote in Nature in 1991. It’s a view that has taken root in North Carolina, given the recent battles between conservationists and landowners. In 2015, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, which regulates hunting in the state, passed a resolution noting that the “purity of the red wolf genome is questionable” and asked the Fish and Wildlife Service to “declare in federal rules that the red wolf is extinct in the wild in North Carolina.”

The idea of a species may be fundamental to biology; but science offers no precise definition of what a species actually is. Anyone can recognize a black bear and a cardinal as distinct animals, but what about two minnows scooped from separate ponds? For centuries, taxonomists delineated species based on morphology, ecology, and behavior, but there was never any standard method to their classifications. Some taxonomists lumped different populations together based on general similarities, while others split them apart based on minor variances. A taxonomist named C. Hart Merriam working in the United States in the 1880s insisted that there were at least 86 species of grizzly bear in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

“I look at the term species as one arbitrarily given for the sake of convenience to a set of individuals closely resembling each other,” Charles Darwin wrote in The Origin of Species in 1859. Nevertheless, his theory of evolution helped biologists in the twentieth century land on what seemed like a firmer definition: A species was not simply a group of animals that looked alike, but rather a population whose members could reproduce only with each other. This was called the “biological species” concept. Over time, the thinking went, populations became divided by geographical or other barriers and evolved separately from each other, never to reunite. “The origin of species is therefore simply the evolution of some difference—any difference at all—that prevents the production of fertile hybrids between populations under natural conditions,” Wilson wrote.

There were always problems with that definition, though. For one thing, it did not account for asexual reproduction. And plant biologists have long recognized hybridization as an important element of floral evolution. In the 1950s, waterfowl biologists observed crossbreeding between different varieties of North American duck. It was not until biologists gained the ability to examine animals’ DNA in the 1980s, though, that they began to discover that species do not always fit the categories that men have drawn around them. “The process of admixture seems to some people obscene or improper, but actually there are hundreds of hybrid zones known in vertebrates,” Wayne said. The red wolf was not, perhaps, the perfect poster child of an endangered species, but it was a window into the way evolution operates.

As genetic testing has become more common, biologists have found increasing evidence of hybridization among distinct species. Bobcat and lynx are hybridizing in Canada. The clymene dolphin is entirely a hybrid of two other dolphin species. Scientists have theorized that climate change may be the cause of some hybridization, as animals migrate outside of their traditional ranges and encounter new species. The “pizzly bear,” for example, is a cross between a polar bear and a grizzly bear. But the polar bear and grizzly bear genomes show that the two species have exchanged genes throughout history. So have grizzly bears and black bears. Even human beings aren’t quite as distinct as we once thought. The genomes of European and East Asian peoples contain genetic material from long-extinct Neanderthals, indicating that hybridization has played a role in our own development as Homo sapiens.

Evolution had always been represented as a “tree of life,” with animals diverging from each other until each species slotted into a terminal bud. In recent years, however, scientists have begun to adopt a more dynamic view of what constitutes a species. In 2011, Frank Rheindt and Scott Edwards, two researchers at Harvard, published a paper about hybridization in the scientific journal The Auk. They argued that “introgression”—the scientific term for when genes of one species enter the genome of another species through hybridization—had long been “underappreciated” and was, in fact, an “important and pervasive mechanism” in evolution. It allowed for the rapid introduction of “advantageous novelty” into a species’ gene pool. For example, the Neanderthal genes in the human genome affect the outer skin cells that produce hair, which researchers have suggested might have helped Homo sapiens adapt to colder climates when they migrated out of Africa some 60,000 years ago. Another research paper indicated that Tibetans gained the genes that help them breathe at high altitudes from the Denisovans, another ancient and extinct member of the Homo genus.

It is possible, certainly, for distinctive forms to be lost through hybridization. Non-native rainbow trout, for instance, have overwhelmed some of their idiosyncratic relatives in Western streams. But it is also possible for new forms to arise. No animal has demonstrated the rapid evolutionary advantages of hybridization better than the coyote. The coyote was native to the Great Plains but pushed eastward in the twentieth century into wolves’ former range along a front from Texas to southern Canada. The expansion, however, was not in lockstep. The coyotes that spread via Canada colonized new territory at a rate five times faster than their southern counterparts. A research team at the New York State Museum in Albany found that the northern coyotes encountered and hybridized with Algonquin wolves in Canada, producing larger offspring that could more easily hunt deer in Northeastern forests. These hybrid “coywolves” then spread into New York and Maine, states that had lacked wild canids since the nineteenth century. Evolution, a process that typically took thousands of years, had created a new form in a matter of decades. Hybridization held the key.

The coyotes that spread more slowly along the southern route did not encounter wolves—not, anyway, until they reached North Carolina’s Albemarle Peninsula. The Fish and Wildlife Service had chosen to reintroduce red wolves into the wild there in large part because it was coyote-free. But by the 1990s coyotes had reached the Atlantic Coast. The agency detected the first red wolf-coyote hybridization in 1993. In 2000, it declared that hybridization with coyotes was once again the greatest threat to the red wolf’s survival.

At first, the Fish and Wildlife Service trapped and removed the coyotes, but it couldn’t stem the invasion. Then it experimented with a different method. Both red wolves and coyotes are territorial, so the government began to sterilize coyotes rather than remove them. The infertile coyotes couldn’t breed with red wolves, but they defended their territory from fertile competitors, thus creating a buffer around the red wolves. It was an intensive and costly project, requiring a big portion of the program’s $1 million annual budget, but it worked—at least for a while.

Then, in July 2013, North Carolina authorized the hunting of coyotes at night. The Fish and Wildlife Service had managed to keep the coyotes at bay, but now the wolves were once again threatened by hunters, many of whom couldn’t tell the animals apart. This was a point environmental groups highlighted that fall when they sued the state, seeking to ban coyote hunting in the five counties where the red wolf roamed. “It is practically impossible for an untrained person evaluating these species in the field, at night, presumably at a distance, to definitively identify either species,” Michael Chamberlain, an ecology professor at the University of Georgia, testified in the case. In May 2014, a federal judge sided with the environmental groups and imposed a preliminary injunction banning coyote hunting in the red wolf recovery area. “There is a reasonable certainty of imminent harm, killing, or wounding of red wolves,” Judge Terrence Boyle wrote in his decision.

Local landowners and hunters were furious, and many of them seized on the research calling into question the red wolf’s status as a species. They fumed about the lawsuit on internet message boards, where they called the Red Wolf Recovery Program an “obscene disaster” and an “experiment gone horribly wrong.” The most vocal poster, a landowner named Jett Ferebee, complained that the wolves had chased the deer and rabbits off his property. He called red wolves “genetically engineered super coyotes” that the Fish and Wildlife Service “needed to invent [and] hired a zoo in Washington State to construct.” (He declined to comment to the New Republic.) After the judge temporarily banned coyote hunting altogether, the message boards lit up again. On Facebook, Ted Nugent called for Fish and Wildlife employees to be “convicted of their entrenched fraud, deceit & anti-hunting agenda.”

In October 2014, the environmental groups reached a settlement with the state to lift the ban on coyote hunting. Under the agreement, North Carolina would educate the public about red wolves, list the red wolf as a threatened species under state law, and require permits for coyote hunting in the red wolf recovery area. But by then, the Fish and Wildlife Service (which also declined to comment to the New

Republic) had already instituted a review of the Red Wolf Recovery Program to determine whether to continue it at all. The agency promised an answer in the first three months of 2015, then went silent. In late June, it announced that it would need until 2016 to decide the red wolf’s fate. At the announcement of the delay, one journalist asked whether the U.S. government might let red wolves go extinct again in the wild. It’s “one of many possibilities,” the answer came back.

The government has spent tens of millions of dollars on the red wolf, but it is clear now that the population will never grow large enough to remove the animal from the Endangered Species list. “To the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Endangered Species list is a to-do list, something to be checked off,” said Ronald Nowak. “They don’t recognize that there are some species that will just never be non-endangered.”

To some biologists, the red wolf demonstrates how wrongheaded it is for the Fish and Wildlife Service to organize its conservation efforts around species in the first place, given how fuzzy the concept has proven. “I think it’s nonsensical for us to argue conservation-management practices on the basis of genomes that haven’t been impacted by genes from other species,” said Michael Arnold, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Georgia. “If we do that ... then there won’t be anything conserved.”

Instead, Arnold suggested a whole new paradigm for the natural world: not a “tree of life,” with its ever-multiplying and distinct branches, but a “web of life,” with species continually diverging and recombining over time —a truer picture of what actually happens in nature. He proposed that rather than spending conservation money to preserve what we have defined as a species, the U.S. government should buy up tracts of land and let natural evolutionary processes—including hybridization—run their course.

Scientists had hoped that DNA testing would yield clear definitions for animal species. Instead, it’s revealed just how impossible such precise determinations are. And yet few would suggest jettisoning the concept of a species altogether: It is, as E.O. Wilson wrote, too fundamental to human ideas of nature. The difference would be recognizing that a species is a human construction rather than a biological reality—a shift in perspective that would, if anything, give conservationists more flexibility to pursue their goals. “The Endangered Species Act is tied to typology, where it should be more oriented toward process,” Wayne said.

In this view, the red wolf need not be a paragon of genetic purity in order to deserve protection; it need only fill a niche in its ecosystem that no other animal does. Jenks echoed this point as well. “It should be about what an animal does in its habitat, and preserving that habitat, that ecology,” she said.

What that would mean for conservation efforts on the ground in North Carolina remains unclear. For the Fish and Wildlife Service, rescuing the red wolf from extinction is one of its greatest accomplishments. But as the agency continues to deliberate about the future of the recovery program, it has also signaled that it doesn’t have much heart left in the red wolf fight. This summer, a female red wolf wandered onto a landowner’s property in Hyde County. Typically, Fish and Wildlife employees trapped and removed unwanted red wolves from private property, but the wolves often journeyed back, and fed-up landowners have started to deny the agency access to their land. Rather than skirmish with another angry resident, the agency capitulated. It gave the man permission to shoot and kill the red wolf—a decision that drew the ire of environmental groups, who launched a lawsuit against the agency. On June 17, the man picked up a gun and, for the first time since the 1960s, intentionally took aim at and lawfully killed the red wolf. When he handed the corpse over to the Fish and Wildlife Service, they discovered that the wolf was nursing. Her pups would not survive without her care.